A front-row seat to writer Lydia Davis improving her writing.

"I would force myself to stay at the desk for a number of hours, writing whatever came to mind - often descriptions of what I could see or hear, or thoughts or memories - as a way of bringing myself to the point of writing something like a story."

The literary world is teaming with books on writers exploring their writing. I've included many in The Examined Life Library, from George Orwell's impulse to depower injustice to Zadie Smith's resolute stance on art's power for change.

As ubiquitous as these books seem to be, rarely, however, do writers peel back the curtain to reveal the thought alchemy that evolves a novel, a scene, let alone a sentence. What is the journey from draft to final? Is it linear or circuitous change? On what measure of quality do writers make decisions? Is it truly the day-on-day work of adding one word after another (what Anne Lamott called 'taking it bird by bird')?

Of course, we can trust the efficient, reliable, and fantastically gifted Lydia Davis (born July 15, 1947) for an unsheathed glimpse into the workshop. In her essay "Commentary on One Very Short Story ('In a House Besieged')," Davis tells of a time in 1973 when she was twenty-six, living in France and pulling from sense and memory to "write something like a story." Davis wrote in her notebook for several hours, detailing "whatever came to mind."

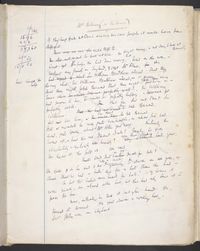

Virginia Woolf's notebooks for Mrs. Dalloway, 1925 which demonstrated the author's innovative 'stream of consciousness' writing. Learn more.

Virginia Woolf's notebooks for Mrs. Dalloway, 1925 which demonstrated the author's innovative 'stream of consciousness' writing. Learn more.This particular very, very short story - a style for which Davis is beloved not in the least by The Examined Life - grew out of her immediate situation and notebook entries. "The essay's title: "Commentary on One Very Short Story ('In a House Besieged')" arms us with foreknowledge of its content.

Namely, how does this:

First version: [IN A HOUSE BESIEGED]

In a house besieged lived a man and a woman, with two dogs and two cats. There were mice there too, but they were not acknowledged. Around the From [where they cowered in] the kitchen the man and woman heard small explosions. "The wind," said the woman. "Hunters," said the man. "Smoke," said the woman. "The army," said the man. The woman wanted to go home, but she was already at home, there in the middle of the country in a house besieged, in a house that belonged to someone else.

...turn into this?

Final version: IN A HOUSE BESIEGED

In a house besieged lived a man and a woman. From where they cowered in the kitchen the man and woman heard small explosions. "The wind," said the woman. "Hunters," said the man. “The rain," said the woman. "The army," said the man. The woman wanted to go home, but she was already home, there in the middle of the country in a house besieged.

Davis walks us around the writing and the fragments of reality that fed her imagination.

There were, in fact, hunters and army units in the countryside around the house. "In a House Besieged" grew directly out of my situation and the descriptions I wrote in the notebook! ... The animals were part of my real situation.

As for the changes to the actual story, her revisions are so obvious they seem almost pedantic. Remove distractions and the intimation of safety, and the story improves.

The two cats and two dogs, as well as the mice, were cut, I probably felt that they lessened the ominousness of the story, "domesticated" it, and certainly the bit about acknowledging the mice was chatty and distracting - getting away from the point of the story.

Second draft of Hanif Kureishi's "The Buddha of Suburbia" with Kureishi's hand-written revisions, 1990. Learn more.

Second draft of Hanif Kureishi's "The Buddha of Suburbia" with Kureishi's hand-written revisions, 1990. Learn more.Davis's writing craft focuses on the most minimal of minimal realism. She won the Man Booker International Prize in 2013 for her hard-to-define fiction that is neither short story nor poetry but connects the brilliance of both genres: dramatic narrative and careful word selection.

Her revisions to "In a House Besieged" continue:

The insertion of "where they cowered in" adds explicit drama, whereas if I had said simply "from the kitchen," the drama would be less, especially since kitchen has comfortable associations (until one has to cower in it). The change from "smoke" to "rain" replaces something inaudible by something audible.

Davis's "In a House Besieged" reminded me of another hard-to-define book, The Doubtful Guest, written and illustrated by American artist Edward Gorey. Guest carries the same ominous feeling of unending siege, also captured in precise lines like: "It came seventeen years ago - and to this day, it has shown no intention of going away." The "what" that is doing the besieging is unknown in both Gorey's tale and Davis's "House Besieged," which undoubtedly makes it more frightening.

Davis strengthens the story with a few more changes and a final word check.

Ending the story on the phrase "in a house besieged," especially if it echoes the title-though the title was added later-is stronger than the rather anticlimactic and irrelevant "in a house that belonged to someone else"; it is confusing and adds new information that is beside the point. Last change: By the time of the final version, I knew how to spell besieged.

Read more on Davis's inspirations and influences in Essays, one of my favorite books in the writers-on-writing genre. How many words are necessary to convey emotion? To tell a story? To make a reader feel fear? Few, Davis has proven, provided they are the best for the job.