"The disease slips you away a little bit at a time and lets you watch it happen."

Is life viewed best through an aperture of death? Can one stand waist-deep in illness and gain a critical insight into the aforementioned life? Like movie critic Roger Ebert, who wrote in his memoirs, "I was diagnosed with cancers of the thyroid and jaw, I had difficult surgeries, lost the ability to speak, eat, or drink... it [is] difficult to walk easily and painful to stand. It is that person who is writing this book."

Former U.S. President Ulysses S Grant finished his notably empathetic memoirs a week before he died from aggressive cancer. Then there is Christopher Hitchens' stunningly lucid book Mortality, written as the author grasps his own death.

Vanitas IV, Dreams, After A.C.” 2015 by Paulette Tavormina. A few centuries ago, humans felt death awareness was a moral imperative. Not only would it remind viewers of life’s evanescence, but it would also invoke the perspective necessary for virtue and contemplation.

Vanitas IV, Dreams, After A.C.” 2015 by Paulette Tavormina. A few centuries ago, humans felt death awareness was a moral imperative. Not only would it remind viewers of life’s evanescence, but it would also invoke the perspective necessary for virtue and contemplation. Of course, these gentlemen are sound minds and deteriorating bodies. What if the author writes from the environs of a dying mind? Hitchens might have distinguished "I don't have a body, I am a body," but most of us cannot conceive that equivalency. Our mind is the position of our personhood, not a leg or hand. Should our minds deteriorate, we deteriorate at pace.

Neurologist Oliver Sacks once described a patient who could not sustain a thought for more than three seconds. The patient's sense of self was in constant upheaval. And yet we, and Sacks - are comforted by the fact that he was unaware of his existence relative to what we consider neural-typical.

This is not the case with dementia (of which Alzheimer's is the most common form).

"The disease slips you away and lets you watch it happen," novelist Terry Pratchett (April 28, 1948 – March 12, 2015) wrote nine months after his Alzheimer's diagnosis. A diagnosis that was initially quite hard to come by as our cognitive abilities ebb and flow naturally (and, scientists have discovered, peak in autumn).

I spoke to a fellow sufferer recently (or as I prefer to say, 'a person who is thoroughly annoyed with the fact they have dementia') who talked in the tones of a university lecturer and in every respect was quite capable of taking part in an animated conversation. Nevertheless, he could not see the teacup in front of him. His eyes knew that the cup was there; his brain was not passing along the information.

Terry Pratchett in 2001. Photograph by Tom Pilston

Terry Pratchett in 2001. Photograph by Tom PilstonIn 2007, before his sixtieth birthday, Pratchett noticed affected typing and "atrocious" spelling. He was told he had a "simple loss of brain cells due to aging" but fortunately pushed for a more robust diagnosis. A specialist gave him an MRI and confirmed Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA). "When I look back," Pratchett reflected in 2008, "I suspect there may be some truth in the speculation that dementia may be present in the body for quite some time before it can be diagnosed."

Pratchett kept his diagnosis private initially but eventually spoke publicly because he "felt he had a voice, and I should make it heard."

It is a strange life when you 'come out.' People get embarrassed, lower their voices, get lost for words... Fifty percent of Britons think there is a stigma surrounding dementia. Only twenty-five percent think there is still a stigma associated with cancer. People being told they were too young or intelligent to have dementia; of neighbours crossing the street and friends abandoning them - are like something from a horror novel. It seems that when you have cancer you are a brave battler against the disease, but when you have Alzheimer's, you are an old fart. That's how people see you. It makes you feel quite alone.

Having Alzheimer's (and many mental illnesses) in public means loneliness, an inverse relationship to one's utility to society. I was delighted to learn recently of a cafe in Japan called the Restaurant of Mistaken Orders. All of the servers are people living with dementia, and customers (aware that they might not get what they requested) find themselves expanding their minds to the contextualities of dementia.

Most people and communities are not this fortunate.

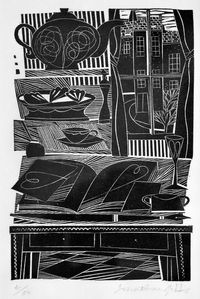

"Remembrance of Things Past" wood engraving by Jonathan Gibbs.

"Remembrance of Things Past" wood engraving by Jonathan Gibbs.As unbearable as social loneliness is, there is an even more profound loss in dementia: the loss of self. As Pratchett memorably describes: "The disease slips you away a little bit at a time and lets you watch it happen."

It occurred to me that at one point, it was like I had two diseases - one was Alzheimer's, and the other was knowing I had Alzheimer's. There were times when I thought I'd have been much happier not knowing, just accepting that I'd lost brain cells and one day they'd probably grow back or whatever.

When you are no longer you, where did you go? What remains? Pratchett describes "losing trust in himself" and angrily states, "it steals you from you." Dementia attacks the most precious, most defendable, and exhaustively human: the "I."

This loss, and more impactfully the self-awareness of this loss, echoes precisely what C. S. Lewis observed in his stunning observations from the loneliness of mourning and Joan Didion's similar observation, "And then, I remember" when she wrote about the sudden death of her husband.

Pratchett died in 2015, six years after his diagnosis. He did so much to raise dementia awareness during that short period.

It is better to know, though, and better for it to be known because it has got people talking, which I rather think was what I had in mind. The $1 million I pledged to Alzheimer's Research Trust was just to make them talk louder for a while.

[...]

At the time I was diagnosed if you had Alzheimer's of any kind there was nothing you could do, no one to ask for help, no golden path. I think after me, some of that at least got a little better.

Ultimately, Pratchett concluded, "You cannot battle it yourself." It reminded me of this beautiful diary entry from Jan Morris, journalist and historian, who at ninety-three still cared for her beloved, dementia-suffering wife, Elizabeth. Her casual words abound with love.

Half the world seems to be snarled up in the labyrinth that is Brexit... casual readers of mine send me their messages of sympathy for the appalling mess we British have got ourselves into - even the Scots and Welsh among us, who have always thought of ourselves as separate communities anyway. Nobody can escape the dilemma.

Except perhaps people like my dear old Elizabeth, who now half lives in the separate, cursed dominion of dementia. I remarked to her this morning, as I contemplated the day's televised complexities, that people of our age will never outlive the tangle of Brexit, but, bless her soul, she cheerfully told me she had never heard of it.

From Jan Morris' Thinking Again.