"Gazing on other people's reality with curiosity, with detachment, the ubiquitous photographer operates as if its perspective is universal." Susan Sontag's timeless essay on the uniqueness of this modern art.

The trajectory of photography as an art form has been twofold: 1) the technological improvement of cameras such that they capture more and more light particles, and 2) a change in the proliferation of means - more cameras for more people that are easier and faster to use. It would be like rather than a few artists who access paints and brushes, we all carried paints and brushes all the time, and the world was our canvas. Such is photography. So is it still art?

Social philosopher and cultural critic Susan Sontag's (January 16, 1933 – December 28, 2004) 1977 essays, On Photography, on this most modern art form—written before personalised cameras—remain a lucid, practical review of photography, its limits, ethics, and how it functions as art.

Sontag realised, even before selfies and smartphones, that photography was essentially "gazing on other people's reality with curiosity, detachment, and professionalism." The voyeur had a tool that could turn the world into a frame. Through that technique, Sontag notes, "the ubiquitous photographer operates as if that activity... that perspective is universal."

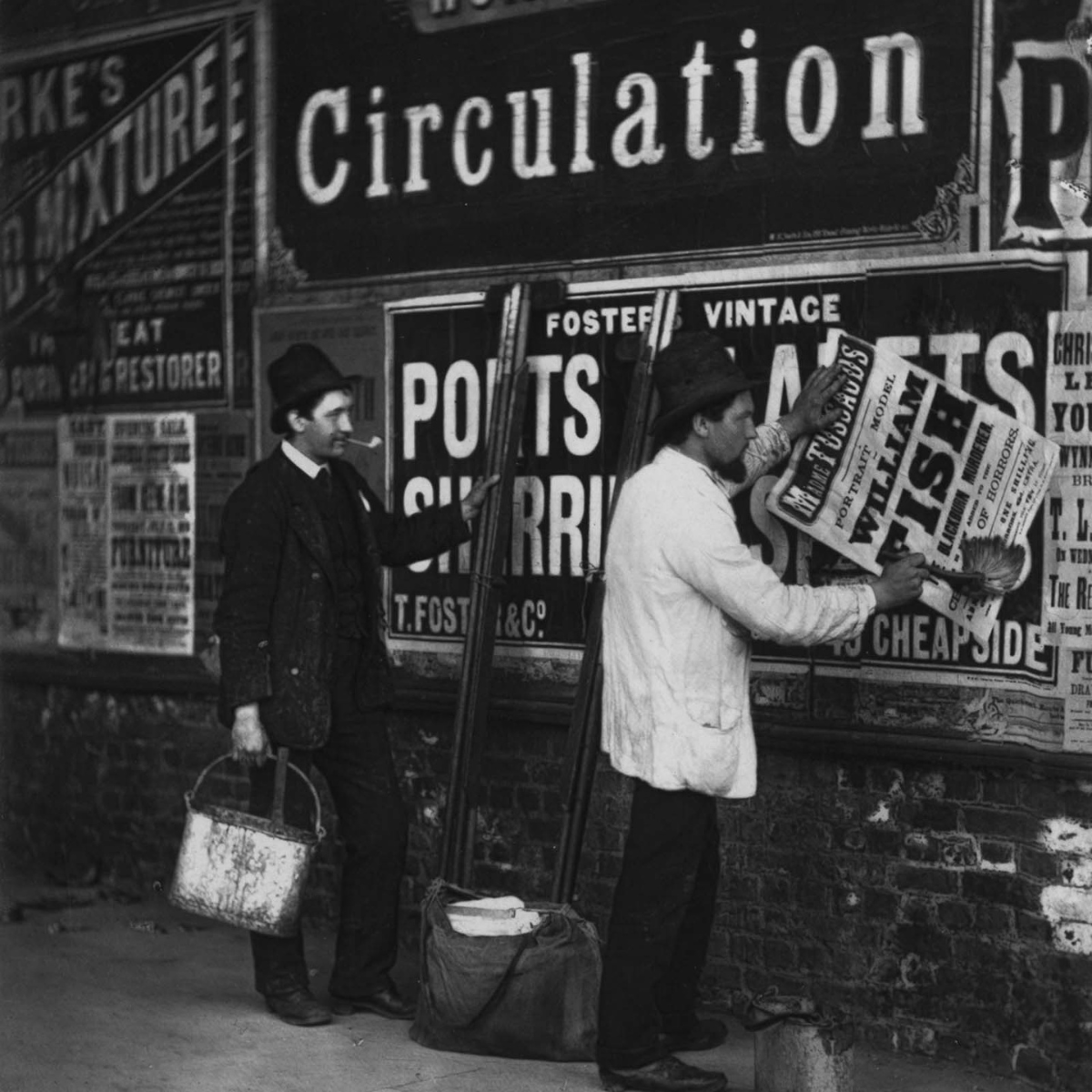

Stickers paste new advertising bills and remove the old ones. From John Thomson's Street Life in London, a collection of candid and sympathetic photographs of common trades taken between 1873 and 1877.

Stickers paste new advertising bills and remove the old ones. From John Thomson's Street Life in London, a collection of candid and sympathetic photographs of common trades taken between 1873 and 1877.Sontag could not have imagined the proliferation of cameras among the masses, making everyone a voyeur, a recorder of history. This would change exponentially when people turned the camera on themselves, changing the relationship between the subject and the photographer. But she still anticipated the possessiveness and power of self-portraits.

"As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people take possession of space in which they are insecure." This significance is perfectly illustrated by Andy Warhol's desire for artistic manipulation vis a vis the photograph. In his essays on what makes us human, Warhol wrote bluntly: "When I did my self-portrait, I left all the pimples out because you always should... Always omit the blemishes - they're not part of the good picture you want."

Sontag wrote On Photography only a few years after Andy Warhol took this self-portrait, about which he wrote in his autobiography: "Always omit the blemishes - they're not part of the good picture you want."

Sontag wrote On Photography only a few years after Andy Warhol took this self-portrait, about which he wrote in his autobiography: "Always omit the blemishes - they're not part of the good picture you want."Suddenly the photograph had a contradiction: what seems honest, true, and spontaneous is unreliably so. The realness of the technology was a lie. Alfred Stieglitz's famous Fifth Avenue photograph of a stagecoach in the snow happened. The horses' power, the air's wetness are indubitably real.

"Winter – Fifth Avenue" by Alfred Stieglitz, 1893.

"Winter – Fifth Avenue" by Alfred Stieglitz, 1893.The image itself omits, however, that Stieglitz sat outside in the snow for hours to take that exact photograph. Does that matter? Why is spontaneity expected in photographs? If they are not spontaneous, are they any less real? Does being real matter? Sontag reasons it is due to the thin line - often blurred in photography - between the original and the copy. "Photography has the unappealing reputation of being the most realistic, therefore facile, of the mimetic arts." Photography's mimetic nature promises truth.

But what truth? A photograph's distance from truth is inherent in this photograph of Francis Bacon's famously chaotic studio. We see a studio, imagine the artist, or even imagine we are intruding on his space. We will in the visual and emotional blanks.

Ireland, Dublin, Parnell Square, Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane, Francis Bacon Studio, reconstructed studio of painter Francis Bacon. Photograph by Danita Delimont.

Ireland, Dublin, Parnell Square, Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane, Francis Bacon Studio, reconstructed studio of painter Francis Bacon. Photograph by Danita Delimont.Except the studio in this photo isn't the original studio; it was reconstructed from its original location 7 Reece Mews in London to a museum-like space in Dublin. And the image does not show art, per se, but the detritus of art, the marginal art that doesn't show under the frame. And it certainly does not show Bacon at work or otherwise. So the photograph removes us from what we imagine is truth by about four degrees.

Sontag's view on photographs is that they are, most of the time, a medium rather than a form of art, like words are tools for literature or notes for music.

Although photography generates works that can be called art—it requires subjectivity, it can lie, and it gives aesthetic pleasure-photography is not an art form at all. Like language, it is a medium in which works of art (among other things) are made. Out of language, one can make scientific discourse, bureaucratic memoranda, love letters, grocery lists, and Balzac’s Paris. Out of photography, one can make passport pictures, weather photographs, and Atget’s Paris. Photography is not an art like, say, painting and poetry.

And yet (this is my favourite part of the essay) there is art within all of this complicated technique and the non-aesthetic automated machine. True, profound, real art. "The activity of exceptionally talented individual," Sontag notices, "Producing discrete objects that have value in themselves." This special quality of photographers to capture something that speaks to something more profound is exactly what Roland Barthes meant when he noted 'punctum': photographic details that catch and hold our attention. Sontag continues:

Although the activities of some photographers conform to the traditional notion of a fine art, the activity of exceptionally talented individuals producing discrete objects that have value in themselves, from the beginning photography has also lent itself to that notion of art which says that art is obsolete. The power of photography—and its centrality in present aesthetic concerns—is that it confirmed both ideas of art.

It is not only the caring, empathetic relationship between the photographer and subject matter that distinguishes this art, a balance of beholder and beheld, the artist and subject, but the very framing of it that makes it "always interesting and never entirely wrong."

Unlike the fine-art objects of pre-democratic eras, photographs don’t seem deeply beholden to the intentions of an artist. Rather, they owe their existence to a loose cooperation (quasi-magical, quasi-accidental) between photographer and subject—mediated by an ever simpler and more automatic machine, which is tireless and which, even when capricious, can produce a result that is interesting and never entirely wrong.

Read more from Sontag on the physical code of photography and the limits of empathy to physical images. Or jump headfirst into the space created by a photographer Jan Enklemann's bizarrely beautiful photos of London in Lockdown or ceramic artist Grayson Perry's rumination on saying something is art and making it so. The meaning of art is true but also elastic, and photography has not only tested those boundaries but expanded them beneficially.