"I was now in a wild valley - enormous hills on my right. The road was good, and above it was a causeway for foot passengers. A Welsh harper stationed in the passage played his instrument 'Codiad ur ehedydd.' "Of a surety," said I, "I am in Wales!"

In the mid-1850s, Romantic poet John Clare hitched his poetic mind to his walking foot and gave us a poignant collection of walking poems about England's enclosed farmlands. Around the same time, Henry David Thoreau did equally in America with his celebratory paean to walking, and Anna Atkins continued to publish her revolutionary botany photographs collected during sea and country-side jaunts. For many who would discover their immediate world, the foot-paced journey was the way to do it (at least before the abrupt arrival of the expedient railroad.)

Summit of Bannau Sir Gaer, Bannau Brycheiniog, Wales. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.

Summit of Bannau Sir Gaer, Bannau Brycheiniog, Wales. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.At the same time, a failed lawyer, gifted philologist, and casual Bible salesman named George Borrow (July 5, 1803 – July 26, 1881) decided that rather than travel to continental Europe with his young bride (or other "fashionable" places) he would walk the dragon's spine into Wales (Cymru) and write up the experience "into a little account." Borrow published Wild Wales in 1862. It is a celebration of a unique, ancient land and people.

In the summer of 1854 myself, wife, and daughter determined upon going into Wales, to pass a few months there. We are a country people of a corner of East Anglia, we had become tired of the objects around us and conceived that we should be all the better for changing the scene. I purposed Wales from the first, by my wife and daughter, who have always hankered what is fashionable, said they thought it would be more advisable to go to Harrowgate, or Leamington. I told them there was nothing I so much hated as fashionable life... My knowledge of Welsh, such as it was, made me desirous that we should go to Wales.

Borrow, born in East Anglia, had studied Welsh casually but sufficiently through his father's army colleague. He knew a great deal about Welsh history, language, and literature, not from school (most would have only taught Classical literature) but from personal study. Borrow was a keen traveler and his eagerness to learn was only eclipsed by his desire to demonstrate what he already knew.

Usk Reservoir, on the boundary of Carmarthenshire and Powys, Wales. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.

Usk Reservoir, on the boundary of Carmarthenshire and Powys, Wales. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.The Borrow family settled in a "nice, old-fashioned" inn near Llangollen in the northern mountains, close to the English border.

The northern side of the vale of Llangollen is formed by certain enormous rocks called the Eglwysig rocks, which extend from east to west, a distance of about two miles. The southern side is formed by Berwyn Hills. The valley is intersected by the River Dee, the origin of which is a deep lake near Bala, about twenty miles to the west. Between the Dee and the Eglwysig rises a lofty hill, on the top of which are the ruins of Dinas Brân, which bear no slight resemblance to a crown. The upper part of the hill is bare with the exception of what is covered by the ruins; on the lower part there are inclosures and trees with, here or there, a grove or a farmhouse.

Wild Wales is a close-observed account of an extraordinary country and its people, with section titles like "Fairy-looking Place, the Yew-Tree, the Bridge of Twrch, and a Bitter Methodist." It has drama, gossip, social judgment, and a forthright intake of the vivid scenery. "But it is not for the scenery alone"... that is, Borrow is not a nature writer but a social anthropologist. His most patient and respectful observations are of Welsh homesteads and the contextual history of the buildings and communities.

I proceeded briskly on my way, and in a little time saw a range of white buildings. A kind of farm-yard was before them. A respectable-looking woman stood in the yard. I went up to her and inquired the name of the place.

"These houses, sir," said she, "are called Tai Hirion Mignaint. Look over that door and you will see T. H. which letters stand for Tai Hirion. Mignaint is the name of the place where they stand."

I looked, and upon a stone which formed the lintel of the middlemost door I read "T. H 1630." The words Tai Hirion it will be as well to say signify the long houses. I looked long and steadfastly at the inscription, my mind full of thoughts of the past.

"Many a year has rolled by since these houses were built," said I, as I sat down on a stepping-stone.

"Many indeed, sir," said the woman, "and many a strange thing has happened."

"Did you ever hear of one Oliver Cromwell?" said I.

"Oh, yes, sir, and of King Charles too. The men of both have been in this yard and have baited their horses; aye, and have mounted their horses from the stone on which you sit."

"I suppose they were hardly here together?" said I. "No, no, sir," said the woman, "they were bloody enemies, and could never set their horses together."

"Are these long houses," said I, "inhabited by different families?"

"Only by one, sir, they make now one farm-house."

"Are you the mistress of it," said I. "I am, sir, and my husband is the master. Can I bring you anything, sir?"

"Some water," said I, "for I am thirsty, though I drank under the old bridge." She brought me a basin of delicious milk and water.

And this distilled moment of kindness:

I entered the house, and the kitchen, parlour, or whatever it was, a nice little room with a slate floor. They made me sit down at a table by the window, which was already laid for a meal. There was a clean cloth upon it, a tea-pot, cups and saucers, a large plate of bread-and-butter, and a plate, on which were a few very thin slices of brown, watery cheese.

My good friends took their seats, the wife poured out tea for the stranger and her husband, helped us both to bread-and-butter and the watery cheese, and then took care of herself. Before, however, I could taste the tea, the wife, seeming to recollect herself, started up, and hurrying to a cupboard, produced a basin full of snow-white lump sugar, and taking the spoon out of my hand, placed two of the largest lumps in my cup, though she helped neither her husband nor herself; the sugar-basin being probably only kept for grand occasions.

My eyes filled with tears; for in the whole course of my life, I had never experienced so much genuine hospitality. Honour to the miller of Mona and his wife; and honour to the kind hospitable Celts in general! How different is the reception of this despised race of the wandering stranger. However, I am a Saxon myself, and the Saxons have no doubt their virtues; a pity that they should be all uncouth and ungracious ones!

As hinted by the above passage, Borrow intended Wild Wales for Englishmen, most of whom had never been to Wales, did not travel around the Isles, and were thus earmarked by Borrow for a bit of a literary and moral walloping.

Western Wales. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.

Western Wales. Photograph by Ellen Vrana."This is as it should be," I said to myself; "I now feel I am in Wales." I was now in a wild valley - enormous hills were on my right. The road was good, and above it was a causeway intended for foot passengers. A Welsh harper stationed in the passage played upon his instrument 'Codiad ur ehedydd.' "Of a surety," said I, "I am in Wales!"

Observations taken through time become artifacts, and history becomes what is written on the margins of what happened. Borrow's snapshot of the Welsh, how they lived and worked, and what he perceived they knew and felt about their own lives becomes what we know ourselves.

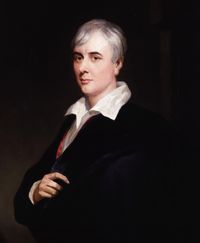

Portrait of George Borrow in 1843, by Henry Wyndham Phillips. Learn more.

Portrait of George Borrow in 1843, by Henry Wyndham Phillips. Learn more.But it is a traveler's diary and observations and belies the complexity of place. Therefore, I temper Borrow's anecdotes with the words of an actual Welshwoman, Jan Morris - a celebrated travel writer who knew something about the complex fusion of people and place and what it meant to be Welsh.

From Morris' diary, written when she was 93:

For seventy years I have lived within the bounds of an ancient Welsh estate, long ago known as a Township, and recorded in 1352 as being inhabited by Einion ap Gruffydd and Lleuci, the daughter of Ieuan. You can't get much more Welsh than that, and with brief intermissions, the district has remained absolutely Welsh ever since - farmed by Welsh families and profoundly impregnated, one might say, with Cymreictod, the intangible state of being that is Welshness. Well, a few years ago a cottage not far away fell vacant. Not being rich I failed to buy it, and so probably for the first time since the days of Einion ap Gruffydd it became inhabited by Sais, Saxons - not Welsh at all, but English people! They were nice people, polite and unobtrusive, but they were English people, and they rebuilt and developed that cottage in an English way... The old magic of the place, the ancient inheritance of Eimion and Lleuci, is abruptly switched off.

From Jan Morris' Thinking Again

With her carefully measured grace, Morris reflects a thought about the nature of Wales as an entity wholly unto itself, an entity that met Borrow with enthusiasm. Still, I cannot help but wonder, were they also happy to see the back of him, Anglican as he was?