"Fear is a natural reaction to moving closer to the truth."

The history of fear is the history of confrontation and externalisation: as we stand here, something we fear is over there. Something awaits to embrace, attack, or be indifferent to us. Borges had a lifelong fear of mirrors, a confrontation of self externalised. Toni Morrison boldly argued that fear creates our capacity to "other" one another, creating an artificial distance between humans otherwise connected. To be in fear is to be face-to-face with something. But what?

Fear might divide us, but it is also something we share: from insect to human (maybe that is why so many of us like watching insects; we see a flicker of ourselves.) Pema Chödrön (Born July 14, 1936), a Tibetan monk and nun at one of the first Buddhist schools in the Western Hemisphere, seizes this universality and expands it:

Fear is a universal experience. Even the smallest insect feels it. We wade in the tidal pools and put our finger near the soft, open bodies of sea anemones, and they close up. Everything spontaneously does that. it's not terrible that we feel fear when faced with the unknown. It is part of being alive, something we all share. We react against the possibility of loneliness, death, or not having anything to hold on to. Fear is a natural reaction to moving closer to the truth.

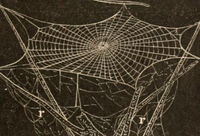

"A horizontal snare, fully orbed." Illustration from Henry C. McCook's American Spiders and their Spinning Work. A Natural History of the Orb-weaving Spiders of the United States with Special Regard to Their Industry and Habits published in 1889-93. McCook was a Civil War soldier for the Union army, a clergyman, a naturalist, and a published author on religion, history, and nature.

"A horizontal snare, fully orbed." Illustration from Henry C. McCook's American Spiders and their Spinning Work. A Natural History of the Orb-weaving Spiders of the United States with Special Regard to Their Industry and Habits published in 1889-93. McCook was a Civil War soldier for the Union army, a clergyman, a naturalist, and a published author on religion, history, and nature."In 1995, I took a sabbatical," Chödrön continues. "For twelve months, I essentially did nothing. It was the most spiritually inspiring time of my life. Pretty much all I did was relax." While sitting and facing fear, whatever form that fear took - Chödrön produced the mediative guide: When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times.

During a long retreat, I had what seemed to me the earthshaking revelation that we could not be in the present and run our storylines at the same time! It sounds obvious, but when you discover something like this for yourself, it changes you. Impermanence becomes vivid in the present moment; so do compassion, wonder and courage. And so does fear. In fact, anyone who stands on the edge of the unknown, fully in the present without a reference point, experiences groundlessness. That's when our understanding goes deep when we find that the present moment is a pretty vulnerable place and that this can be completely unnerving and completely tender at the same time.

Elsewhere in this generous book, Chödrön writes about letting tenderness seep into the space created when everything falls apart. Sitting in fear, letting tenderness in, what does this actually mean or look like? It sounds terrifying. Is it?

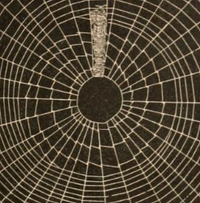

"Flossy circular braces of Uloborus." McCook's observant book about spiders and their webs was illustrated by Daniel Carter Beard, the founder of the Boy Scouts of America.

"Flossy circular braces of Uloborus." McCook's observant book about spiders and their webs was illustrated by Daniel Carter Beard, the founder of the Boy Scouts of America.Chödrön recounts a story about a man determined to face his limitations, including anger, pride, and laziness. His Buddhist teacher sent him to meditate in a small mountainside cabin. As the darkness fell, he noticed a shape in the corner of the hut: a snake. Fear flooded his body, and he faced both it and the snake. (Perhaps they are the same thing?)

Just before dawn, the last candle went out, and he began to cry. He cried not in despair but from tenderness. He felt the longing of all the animals and people in the world; he knew their alienation and their struggle. All his meditation had been nothing but further separation and struggle. He accepted- really accepted wholeheartedly- that he was angry and jealous, that he resisted and struggled, and that he was afraid. He accepted that he was also precious beyond measure-wise and foolish, rich and poor, and totally unfathomable. He felt so much gratitude that in the total darkness, he stood up, walked toward the snake, and bowed. Then he fell sound asleep on the floor. When he awoke, the snake was gone. He never knew if it was his imagination or if it had really been there, and it didn't seem to matter. As he put it at the end of the lecture, that much intimacy with fear caused his dramas to collapse, and the world around him finally got through.

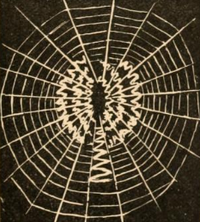

"Semicircular zigzag cords in the hub of Argiope." I chose these illustrations because I have a spider critter who represents "truth" in The Examined Life. Learn more.

"Semicircular zigzag cords in the hub of Argiope." I chose these illustrations because I have a spider critter who represents "truth" in The Examined Life. Learn more.We face fear, but what is fear? What is it that faces us? What is the snake? An emissary of death? We have an unknowable real mortality, the intellectual concept of death, but an emotional detachment from its premise. We cannot feel death, only imagine it.

Even then, it does not present as death but merely loss—the loss of our imagined, infinite storyline of our existence. The introduction of pain that will drag us down and hold us back, the things we imagine for ourselves. No wonder C. S. Lewis wrote, "I never knew grief was so much like fear."

"The ribbon brace of Acrosoma." Per Chödrön's loving advice: "Fear is a natural reaction to moving closer to the truth.

"The ribbon brace of Acrosoma." Per Chödrön's loving advice: "Fear is a natural reaction to moving closer to the truth.During her year of sitting in fear, Chödrön embraces the incredible loss of how she imagined herself in the world, to others and herself. She mourns what will never be as she steps away from that projected self.

Usually, we think that brave people have no fear. The truth is that they are intimate with fear. When I was first married, my husband said I was among the bravest people he knew. When I asked him why, he said I was a complete coward but went ahead and did things anyway.

It is intrinsic for us to want to keep our humanity intact and alive. Death is the opposite of moments of deep, resonant awareness rooted in senses and surroundings. I feel hollow when I wonder, 'Who will be thinking these thoughts if not me?' What we create might be gone, but what we think and feel - even fear - we all think of these thoughts. "That is where the courage comes in", Chödrön warmly promises. What surprised me most was this quick line: "Keep exploring; fear is not what we thought." I love the idea of fear as new, unexperienced, something yet to be discovered and conquered.