"I've decided to tear up everything that I've written and start again. I'm sure that is best. This misery persists, and I am so tired under it. If I could write with my old fluency for one day, the spell would be broken."

From John Steinbeck's private working journals that chronicled his self-implosion during the creation of his greatest novel, to Dani Shapiro's self-advice to sit down and stay there, writers with writer's block write about writer's block. As if to separate this ominous, grotesque thing from themselves and poke at it with incisive writing. Perhaps the only type of writing they can manage.

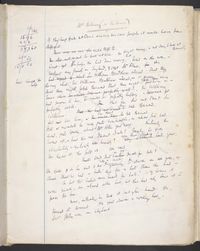

Virginia Woolf's notebooks for Mrs. Dalloway, 1925 which demonstrated the author's innovative 'stream of consciousness' writing. Learn more.

Virginia Woolf's notebooks for Mrs. Dalloway, 1925 which demonstrated the author's innovative 'stream of consciousness' writing. Learn more.From the stubbornness of thought to the full self-annihilation when nothing appears like it used to, the slings and arrows of writer's block (or any artistic block) interests me in so far as comparing how it feels to be an artist not functioning as an artist. The compulsion and pressure of being what one once was or what one imagines one could be, surely, creeps into the bones and infiltrates the mind. The two are deeply connected. Annie Dillard wrote about consciousness hitched to the writing arm, what happens to the consciousness when the arm is immobile?

C. S. Lewis documented the physical manifestations of grief, why not the writer's mental anguish? And if we connect our body to our mental anguish, is it any wonder we begin to unravel that body as well? That is exactly what happened to New Zealand author Katherine Mansfield (October 14, 1888 – January 9. 1923) whose writer's block (short-lived) in the spring season of 1916, five years after her first book of short stories was published to positive review and five years before her next compilation would be published. In her posthumously published collection of Letters and Journals, Mansfield writes about the experience in her characteristically open manner:

January 1916

Now, really, what is it that I do want to write? I ask myself, Am I less of a writer than I used to be? Is the need to write less urgent? Does it still seem as natural to me to seek that form of expression? Has speech fulfilled it? Do I ask anything more than to relate, to remember, to assure myself? There are times when these thoughts half-frighten me and very nearly convince. I say: You are now so fulfilled in your own being, in being alive, in living, in aspiring towards a greater sense of life and a deeper loving, the other thing has gone out of you.

The recent death of Mansfield's brother in WWI led to inscrutable emotional agony and Mansfield moved between London and the South of France with her husband John Middleton Murray to find a sense of establishment and rootedness. According to her journal, however, the writer's block persisted and soon, in the same entry, gave way to expansive writing related to her self and memory.

February 1916

Why am I not writing too? Why, feeling so rich, with the greater part of this to be written before I go back to England, do I not begin? If only I have the courage to press against the stiff swollen gate, all that lies within is mine; why do I linger for a moment? Because I am idle, out of the habit of work and spendthrift beyond belief. Really it is idleness, a kind of immense idleness - hateful and disgraceful.

[...]

I was thinking yesterday of my wasted, wasted early girlhood. My college life, which is such a vivid and detailed memory in one way, might never have contained a book or a lecture. I lived in the girls, the professor, the big, lovely building, the leaping fires in winter, and the abundant flowers in summer. The views out of the windows, all the patterns that were weaving. Nobody saw it, I felt, as I did. My mind was just like a squirrel. I gathered and gathered and hid away, for that long 'winter' when I should re-discover all this treasure - and if anybody came close I scuttled up the tallest, darkest tree and hid in the branches. And I was so awfully fascinated in watching Hall Griffin and all his tricks - thinking about him as he sat there, his private life, what he was like as a man, etc., etc. (He told us he and his brother once wrote an enormous poem called the Epic of the Hall Griffins.) Then it was only at rare intervals that something flashed through all this busyness, something about Spenser's Faerie Queene or Keats's Isabella or the Pot of Basil, and those flashes were always when I disagreed flatly with H.G. and wrote in my notes - This man is a fool.

When works and thoughts fail to gather or fail to detangle into substance, it is often best to create adjacent to the more instinctual talent. Rather than write, paint. If one cannot paint, suffer a tune. (I am one of the many writers who, lacking in other creative talents, immediately heads out to the garden to form something new from earth and water.) It need not be breathtaking, it merely needs to be original.

Come February 1916 Mansfield continued to write in her journals through and around her self-proclaimed inability to write fiction. Although we imagine the issues persist, we cannot see them directly. And yet, can we read a bit of self-flagellation in the subsequent lines about hunger?

February 1916

...I'm so hungry, simply empty, and seeing in my mind's eye just now a sirloin of beef, well browned with plenty of gravy and horseradish sauce and baked potatoes, I nearly sobbed. There's nothing here to eat except omelets and oranges and onions. It's cold, sunny, windy day - the kind of day when you want a tremendous feed for lunch and an armchair in front of the fire to boa-constrict in afterward...

And what about the self-doubt that rises up when Mansfield confronts her knowledge of literature?

But what coherent account could I give of the history of English Literature? And what of English History? None. When I think in dates and times the wrong people come in the right people are missing. When I read a play of Shakespeare I want to be able to place it in relation to what came before and what comes after. I want to realize what England was like then, at least a little, and what the people looked like (but even as I write I feel I can do this, at least the latter thing), but when a man is mentioned, even though the man is real, I don't want to set him on the right hand of Sam Johnson when he ought to be living under Shakespeare's. And this I often do.

As she steers her mind, and us the audience, through various thoughts and routes, Mansfield finds herself writing away the inability to write.

"Typewriter" linocut print by British printmaker Amanda Cardoso.

"Typewriter" linocut print by British printmaker Amanda Cardoso.Any artist has periods of unproductivity when whatever scaffold we've constructed with our last work folds like paper beneath us and sends the creative ego tumbling down. Mansfield's ability to write and write in another medium - quite lucidly, seems to have served her purpose. Later in the month, she wrote this poem, "Sanary," whose lines "She did not seem / To think, to feel or even to dream" hints distantly at her situation, allowing precision with its poetic metaphor.

Sanary

Her little hot room looked over the bay

Through a stiff palisade of glinting palms,

And there she would lie in the heat of the day,

Her dark head resting upon her arms,

So quiet, so still, she did not seem

To think, to feel, or even to dream.

The shimmering, blinding web of sea

Hung from the sky, and the spider sun

With busy frightening cruelty

Crawled over the sky and spun and spun.

She could see it still when she shut her eyes,

And the little boats caught in the web like flies.

Down below at this idle hour

Nobody walked in the dusty street;

A scent of dying mimosa flower

Lay on the air, bus sweet - too sweet.

Mansfield's particular writer's block - full of self-doubt, physical suffering and highly self-critical thinking - seemed to gestate for an entire season were we to read her Letters and Journals. And yet surprisingly, according to her husband, she was wonderfully productive during this time. This means she used her Journal, much like Steinbeck did thirty years later, as a way of gathering all the negative self aspects to allow her writing self to flourish (Steinbeck also used letter-writing to his best friend as a propulsive method). Read more on the fragile artistic ego; how artists begin their creative processes and Anne Lamott's most beautiful antidote for the overwhelmed writer, which is simply this: write one bird at a time.