"We need to get a philosophical fingernail under the edge of the firmly stuck-down masculinity sticker, so we can get hold of it and rip it off."

My better angels do not always triumph, but in my bones, I do not believe in fighting anger with anger or toxicity with toxicity. Better to disarm than do battle. Neurologist and humanist Oliver Sacks once wrote that he pursued medicine to understand his schizophrenic brother. Sacks followed a "what it was like to be this person?" approach throughout his life of treating patients with neurological malfunctions that, in many ways, affected their personhood.

No one is undeserving of an empathetic gaze. (While that means kindness, it is not weakness.) In life and on The Examined Life, I attempt to apply that mentality to everyone, men, women, minorities, majorities - everybody.

Grayson Perry's (born in 1960) essay on masculinity and the male identity, The Descent of Man, is the intellectual embodiment of this mandate.

Grayson Perry at the 'Who Are You?', Display at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Grayson Perry at the 'Who Are You?', Display at the National Portrait Gallery, LondonI've handed a copy of The Descent of Man to many men I know and love. Men who are wonderful but contained by invisible masculinity. What follows might be uncomfortable if you are a man - especially a straight, white man - but I'm handing it to you because it matters to me, many people you know, and ultimately, to you.

Perry extends an arm of sympathy:

We need to get a philosophical fingernail under the edge of the firmly stuck-down masculinity sticker, so we can get hold of it and rip it off. Beneath the sticker, men are naked and vulnerable - human even.

No one enjoys looking into a mirror that reflects shortcomings. That gaze becomes disproportionately more difficult in matters as deep, personal, and sensitive as personal identity. But you must ask yourself, what happens when we don't? What do we lose if we fail to ask "what it was like to be this person?"

"Study for a Portrait" by Francis Bacon, 1952. Bacon's distortion of an unnamed man in suit is also entitled "Businessman." Learn more.

"Study for a Portrait" by Francis Bacon, 1952. Bacon's distortion of an unnamed man in suit is also entitled "Businessman." Learn more.Back to men and what we call "toxic masculinity," the idea that there are men who perpetuate masculinity at the expense of everything else. Perry calls it "Default man," which is less aggressive and addresses something profoundly true: the default setting of something is rarely seen or judged; it just is.

If a fish cannot see the water it is in, Perry makes invisible visible by throwing dye into the water:

The most pervasive aspect of the Default Man identity is that it masquerades very efficiently as 'normal' and 'normal,' along with 'natural,' is a dangerous word, often at the root of hateful prejudice. 'You and your ways are not normal' is a phrase often blatantly thrown in the face of oppressed minorities. The thinking behind such attacks is behind every decision that shapes the banal, everyday structures of our lives. We need to constantly call attention to these seemingly small injustices, for we may find, like turning off the humming extractor fan, that it seems dramatically more pleasant without the irritations we have become used to.

Sir Grayson Perry is the perfect male to tackle this issue. If Perry did not exist, I'm not sure we could invent him. He is an extraordinary Turner Prize-winning British artist who pushed ceramic art to new boundaries of expression and lives openly as a transvestite. He speaks the language of masculine males and the language of non-masculine males.

I am a transvestite; I am turned on by dressing up in clothes that are heavily associated with being female. This is perhaps some unconscious renunciation of being a man, or at least a fantasy flight towards femininity. I sometimes like to pretend I am a woman, so from a young age, I have felt that masculinity was optional for someone with a penis. Because I am a transvestite, people often assume this gives me a special insight into the opposite gender. But this is rubbish: how can I, brought up as a man, know anything about the experience of being a woman? It would be insulting to women if I did. If anything, it gives me a sharper insight into what it is to be a man.

Grayson Perry receives the Freedom of the City of London, 2015.

Grayson Perry receives the Freedom of the City of London, 2015.The complexity of Perry's relationship with masculinity is beyond sartorial and sexual. He celebrates his vulnerability, from his art to his personality-rich teddy bear (I have a fully-developed teddy bear too, and fell in love with my husband when I learned he did as well).

Our classic Default Man is rarely under existential threat; consequently, his identity has tended to remain unexamined. He ambles along blithely, never having to stand up for his rights or defend his homeland. What millennia of male power has done is to make a society where we all grow up accepting that a system grossly biased in favour of Default Man is natural, normal and common sense, when it is thing but. The problem is that a lot of men think they are being perfectly reasonable when in fact they are acting unconsciously on their own highly biased agenda. Any-Default Man feels he is the reference point from which all other values and cultures are judged. He might not be aware of it, but Default Man thinks he is the zero longitude of identities. He has forged a society very much in his own image, to the point where now much of how other groups think and feel is the same. They take on the attitudes of Default Man because they are the attitudes of our elders, our education, our government, our media. Default Man has had way too much say in the shaping of our internalized ideals. He has shaped the idealized selves we all try to live up to into versions that fit in with his needs.

Back to the fish/water analogy: Perry dyes the water so we can see it; he doesn't drain the tank. He does not want to diminish men for sport, nor does he seek to banish masculinity from the premises. He wants us to see the water and choose whether it is what we want.

I wish I had this book years ago. When I was a McKinsey consultant ages ago, a firm partner (do I need to say he was male?) asked me what the firm could do to retain women. Quick as a flash, I said: longer paternity leave. It is an issue, of course, but I meant to make it ok for men to take on domestic responsibilities. By domestic, I do not mean house and family; I mean all the aspects of life that are not work, politics, or finance. Let's normalize men's roles outside the workplace as we have women's roles inside the workplace.

Despite all this, what the partner heard was "longer paternity leave." Just those words and that exact policy. Had I unloaded my heart and dyed the water, so to speak, it would have turned from a conversation of 'what I needed as a woman' to 'what he had to give up as a man,' which, in my experience, is the wall that men - men I love and adore - rarely surmount. Not consciously, emotionally, or practically.

What I would have said, had I more courage, is it is not about domesticity; it is about power. Men, I need your power. We all need your power. I do not want you to carve out a contained place for me; I need you to step aside and sit down, just like I have to step aside and sit down for people of color and others. There is not enough power for everyone, and the imbalance of it in the hands of men is the heart of Perry's essays:

One of the central issues here, and the reason this book is called The Descent of Man, is that as women rise to their just level of power, then so shall some men fall. The men who find themselves justifiably passed over or demoted will inevitably feel angry, they will be bearing the brunt of a very necessary corrective. They may rail against women but principally, they will be victims of their own unhelpful masculinity and a dominant elite of other men. Power is key. The nature of our leaders in politics, in the boardroom, in the media, in culture, and in the classroom, shapes how people think. The face of power is starting to give a better reflection of society, but a good likeness is still a long way off.

As Perry illuminates, there will be fear and loss, not simply power but of a fully-developed self of the Default Man. But my goodness, there can also be such tremendous gain! Do you feel trapped by the world's revered masculinity? Do you feel you need to act a certain way, or you won't get a job, a family, a house, or a life worth living? Are the systems you are making the best possible ways of doing things? Do you feel alone in your pain? What if Shakespeare had a sister would World War II have happened?

What I love about The Descent of Man is it respects men as humans, not objects, who want the best and strive to get it.

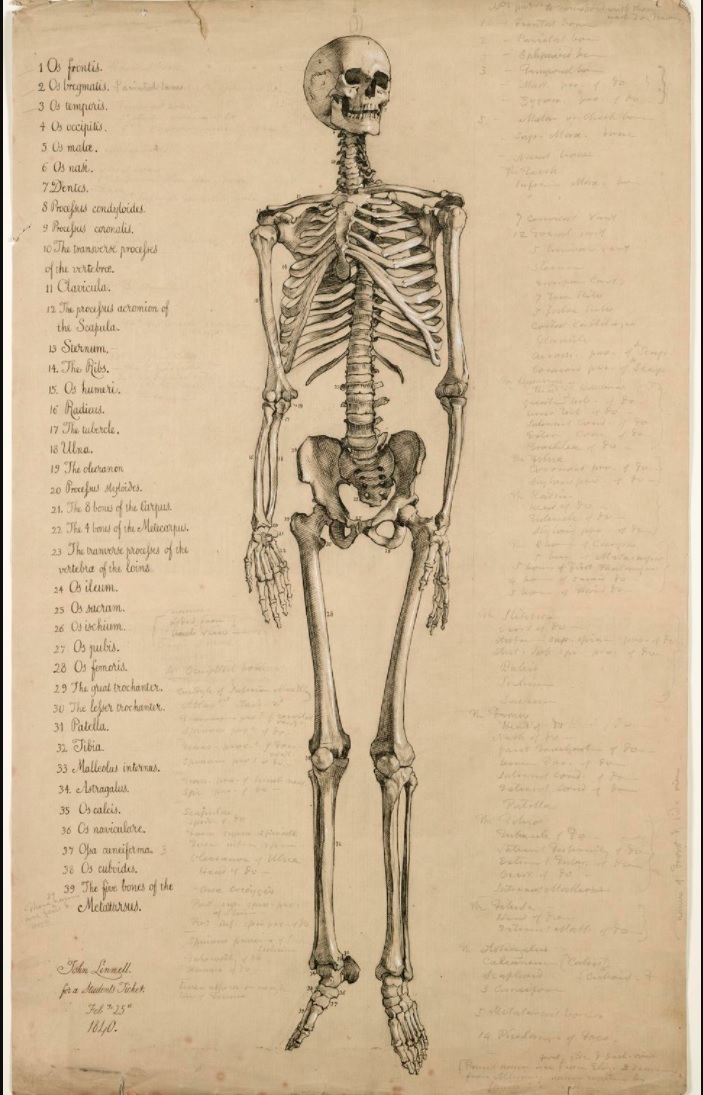

A pen and ink human skeleton drawing attributed to John Linnell (1792-1882), a British portrait and landscape artist. The sketch would have been used for scientific and medical accuracy (although inaccurate) rather than aesthetic purposes. Source: The British Library.

A pen and ink human skeleton drawing attributed to John Linnell (1792-1882), a British portrait and landscape artist. The sketch would have been used for scientific and medical accuracy (although inaccurate) rather than aesthetic purposes. Source: The British Library.As Perry says - and he means tongue-in-cheek to the fact that we often think otherwise - men are human.

We need to get a philosophical fingernail under the edge of the firmly stuck-down masculinity sticker, so we can get hold of it and rip it off. Beneath the sticker, men are naked and vulnerable - human even. It is a newsroom cliché that masculinity is always somehow 'in crisis', under threat from pollutants such as shifting gender roles, but to me, many aspects of masculinity seem such a blight on society that to say it is in crisis is like saying racism was in crisis' in civil-rights-era America. Masculinity needs to change. Some may question this, but they are often white middle-class men with nice jobs and nice families: the current state of masculinity is biased in their favour. What about all the teenagers who think the only manly way out of poverty and dysfunction is to become a criminal? What about all the lonely men who can't get a partner, have trouble making friends, and end up killing themselves? What about all the angry men who inflict their masculine baggage on the rest of us? All of us males need to look at ourselves with a clear eye and ask what sort of men would make the world a better place, for everyone.

To look with a clear eye requires we act as a community. Without superiority but with kindness. And it is relevant for everyone to ask: do you know what it is like, truly like, to be this other person? A female? Or Black person? An immigrant or a white male? We all know something about what it means to be X identity more than another does. The best any of us can do is take responsibility for seeing things we cannot see and then acting on that knowledge in a way we would want others to act towards us.

The Examined Life is a safe space for imperfection, Default Men and otherwise. I have built an imagined community of people who inhabit that space, like Steinbeck, a massively masculine male who never allowed his identity to blind his empathy, nor his vulnerability; or Andy Warhol's life-long struggle to exist as he truly was; poet Robert Lowell's howl of hidden mental illness. As you consider Virginia Woolf's thoughtful question what if Shakespeare had a sister?; and press your better self through Thích Nhất Hạnh's soul-mending wisdom on dealing with anger, I want to assure you that if you respect the process of knowing the thing unknown to you, this Site is for you. And you are not alone.