"Ghosts are the tags and rags of everyday life, information you acquire that you don't know what to do with, knowledge that you can't process."

According to British writer Laurie Lee, who has done much of it, autobiographical writing is both "laying to bed the ghosts and ordering of the mind." What are these ghosts? In everyday life of a human being, what spirits follow us, surround us and lift, budge under the skin, and tumble out of our breath?

"Ghosts are the tags and rags of everyday life, the information you acquire that you don't know what to do with, a knowledge that you can't process," Dame Hilary Mantel (July 6, 1952 – September 22, 2022) explains in her memoir of childhood, Giving Up the Ghost. But ghosts are deeper than facts and wider than knowledge.

For Mantel, a British novelist of extraordinary talent (officially untrained, which is always important to mention), the ghost is more than the mere memory of what once was and the projection of what could have been. The real literal encounter with a thing beyond words that can only be accurately captured in "ghost." It is relinquishing the actual encounters that led to these ghosts in the first place.

A ghost in the garden... more on that in a bit.

Photograph by conservationist Joshua Burch, an excellent British-based photographer and generous collaborator with The Examined Life.

Photograph by conservationist Joshua Burch, an excellent British-based photographer and generous collaborator with The Examined Life.A contemporary of Mantel, British writer A. S. Byatt authored a short story called "The Thing in the Forest," which I have read and reread and then reread to turn into sense. I cannot. I simply cannot. It's about a group of girls that go to a country house during WWII. To be saved and removed from the bombings. One girl dies, or we assume she dies, but that isn't the plot. The plot is two girls, Primrose and Posey (or some other innocuous horticulture-inspired names), who run away into the forest and see something so supremely horrid that although it is precisely described for at least two paragraphs, its appearance is utterly mysterious.

I cannot make sense of it. I have written down all the details and even tried to draw them. And yet it is wildly, significantly familiar. Visual, verbal, and even imaginative language needs to catch up to this childhood horror.

I knew the feeling, if not the knowledge of childhood fear. Does that make sense to you?

It would indubitably make sense to Mantel. She saw a thing in the forest. That completely upending and unshakeable experience, something that sits heavy on your solar plexus and breathes in and out as you do. The ghost is not the ghost but the reminder and memory of the spirit. The knowledge you cannot process yet you retain all the same.

The knowledge came before the thing. The knowledge we all pass through as children and severed our innocence as it strengthens our consciousness: self-awareness, the personhood of parents (and their mortality), and our vast vulnerabilities to an indifferent world.

Mantel remembers one of her first moments of self-knowledge.

Standing on the pier at Blackpool, I look down at the inky waves swirling. Again, the noise of nature, deeply conversational, too quick to catch: again the deeply conversational, too quite to catch; again the rushing movement, blue, deep, and far below. I look up at my mother and father. they are standing close together, talking over my head. A thought comes to me, so swift and strange that it feels like the first thought I have ever had. It strikes with piercing intensity, like a needle in the eye. The idea is this: I stop them from being happy. I, me, and only me. That mya father will throw me down on the rocks, down into the sea, that perhaps he will not do it, but some impulse in his heart thinks he ought. For what am I but a disposable, replaceable child? And without me, they would have a chance in life.

See more of Burch's intimate observational photographs here.

See more of Burch's intimate observational photographs here.Mantel had ill health almost her entire life, undiagnosed for a significant portion of time and misdiagnosed for an even more brutal bit. Finally, doctors realized it was severe endometriosis, which meant she was in terrible pain from the body's self-healing mechanisms. Mantel's constant bouts of fever and fatigue correlated with emotional pain. After the emotional event at Blackpool, Mantel fell ill for the first time:

The next thing is that I am in bed with a raging fever. My lungs are full to bursting. The water boils, frets, spumes. I am limp in the power of the current that rugs beneath the waves. To open my eyes, I have to force the weight of water off my eyelids. I am trying to die and I am trying to live. I open my eyes and see my mother looking down at me. She is sitting swiveled towards me, her anxious face peering down. She has made a fence of dining chairs and behind this barrier she sits, watching me. For a minute or two I swim up from under the water: clawing. I think, how beautiful she is.

She also carried a self-awareness of pain and the limits of parental love that, for the first years of our life, feels endless:

We can be made foreign to ourselves, suddenly, by illness, accident, misadventure, or hormonal caprice. I am four, and my mother tells me a story about myself: my hair was black and thick when I was born. At age five, I mourn for it, weaving in my mind the ghost of a black plait that trails over my right shoulder. I know there is no truth in this belief. But it has created a complex emotion in me: I feel nostalgia for the first time.

These moments add up and return to the apparition, to Mantel's thing in the garden. Was it a culmination of such vast, complex self-awareness, the limits of which a child cannot understand? Like the concurrent breakdown of her family as her mother's lover moved in and her father moved out? Or the awareness that her parents' happiness hinged on her presence/absence? What does a child do with all of this reality?

Humans have always invented creatures to explain what we cannot understand:

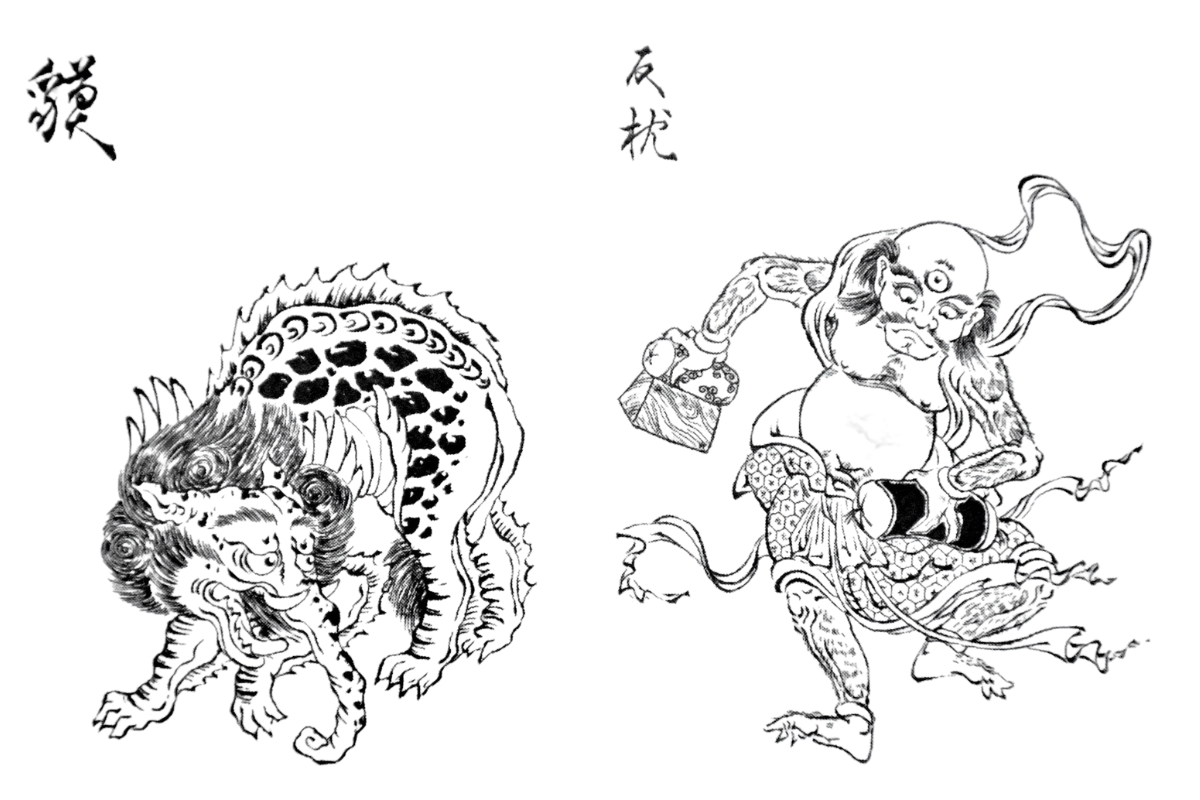

Baku, the "dream-eater," and Makura-Gaeshi, the "pillow shifter." Illustration by Japanese artist Shinonome Kijin for The Book of Yokai.

Baku, the "dream-eater," and Makura-Gaeshi, the "pillow shifter." Illustration by Japanese artist Shinonome Kijin for The Book of Yokai.I am seven, and I am in the yard playing near the house, near the back door. Something makes me look up: some shift of the light. My eyes are drawn to a spot beyond the yard, beyond its gate, in the long garden. It is, let us say, some fifty yards away, among coarse grass, weeds and bracken. I can't see anything, not exactly see: except the faintest movement, a ripple, a disturbance of the air. I can sense a spiral, a lazy buzzing swirl, like flies, but it is not flies. There is nothing to see. There is nothing to smell. There is nothing to hear. But its motion, its insolent shift, makes my stomach heave. I can sense at the periphery, the limit of all my senses - the dimensions of the creature. It is as high as a child of two. Its depth is a foot, and fifteen inches. The air stirs around it invisibly. I am cold and rinsed by nausea. I cannot move. I am shaking; pinned to the moment, I cannot wrench my gaze away. I am looking at a space occupied by nothing. It has no edges, mass, dimension, or shape except the formless; it moves. I beg it, stay away, stay away. Within the space of a thought, it is inside me and has set up a sick resonance within bones and in all the cavities of my body.

"I was never the same afterward," Mantel continues, "I was always doomy after that: and what was it anyway? Something intangible had come for me." Never the same after the ghost? Or never the same after imagining that one of her parents might hurt or leave her? None of us are the same after things shift our consciousness into unchartered paths.

I think about Mantel, her bright and much-pained life, and the weight of self-awareness she carried from such a young age. Was it inevitable that some of that pain would pass into a ghost? Or was it, indeed, as she believed her entire life, an unpalpable evil?

I don't know, nor did she. Perhaps it was evil. But evil is conceptual, not physical. Right?

In 1984 Joseph Brodsky, this Russian émigré (he was 'strongly advised' to leave his native Soviet Union), Nobel laureate, poet, and lyricist of tender memory and pain, addressed the graduating class of William's College and left the students with a fair warning:

No matter how daring or cautious you may choose to be, in the course of your life, you are bound to come into direct physical contact with what's known as Evil. I mean here not a property of the gothic novel but, to say the least, a palpable social reality that you in no way can control. No amount of good nature or cunning calculations will prevent this encounter. In fact, the more calculating, the more cautious you are, the greater the likelihood of this rendezvous, the harder its impact.

From Joseph Brodsky's Commencement Address at Williams College,

A recognition that there are bad things in the world is a knowledge difficult to process. Like the rotting souls of our fellow humans (or even ourselves). Do the most imaginative minds render that feeling into an apparition?

Mantel claimed she wanted to stay aged four forever when she imagined everything would always be good. "I have hesitated for such a long time before beginning this narrative," Mantel admits between pages of pain and reckoning. "For a long time, I felt like someone else was writing my life. This is a child's life; you have no rights over your life or death."

Photograph by Ellen Vrana

Photograph by Ellen VranaMantel died in 2022, suddenly, hopefully peacefully. She died of complications of a stroke, and I can't help but think that perhaps in those last moments, she did give up the ghost.

The phrase "giving up the ghost" means something leaving us in form or concept. It is fair to say that although Mantel laid her unknowledge to rest, she has not given up the ghost in our lives. Her absence is tolerated and must be accepted. she is no longer physically in the world but she is so very much on these pages. And in our hearts.

For other heart-overflowing memoirs of what I like to call "being and becoming," turn into poet Joy Harjo's memoir of poetry as salvation for a dispossessed being, beloved children's author Roald Dahl's extirpations of young adult ghosts, Mary Ruefle's delightful capture of the invisible everything that is imagination, and my look at how we place memory in space to localize our selves.