“Joy was not a deception. Its visitations were the moments of clearest consciousness we had.”

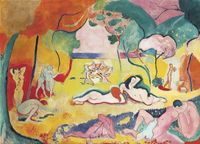

What is the feeling of joy? Is it, as artist Mark Hearld exudes, a raucous wellspring of all creativity? Or perhaps it is framed in Henri Matisse's 1905 crowd-shocker Bonheur de Vie (Joy of Life), with a carnal Bacchanalia of pleasure and happiness. I feel joy as rebellion: throwing off things that are and summoning things that could be.

Henri Matisse's "Le bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life)", 1905. Learn more.

Henri Matisse's "Le bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life)", 1905. Learn more.Novelist C. S. Lewis (November 29, 1898 - November 22, 1963), creator of Narnia and author of lucid self-examination, takes a more intimate view in Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life. Lewis describes how his childhood was bounded and built by three circumstances: solitude "always at my command"; a physical condition that left him with one thumb joint in his dominant hand, so he “couldn’t make anything" and was "forced to write”; and, finally, the vast, book-filled childhood home which made provided psycho-physical space to percolate the imagination.

Like George Orwell who professed a lonely child's habit of reading books, Lewis's childhood solitude, especially after the death of his mother and the departure of his brother to school, was the most impactful on his writing mind. "I am a product of long corridors, empty sunlit rooms, upstair indoor silences, attics explored in solitude, distant noises of gurgling cisterns and pipes, and the noise of wind under the tiles."

C. S. Lewis.

C. S. Lewis.Because of these circumstances, and maybe owing to others unmentioned, Lewis found joy to be an exquisitely complex internal reaction - akin to expanded consciousness - to external experiences. In Surprise by Joy, he details the three moments that could "only be called joy."

The first is itself the memory of a memory. As I stood beside a flowering currant bush on a summer suddenly arose in me without warning, and as if from but of centuries, the memory of that depth not of years but of centuries, the earlier morning at the Old House when my brother had brought his toy garden into the nursery. It is difficult to find words strong enough for the sensation that came over me; Milton's 'enormous bliss' of Eden (giving the full, ancient meaning to 'enormous') comes somewhere near it. It was a sensation, of course, of desire; but desire for what? not, certainly, for a biscuit-tin filled with moss, nor even (though that came into it) for my own past. - and before I knew what I desired, the desire itself was gone, the whole glimpse withdrawn, the world turned commonplace again, or only stirred by a longing for the longing that had just ceased. It had taken only a moment of time, and in a certain sense, everything else that had ever happened to me was insignificant in comparison.

Lewis's second experience of joy also internalizes a moment of external beauty (some shape of beauty that lifts the pale). It will resonate with many who feel a seasonal shift into autumn and, on a deeper level, a consciousness around that shift: i.e. what autumn's explosion of life and death means for the world and us in it.

The second glimpse came through Squirrel Nutkin, through it only, though I loved all the Beatrix Potter books. But the rest of them were merely entertaining; it administered the shock; it was a trouble. It troubled me with what I can only describe as the Idea of Autumn. It sounds fantastic to say that one can be enamoured of a season, but that is something like what happened; and, as before, the experience was one of intense desire. And one went back to the book, not to gratify the desire (that was impossible - how can one possess Autumn?) but to re-awake it. And in this experience, there was the same surprise and sense of incalculable importance. It was something quite different from ordinary life and even from ordinary pleasure; something, as they would now say, 'in another dimension'...

Photograph by Ellen Vrana.

Photograph by Ellen Vrana.Joy, to Lewis, was not only a physical imposition - a stab - it was also this cauldron of compounding emotions, each building on the last to drive him to this psychophysical locale of desire and longing.

Lewis continues:

Instantly I was uplifted into huge regions of the northern sky; I desired with almost sickening intensity something never to be described (except that it is cold, spacious, severe, pale, and remote), and then, as in the other examples, found myself at the very same moment already falling out of that desire and wishing I were back in it.

This oneness with the universe (a body-filling transcendence that poet Mary Oliver, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and even physicist Alan Lightman have explored) was what Lewis means by expanded consciousness. An awareness of things hitherto unthought, unfelt, unknown.

His final instant of joy was a tender connection to poetry and finding within it the same experienced awakening and universality of feeling.

The third glimpse came through poetry. I had become fond of Longfellow's "Saga of King Olaf": fond of it in a casual, shallow way for its story and its vigorous rhythms. But then, quite different from such pleasures and like a voice from far more distant regions, there came a moment when I idly turned the pages of the book and found the unrhymed translation of Tegner's Drapa and read.

I heard a voice that cried.

Balder the beautiful

Is dead, is dead -

I knew nothing about Balder, but instantly uplifted into regions of northern sky, I desired with almost sickening intensity something never to be described.

Inspired by joy's warm stab, despairing at its loss, and left reeling in its echo, Lewis's descriptions of joy are moving and intimate.

I will underline the quality common to the three experiences; it is that of an unsatisfied desire, which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction. I call it Joy, which is here a technical term and must be sharply distinguished both from Happiness and from Pleasure. Joy (in my sense) has indeed one characteristic, and one only, in common with them; the fact that anyone who has experienced it will want it again. Apart from that, and considered only in its quality, it might almost equally well be called a particular kind of unhappiness or grief. But then it is a kind we want. I doubt whether anyone who has tasted it would ever exchange it for all the pleasures in the world. But then, Joy is never in our power, and pleasure often is.

Joy, while felt so intimately, is often not in our being to create. It demands a catalyst, a visual jump, a scene of beauty, a taught line of verse. Read more on the unexpected connectivity of disparate emotions, the soul-elevating connection to the eternal, and the deep aching longing for the impossible. Finally, read Lewis' massive, physical grief following the death of his life love, Joy Davidman (who wrote such touching love poetry to Lewis). His expanded consciousness serves him in everything he has created.