“That I should go looking through books for fairy-tale heroines is a wish to validate my claim to a fair share of the future by staking my claim to my share of the past.”

"There is pleasure in out-of-the-way erudition", wrote Borges in his bestiary of fantastic, mythical and fairy creatures. Borges wrote and rewrote the collection and published it many times, each edition more robust than the last. Pleasure is the same word Angela Carter (May 7, 1940 – February 16, 1992) uses in introducing her collection of fairy tales with female heroines: "This is a collection of old-wives tales, put together with the intention of giving pleasure..."

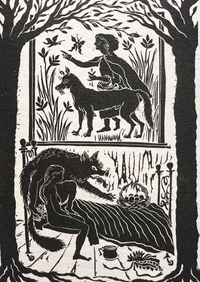

For this Book of Fairy Tales, which she finished weeks before her death, Carter drew on her lifelong knowledge of and passion for fairy tales. It was illustrated by Carter's good friend and student Corina Sargood, whose thick woodcut prints perfectly complement the bold characters.

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood, Carter's life-long friend and pupil. Sargood illustrated the original Book of Fairy Tales and still works as an artist in southeast England.

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood, Carter's life-long friend and pupil. Sargood illustrated the original Book of Fairy Tales and still works as an artist in southeast England.Carter devoted her writing career to giving voice and embodiment to those unjustly diminished by gender, and is straightforward why she featured tales with leading women.

That I and many other women should go looking through books for fairy-tale heroines is a version of the same process, a wish to validate my claim to a fair share of the future by staking my claim to my share of the past.

Besides being included in this collection, which introduces Carter as the storyteller, the actual stories are unchanged (as much as oral stories can be).

I've tried, as far as possible, to avoid stories that have been conspicuously 'improved' by collectors or rendered 'literary', and I haven't rewritten any myself, however great the temptation, or collated two versions, or even cut anything, because I wanted to keep a sense of many different voices. Of course, the personality of the collector or the translator is bound to obtrude itself, often in unconscious ways, and the editor's personality, too.

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood.

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood.Carter instinctively avoids nominal divisions like time or geography, instead collating the tales under categories like 'Strong Minds and Low Cunning,' 'Sillies,' and 'Unhappy Families.' My favourite selection is the group of stories she calls 'Clever Women, Resourceful Girls.' They are women doing what they need to do to get what they want, such as a tale from the American Ozark mountain area about a hard-working girl and her rather lazy, ornery sister who does nothing all day and is tarred as a result.

The next day, the ornery girl went out to get her some gold, too. Pretty soon she seen a cow, and the cow says, 'For God's sake milk me, my bag's about to bust!' But the ornery girl just kicked the old cow in the belly, and went right on. Pretty soon, she sees an apple tree, and the tree says, 'For God's sake, pick these apples, or I'll break plumb down!' But the ornery girl just laughed, and went right on. Pretty soon she seen some cornbread a-baking, and the bread says, 'For God's sake take me out, I'm a-burning up!' But the ornery girl didn't pay no mind, and went right on. A little old man come along just then, and he throwed a kettle of tar so it stuck all over her. When the ornery girl got home she was so black the old woman didn't know who it was. The folks tried everything they could, and finally they got most of the tar off. But the ornery girl always looked kind of ugly after that, and she never done any good. It served the little bitch right, too.

From The Good Girl and the Ornery Girl (North American: Ozarks)

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood.

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood.Or a wonderful young Russian girl who was fond of vodka and did everything in an "unmaidenly" way. Her confusing behaviour so deceived the King that he became obsessed with knowing her true gender.

After dinner the king said: Vasilyevich, to come with me to the bath?' 'Certainly, Your Majesty,' Vasilisa Vasilyevna answered, 'I have not had a bath for a long time and should like very much to steam myself.' So they went together to the bathhouse. While King Barkhat undressed in the anteroom, she took her bath and left. So the king did not catch her in the bath either. Having left the bathhouse, Vasilisa Vasilyevna wrote a note to the king and ordered the servants to hand it to him when he came out. And this note ran: 'Ah, King Barkhat, raven that you are, you could not surprise the falcon in the garden! For I am not Vasily Vasilyevich, but Vasilisa Vasilyevna.' And so King Barkhat got nothing for all his trouble; for Vasilisa Vasilyevna was a clever girl, and very pretty too!

From Vasilisa the Priest's Daughter (Russian)

The cunningness of women to break society's expectations is echoed in a Norwegian story about a rich, powerful farmer who tries to make his beloved jealous by pretending to marry a horse and then ends up fancying the horse. And a devious, powerful woman who trades on her husband's love and trust to get what she wants.

A woman was so mad with love for her lover that she gave him all the rice in the bin, and had to fill it with chaff so that her husband would not notice what she had done. By and by the days for sowing came round, and the woman knew she could no more deceive her husband. One day her husband went to plough his field which lay near a tank. The next morning his wife went very early to the tank, made herself naked and smeared mud all over her body. She sat down in the grass waiting for him. When he came, she suddenly stood up and in a loud voice cried, 'I am going to take away your two bullocks. But if you need them you can give me the grain in your bin and I will fill it with chaff instead. But one or the other I must have, for I am hungry.' The man at once said that the Goddess - for so he thought her- should take the grain, for he knew he would be ruined if he lost his bullocks. 'Very well,' said the wife. 'Go back now to your house, and you will find that I have taken your grain, but I have put chaff in its place.' So saying she disappeared into the tank. The man ran home and found in fact that all the grain was gone and his bin was full of chaff. His wife quickly bathed and changed her clothes, and came home by way of the well in where she told the other women the story with great pride.

The Resourceful Wife (Indian Tribal)

Oftentimes, the narrative is subsumed by the greatness of the character.

Sermerssuaq was so powerful that she could lift a kayak on the tips of three fingers. She could kill a seal merely by drumming on its head with her fists. She could rip asunder a fox or hare. Once, she arm-wrestled with Qasordlanguaq, another powerful woman, and beat her so easily that she said: 'Poor Qasordlanguaq could not even beat one of her own lice at arm-wrestling.' Most men she could beat and then she would tell them: 'Where were you when the testicles were given out?' Sometimes, this Sermerssuaq would show off her clitoris. It was so big that the skin of a fox would not fully cover it. Aja, and she was the mother of nine children, too!

From Sermerssuaq (Innuit)

Yet Carter is unequivocal that the fairy tales are not a summary of a type of women but a gathering or celebration of all types.

Sisters under the skin we might be, but that doesn't mean we've got much in common. I wanted to demonstrate the extraordinary richness and diversity of responses to the same common predicament - being alive - and the richness and diversity with which femininity, in practice, is represented in "unofficial" culture: its strategies, its plots, its hard work.

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood.

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood.That woman would figure prominently as the heroine - the subject doing things rather than an object having things done to her - feels obvious. The nature of creating and perpetuating fairy tales has an unmissable connection to the traditional feminine: first, a vital aspect of domesticity told around the hearth or at bedtimes, and second, the storytellers were frequently women - consider Old Wives's Tales and Mother Goose. Angela Carter's passionate assemblage resonates with this connection:

I don't offer these stories in a spirit of nostalgia; that past was hard, cruel and especially inimical to women, whatever desperate stratagems we employed to get a little bit of our own way. But I do offer them in a valedictory spirit as a reminder of how wise, clever, perceptive, occasionally lyrical, eccentric, sometimes downright crazy our great-grandmothers were, and their great-grandmothers, and of the contributions to the literature of Mother Goose and her goslings.