Roald Dahl's letters to his mother Sofie Magdalene were at times pedantic, misleading, and occasionally impersonal. But he wrote to her faithfully throughout his life, and she, unknown to Roald, saved each one.

Every Sunday morning, after breakfast but before church, a young Roald Dahl wrote and postmarked a letter to his mother, Sofie Magdalene Dahl. Letter writing was required by his school but became a habit Dahl continued until his mother died more than three decades later. "I wrote her once a week," Dahl recollected in his book of childhood stories.

I wrote to her once a week, sometimes more often, whenever I was away from home. I wrote to her every week from St Peter's (I had to), and every week from my next school, Repton, and every week from Dar es Salaam in East Africa, where I went on my first job after leaving school, and then every week during the war from Kenya and Iraq and Egypt when I was flying with the RAF.

From Roald Dahl's Boy

From 1925 to 1965, Roald Roald (September 13, 1916 - November 23, 1990) wrote more than six hundred letters to his mother, Sofie Magdalene. Ms. Dahl saved each letter, most with envelopes, and the fact that she kept each one was only made known to Roald when she was dying. "I am awfully lucky to have something like this to refer to in my old age," he admitted tenderly.

Sofie Magdalene Dahl ne Hesselberg.

Sofie Magdalene Dahl ne Hesselberg.Sofie Magdalene Hesselberg, born in Norway in 1885, married Harald Dahl, a Norwegian widower twenty years her senior. Following the death of their youngest daughter from appendicitis, Harald himself died from grief (so supposed Roald), leaving the barely thirty-five-year-old Sofie as a single mother of four and pregnant with a fifth. Roald was the only son. Dahl tells a story in Boy involving his sister learning to drive, a traffic accident, a hostile chicken farmer, and Sofie who bent the entire situation to her will to find help for her child's (Roald's) suspected broken nose. Sofie's strength and fortitude leave us without doubt of her ferocity in the face of adversity and unbounded love for her children.

Roald Dahl and his elder sister Alfhild in their garden.

Roald Dahl and his elder sister Alfhild in their garden.Roald, named for a Norwegian explorer who reached the south pole, was three when his father died and remembered him vaguely. The Dahl family settled in Wales and persisted under Sofie's soft but relentless direction that the children would have proper English education. Dahl was sent to boarding school when he turned nine. It was the first time he had spent the night away from home, and he remembers crying when his mother left him. They remained in constant contact with one another. Dahl sent letters weekly, and his mother responded with sweets, fruit, chestnuts, and letters.

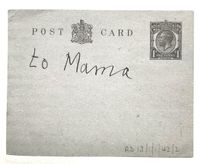

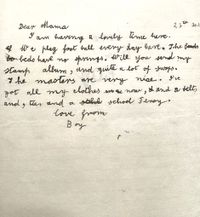

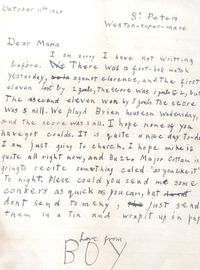

Roald's first letter in Love from Boy: Roald's Dahl's Letters to His Mother, thoughtfully compiled, edited, and introduced by Dahl's official biographer Donald Sturrock, dates from after he had enrolled at the boy's school in Weston-Super-Mare. It is a small epistle apologizing to his mother for not writing earlier and asking that she send conkers, shiny horse chestnuts used in children's games of the same name.

October 11th 1925

St Peter's

Weston-super-Mare

Dear Mama

I am sorry I have not writting before.Wethere was a foot-ball

match yestarday,so I aagenst clarence, and the first eleven lost by

2 goals, the score was 3 goals to 2, but the second eleven won by 5

goals the score was 5 nill. We playd Brien house on Wedensday,

and the score was 1 all. I hope none of you have got coalds. It is

quite a nice day to-day, I am just going to church. I hope mike is

quite all right now, and Buzz. Major Cottam is going to recite

something caled 'as you like it' to night. Plese could you send me

some conkers as quick as you can, butdoantdon't send to meny,thejust send them in a tin and wrap it up in paper.

Love from

BOY

The letters were penned under the watchful eye of the school's head, a man Dahl described as a giant with "one tooth edged all the way around in gold." This letter and others are extremely non-indicative of any of the troubles that beset the young author at school (there were many). Nevertheless, Dahl's letters to his mother functioned as a diary, including updates on what he did and was learning and occasionally, lengthy thoughts on his immediate life. The kind of news that would seem nothing at the time but present a kind of literary treasure twenty years or so after the fact.

November 29th 1925

St Peter's

Weston-super-Mare

Dear Mama

... We had a lecture last night on bird legends, it was fine, he told us that the wren was the king of birds, he said because the birds were going to have a test, and the one which could fly the highest would be king, and so they started, and the Eagle flew up and up until he could not go any further, nearly all the other birds had dropped out, just then the wren dropped out of the Eagle's feathers and managed to fly a few yards higher, so he was the [King of the] Birds. [...]

Love from

Boy

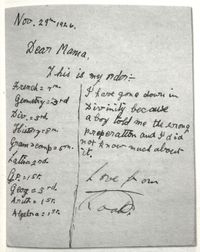

A letter from Roald Dahl in 1926 to his mother showing his subject ranking.

A letter from Roald Dahl in 1926 to his mother showing his subject ranking.[postmarked April 25th, 1932]

Priory House, Repton

Dear Mama,

I arrived here alright at 3 and went on by bus.

Had rather an amazing lunch on the train. First while I was

having my soup I leaned my Daily Mail I leaned it up against my

bottle of cider, and the bottle promptly decided to fall over:

much good cider on opposite seat. The next course was an egg

(poached) covered in Spaghetti!! Jolly good. Next a chicken with

breast meat on its legs! Probably a crow. During this course,

the waiter spilled a lot of bread sauce over my Daily Mail.

Very funny, but I couldn't read any more about Hitler for he was

covered with bread sauce.

Binks was very perturbed because at least six boys are not

coming back yet for various reasons. I had tea with him.Love from

Roald

Family and friends often noted that Dahl had a child-like quality throughout adulthood. These traits appear consistently in his letters to Sofie. They are always a bit formal but playful and expressive. The persistence and sheer volume of letters suggest the intimacy between mother and son. Although the correspondence obviously went in both directions, sadly, none of Sofie's letters remain.

November 3rd 1929

St Peter's

Weston-super-Mare

Somerset MTDear Mama

Thanks awfully for my pen and the chocs. The nib is not

functioning properly yet, but I hope that is only because it is

new; otherwise it is fine.

Roller-skating is going toppingly, and the whole school, with

the exception of about five is now on wheels!

I am glad you did'nt get me another pair of gymshoes; you

know, the ones I bought in Bexley and you said they smelt like a

cats crap. Well, they fit wonderfully on to my roller-skates, (or,

rather, the other way around), and on Friday when we box, we

are allowed to skate, and no one else is able to, much, because

roller-skates wont fit onto other gymshoes. Oh dash, I've just

dropped my pen onto the letter, and there isn't time to write it

out again. Incidentally, the pen thought it necessary to make a

blotch over a certain word [CRAP], but it did not quite succeed

in covering it up!!Love from

Roald

Throughout his writing, Dahl's letters would have been reviewed and censored by authorities, first the school and then the military. And yet beyond that, there is a protective tone, a son wanting to keep from his mom the horror of circumstances. In 1938 Dahl went with the Asiatic Petroleum Company to their Tanzania office in Dar es Salaam to manage ocal lpetrol distribution; he had been employed by them in London for four years and ached to travel abroad. He was stationed in Africa when Britain declared war on Germany.

He wrote to his mother:

At the time, I was actually out guarding the road

going down the South Coast to Kilwa and Lindi with 6 armed

native troops (Askaris) and an enormous barbed wire blockage

across the road. All I heard was a grim voice down the field

telephone which said - 'War has been declared - Stand by -

arrest all Germans attempting to leave or enter the town. Then

the fun started, and after a bit when I was relieved, I went into

the town to help with the work there, rounding them up in their

houses. I better not say any more or the ruddy censor might hold

up the letter.

Dahl does not tell his Mother but tells us in his memoirs Going Solo, that it fell on him as a voluntary officer to round up any Germans leaving town and deal with any who resisted. He was told specifically: 'all male Germans must be rounded up at the point of a gun and put into the prison camp.' Dahl also did not mention that one did resist, and Dahl shot and killed him.

Dear Mama,

I'm very sorry I haven't written to you for such ages but you can guess that things have been humming a bit here. Now all the Germans in the Territory, and it's a pretty big place in which to try to catch them, have been safely put inside an internment camp. And we army officers were the people who had to collect them.

[...]

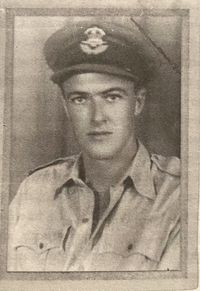

Roald Dahl, 1941.

Roald Dahl, 1941.When he was called to serve in the Royal Air Force a few weeks later, Dahl was sent to a training base six hundred miles north in Nairobi, Kenya. He drove the distance solo and carefully noted the animals he passed, momentarily escaping the fact that he would soon kill or be killed by Germans.

When one is quite alone on a lengthy and slightly hazardous journey like this, every sensation of pleasure and fear is enormously intensified, and several incidents from that stage two-day safari up through central Africa in my little black Ford have remained clear in my memory.

A frequent and always wonderful sight was the astonishing number of giraffe that I passed on the first day. They were usually in groups of three or four, often with a baby alongside, and that never ceased to enthrall me. They were surprisingly tame...

All my inhibitions would disappear and I would shout, 'Hello, giraffes! Hello! Hello! Hello! Hello! How are you today?'

And the giraffes would incline their heads very slightly and stare down at me with languorous demure expressions, but they never ran away. I found it exhilarating to be able to walk freely among such huge graceful wild creatures and talk to them as I wished.

From Roald Dahl's Going Solo

When he arrived to RAF training, Dahl, close to six feet seven, was far too large for the plane cockpits and had to duck down with a cloth over his face to breathe when flying. Nevertheless, he told his mother it was marvelously beautiful, and his flying team - who would all die but two - was great.

In October 1940, Dahl became disoriented while flying over the Libyan desert and crashed landed. He had a horrific head wound and could not see for a week. "When I got here, I was a bit of a mess...." he describes to his mother again, downplaying the urgency. He wrote her more detail when he was recuperating while on medical leave.

Dear Mama

At last I'm allowed to write, but I'm told that it's got to be a

short letter. Yesterday I received eight letters from you and one

from Alf and one from Else and one from Asta, dating back from

July right up to the last one you wrote in October from the cellar

at Oakwood, when Mrs. Creasey arrived in the middle. They'd

been all over Egypt and the desert before finally turning up, and

are the first I've had for two months.

I hope you're well settled now at Wayside Cottage and that it's

quite safe there. You seem to have had the hell of a time at

Oakwood. I expect you've written to tell me what's happened to

the house and the pictures and furniture. Did you take the best

pictures out of their frame and cart them off. I hope so.

I sent you a telegram yesterday saying that I'd got up for 2

hours and had a bath - so you'll see I'm making good progress. I

arrived here about eight and a half weeks ago, and was lying on

my back for 7 weeks doing nothing, then got up gradually, and

now I am walking about a bit. When I came in I was a bit of a

mess. My eyes didn't open for a week (although I was always

quite conscious). They thought I had a fractured base (skull), but

I think the X-ray showed I didn't. My nose was bashed in, but

they've got the most marvellous Harley Street specialists out here~

who've joined up for the war as Majors.

Dahl's situation was so dire he was not expected to live or be able to see again; he credits this experience with a writing impetus. But he did recover and soon returned to the RAF, not as a pilot but as an officer in the British Embassy in Washington, D. C.. In this position, Dahl visited President Roosevelt's New York home, met Ernest Hemingway, and in a short story popularized the term "gremlin" (little goblins that wrought havoc on airplane engines.) He wrote his mother of every extraordinary meeting and doing as he slipped into a writer's habit.

After Sofie Magdalene died in 1965, Roald received her collection of letters, all tied up in green string, he was utterly surprised she had kept them:

My mother, for her part, kept every one of these letters, binding them carefully in neat bundles with green tape, but this was her own secret. She never told me she was doing it. In 1957 when she knew she was dying, I was in a hospital in Oxford having a serious operation on my spine and I was unable to write to her. So she had a telephone specially installed beside her bed in order that she might have one last conversation with me. She didn't tell me she was dying nor did anyone else for that matter because I was in a fairly serious condition myself at the time. She simply asked me how I was and hoped I would get better soon and sent me her love. I had no idea that she would die the next day, but she knew all right, and she wanted to reach out and speak to me for the last time.

From Roald Dahl's Boy

Donald Sturrock's Love from Boy: Roald's Dahl's Letters to His Mother is an essential selection of letters Dahl wrote to his mother, suggesting - though never showing directly because we lack her response - the magnificent character of Sofie Magdalene. Life is revealed in our letters to loved ones; when they are published for the world, the guilt of voyeurism is overcome by the absolute enlightenment of what our beloved artists and writers reveal. Like John Steinbeck's daily letters - some sent, some not - to his editor while writing East of Eden or Vincent van Gogh's abundant soul-bearing letters to his brother, Theo. And then there are the letters of John Keats, which, when published fifty years after his death, turned the neglected poet into a bit of a cult hero.