"But when the melancholy fit shall fall, sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud..."

Patti Smith introduced her collection of wistful musings in Woolgathering with the following admission: "I truly loved my family and our home, yet that spring I experienced a terrible and inexpressible melancholy. I would sit for hours when my chores were done and the children at school, beneath the willows, lost in thought."

While Smith admitted that the composition of Woolgathering drew her from this stupor, I've always longed to gift Smith an edition of Seneca's short-form, almost aphoristic thoughts written nearly 2000 years ago. Seneca, a complex Stoic, wrote: "Do you think you are the only person to have had this experience? Are you really surprised, as if it were something unprecedented, that so long a tour and such a diversity of scene have not enabled you to throw off this melancholy?"

Regardless of how it arrives or departs, melancholy drips its mark across humankind. Perhaps it is a verbal code for what is now known as clinical depression, but I think humans have meant it as more than a mental malady. Melancholy has been referenced as a contradictory and even occasionally paralyzing state of being that combines almost everything - good and bad - at once.

When Smith used the word, how did she mean it? Did she consider Seneca?

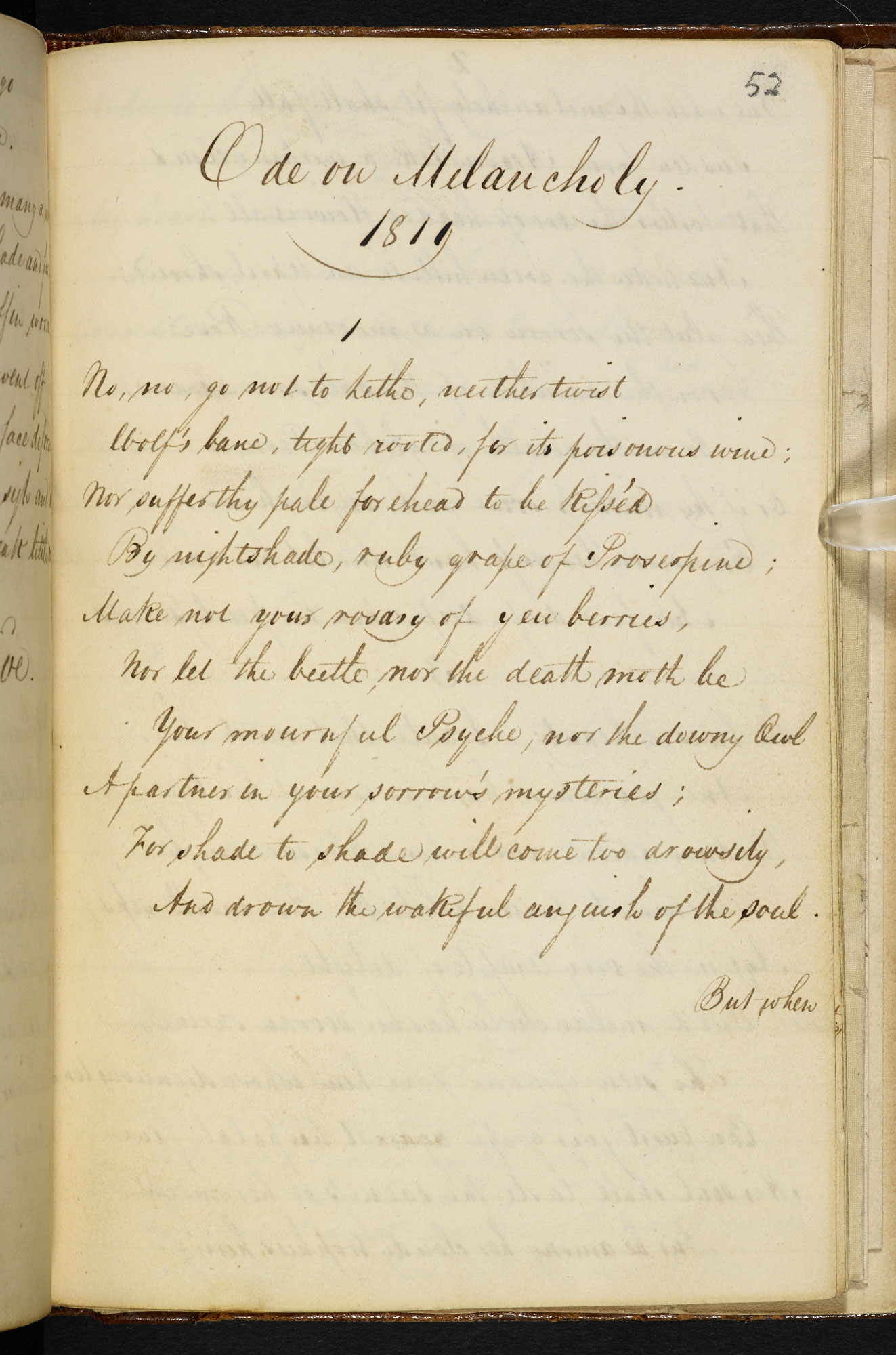

Or perhaps, as she sat under a weeping willow, she thought of poet John Keats (October 31, 1795 – February 23, 1821), whose 1819 "Ode to Melancholy" famously clasped sadness and beauty together in one emotional maelstrom.

Handwritten copy of "Ode to Melancholy" in 1819. Learn more.

Handwritten copy of "Ode to Melancholy" in 1819. Learn more.Ode to Melancholy

No, no, go not to Lethe, neither twist

Wolf's-bane, tight-rooted, for its poisonous wine;

Nor suffer thy pale forehead to be kiss'd

By nightshade, ruby grape of Proserpine;

Make not your rosary of yew-berries,

Nor let the beetle, nor the death-moth be

Your mournful Psyche, nor the downy owl

A partner in your sorrow's mysteries;

For shade to shade will come too drowsily,

And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul.

Keats' understanding of melancholy came a century before the late Victorians would classify it as a psychological issue and one hundred and fifty years before neurologists would pinpoint the brain's contributions to such feelings. From what imaginative alchemy was his poetry formed?

Keats professed to have read and adored Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy. Burton's work, first published in 1621, was a massive tome that explores the malady/affliction/emotion as: "[that] which goes and comes upon every small occasion of sorrow, need, sickness, trouble, fear, grief, passion, or perturbation of the mind, any manner of care, discontent, or thought, which causes anguish dullness, heaviness and vexation of spirit, anyways opposite to pleasure, mirth, joy, delight, causing forwardness in us, or a dislike."

Burton's work was published multiple times during the author's life but remained out of print until only a few years after Keats was born (around 1800). Thus, it resurged in popularity during the Romantic period. Keats employed significant nature and classical imagery to embellish the concept of melancholy. His Ode continues:

But when the melancholy fit shall fall

Sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud,

That fosters the droop-headed flowers all,

And hides the green hill in an April shroud;

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

Or on the wealth of globed peonies;

Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows,

Emprison her soft hand, and let her rave,

And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes.

Of course, Burton's rendition was undoubtedly influenced by Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia I, a vast engraving that depicted a female alone and thoughtful, done by the Renaissance artist in 1513. Is she melencolia or experiencing it?

Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia I, 1513. The artist's intent in the piece is vastly undocumented, so much speculation has been about its meaning. Learn more.

Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia I, 1513. The artist's intent in the piece is vastly undocumented, so much speculation has been about its meaning. Learn more.Keats wrapped his intense feelings, doubt, and hopes for fulfillment into the word "melancholia." Pleasure, i.e., beauty, which moves aside the pale and lifts our chin to the spectral infinite, is intimately connected to pain. The most famous line from his epic poem "Endymion" is "A thing of beauty is a joy forever..." is given a coda in "Ode of Melancholy:" "She dwells with Beauty-Beauty that must die." Beauty might be truth, but beauty is as mortal as we are.

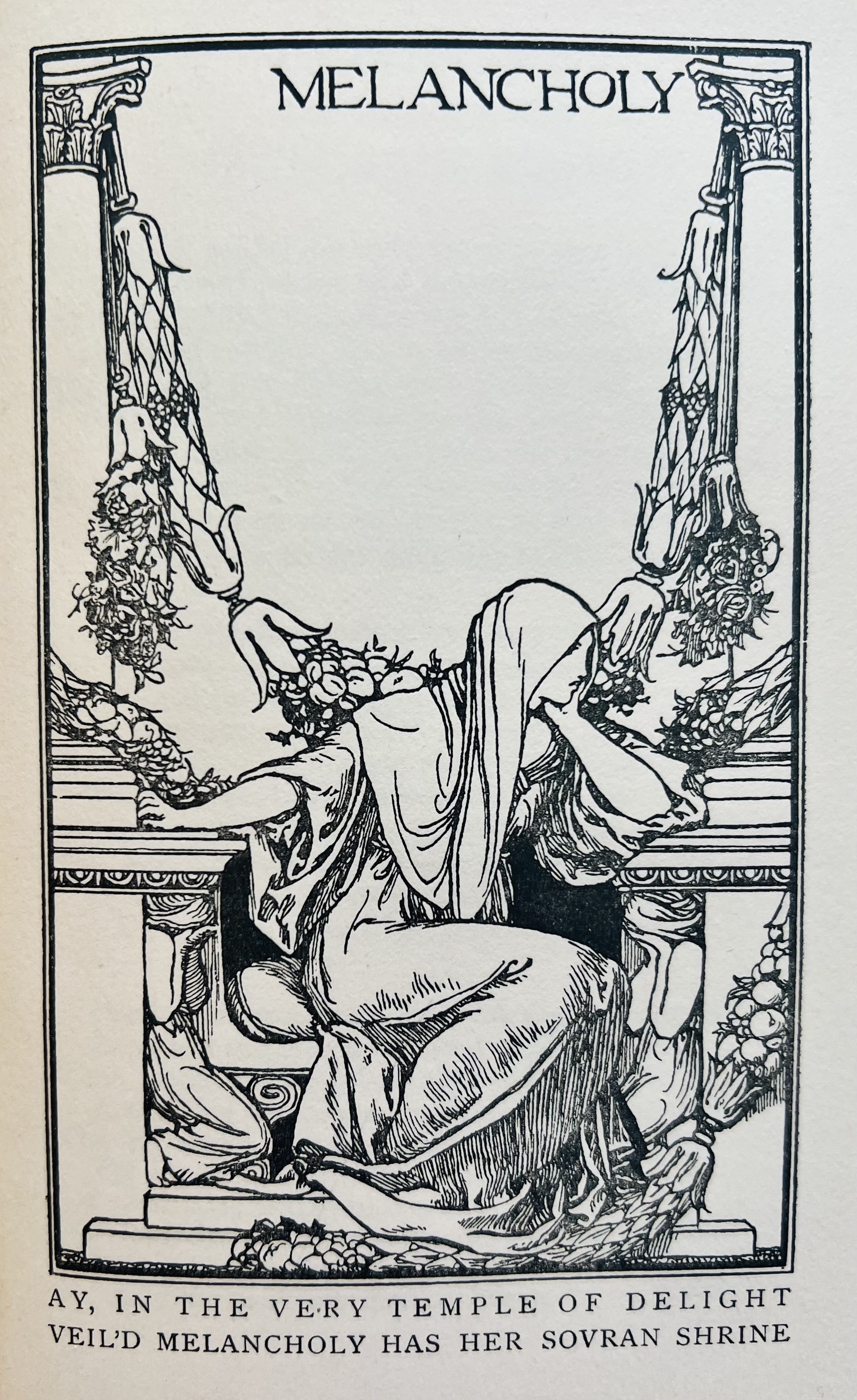

Robert Anning Bell's Arts & Crafts style illustration for a 1909 edition of Keats's major works also depicts melancholy as a female.

Robert Anning Bell's Arts & Crafts style illustration for a 1909 edition of Keats's major works also depicts melancholy as a female."Ode to Melancholy" was one of five odes Keats wrote in the spring of 1819. The ode is an "open form of the lyrical verse," according to the entertaining Stephen Fry in his uncanny The Ode Less Traveled: Unlocking the Poet Within. Fry writes that Keats' attempt to fashion the ancient poetic form in a more useable couplet. Without Keats's modernization of the form, it could have been forgotten.

She dwells with Beauty-Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy's grape against his palate fine;

His soul shall taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.

Much has been written about the poetic personality - much by Keats himself and the poem's nature. A turning loose of emotion, a departure from feeling, an utterly egoless venture... and so on. But the ego and its contradictory nature compel poetry in the first place. "Poetry makes everything great... " Keats admitted in a letter to his brother written the day before he completed his last (and I think most perfected ode)"To Autumn."

"Keats Walk" alongside the River Itchen, Winchester. Keats composed "Ode To Autumn" while staying here in the spring of 1819. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.

"Keats Walk" alongside the River Itchen, Winchester. Keats composed "Ode To Autumn" while staying here in the spring of 1819. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.Melancholy dwells with beauty - and in beauty, there is melancholy. This complex reality cuts through Keats' verbal metaphor to remind us that we can avoid poison: wolf's bane, nightshade, and yew-berries he mentions are all toxic, while the pomegranate seed functioned as Hades' lure. We can plummet our noses into peonies, but melancholy is not romantic. Despite his verse, Keats would agree and likely show you the blood from his quickly deteriorating tuberculosis-infected lungs. If he achieved a poetic release, it was not because he plunged himself into feeling, as we imagine these Romantics did; it was to disconnect from feeling, even transcend it.

If melancholy is affiliated with beauty and the fading of beauty, it is also marked by thoughtfulness. The fulfillment of life might exist in examining the minds-eye, but the soul also needs outwardness. As late as March 1819, Keats wrote to his brother that he was contemplating a trip to Edinburgh to finish his physician's training, but he was afraid "I would not take kindly to it." The poet's profession was uncomfortable on his shoulders.

Charles Brown's pencil portrait of his friend John Keats, 1819. The poet, head in hand, strikes the same pensive and solitary pose as the figure in Dürer's masterpiece.

Charles Brown's pencil portrait of his friend John Keats, 1819. The poet, head in hand, strikes the same pensive and solitary pose as the figure in Dürer's masterpiece.Keats wrote in his poem "Sleep and Poetry": "May I overwhelm myself in Poesie.." and he ends his last written sonnet with the line: "And so live ever-or else swoon to death." Keats died less than two years after he wrote "Ode to Melancholy," as of the November before his death, he was unable to write and barely communicate. His death was hardly a swoon; it was grisly, as he knew it would be because he saw his mother and brother die from the same illness.

The great function of poetry is to give us back the situations of our dreams, noted French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, who wrote beautifully about our localization of abstract concepts. When I read "Ode to Melancholy," I think of a poet who knew he would die, knew how he would die, and yet desired to live beyond death, beyond life, in a dream perhaps.

We all have unknowable mortality and seek to extend beyond our embodied self. What Mary Oliver called "staying in the stream" and Toni Morrison called the necessity of life, what Rollo May noted was immortality of creating. It is a blessed thing, stepping out from the weeping cloud of melancholy into a consummate oneness with something more significant.