Fantasy works best when you take it seriously.

The humanities are not the only means or method for us to depart from reality, nor are sciences separate from realms of what might be seen as magic. Physicist Alan Lightman reckoned as much when he wrote, "Science is not the only avenue to arrive at knowledge," in his bold exploration of the universe's known and unknown.

Consider Darwin's discovery of fossilised ocean creatures on the top of a South American mountain or Galileo's use of self-made lens to ascertain mountains and craters on the moon's surface. Both discoveries immediately expanded what we knew as reality (although, in both cases, it took time for one discovery to change an entire civilisation.) Fantasy is imagining what is possible before the hypothesis is tested and proven. Fantasy must, however, adhere to rules, to reality. While fantasy throws us into the scarcely imaginable, it also boomerangs us back to reality so quickly we bruise from the impact.

No one championed the reality of fantasy more than self-proclaimed 'mainstream' author Terry Pratchett (April 28, 1948 – March 12, 2015). "Fantasy is more than wizards..." wrote Pratchett a decade before he died. He may as well have written that even wizards follow rules of gravity, communication, and a need for sleep.

Since a lot of fiction is in some way fantasy, can we narrow it down to 'fiction that transcends the rules of the known world? and it might help to add 'and includes elements commonly classed as magical'. there are said to be about five sub-genres, from contemporary to mythic, but they mix and merge and if the result is good, who cares?

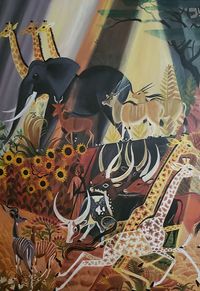

Dahlov Ipcar's "Zebra Wood", 1968. Ipcar was an American painter, writer, subsistence farmer, and children's book illustrator, including some by Goodnight Moon author Margaret Wise Brown. Learn more.

Dahlov Ipcar's "Zebra Wood", 1968. Ipcar was an American painter, writer, subsistence farmer, and children's book illustrator, including some by Goodnight Moon author Margaret Wise Brown. Learn more.Apply logic in places where it wasn't intended to exist. If assured that the Queen of the Fairies has a necklace made of broken promises, ask yourself what it looks like. If there is magic, where does it come from? Why isn't everyone using it? What rules will you have to give it to allow some tension in your story? How does society operate? Where does the food come from? You need to know how your world works.

When he was a child, C. S. Lewis concocted complex worlds of humanised animals - these worlds, with ruling structures, languages and many, many personas - made more sense to him than an often isolated reality. We must never forget to feel that child-like acceptance of things, what environmentalist Rachel Carson called a sense of wonder.

Somehow, we're trained in childhood not to ask questions of fantasy, like how come only one foot in an entire kingdom fits the glass slipper? But look at the world with a questioning eye, and inspiration will come. A vampire is repulsed by a crucifix? Then surely it can't dare open its eyes because everywhere it looks, in a world that is full of chairs, window frames, railings and fences, it will see something holy. If werewolves, as Hollywood presents them, were real, how would they make certain that when they turn back into human shape, they had a pair of pants to wear?

Dahlov Ipcar's "Cattle of the Sun", 1977. Ipcar also wrote four fantasy books, and her paintings represent real creatures - often animals - enhanced through her talented imagination. She died in 2017 at the age of 99. Learn more.

Dahlov Ipcar's "Cattle of the Sun", 1977. Ipcar also wrote four fantasy books, and her paintings represent real creatures - often animals - enhanced through her talented imagination. She died in 2017 at the age of 99. Learn more.Opening our minds and questioning what is expands far beyond trees having a unique language or the existence of dragons. What if we turned that imagination back onto ourselves? Is there a fantasy of human nature? What would it be? What could it be? Pratchett explores:

Fantasy is more than wizards... But it is also about the even more fantastic idea that humans are capable of intelligence as well. Far more beguiling than the idea that evil can be destroyed by throwing a piece of expensive jewellery into a volcano is the possibility that evil can be defused by talking. The fantasy of justice is more interesting than the fantasy of fairies and more truly fantastic.

Terry Pratchett in real life.

Terry Pratchett in real life.I'm obsessed by wacky, zany ideas. One is that rats might talk. But sometimes, I'm even capable of weirder, more ridiculous ideas, such as the possibility of a happy ending. Sometimes, when I'm really, really wacky and on a fresh dose of zany, I'm just capable of entertaining the fantastic idea that, in certain circumstances, Homo sapiens might actually be capable of thinking. It must be worth a go since we've tried everything else.

Pratchett's fellow fantasy author (who despised the term as much as Pratchett) Ursula le Guin wrote earnestly about the honour and rules of naming things in fantasy; there is a code we follow to create worlds which emanate from our own code as humans. Read more from Pratchett in A Slip of the Keyboard: Reflections on Life, Death and Hats in particular, a beautiful piece on his advancing dementia, a case in which the fantasy - a preposterous, destructive and in a word - evil - became his new realty as the dream of life slipped away.