"I always enjoy taking a bird's-eye view."

"Everyone has a bird story," birder, poet and biologist J. Drew Lanham reminds us in his poetic avian collective. For many of us, our bird story is unwritten or unintelligible. Birds passerine through our magpie lives daily. And then suddenly, when you least expect it, your bird story will arise in the most spectacular, lucid way and soar irretrievably into your heart and mind.

Author Helen Macdonald assuaged her body-numbing grief by learning to train a goshawk, stepping into its existence, and feeling its needs so deeply and reverently that they usurped her own. Or Jon Day, whose pigeon training and racing expanded the metaphor of home and home-making when he sought the same in his life. Joy Davidman evoked a sparrow in her love sonnets to C. S. Lewis, and, of course, Ted Hughes used a crow to express his darkest, unforgivable self. Birds have visible habitats and invisible mindsets. Their delicate bodies are equally by fierce personal bonds. Birds are us in some parallel existence. Or are we birds?

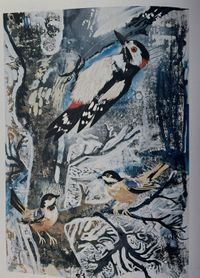

"Winter Woodpecker" is an artistic response to "the first serious snow of winter." Collage by Mark Hearld.

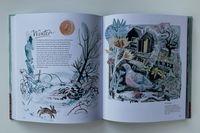

"Winter Woodpecker" is an artistic response to "the first serious snow of winter." Collage by Mark Hearld.Everyone has a bird story. Sometimes, those stories write a book. Artist Mark Hearld, an exceptional creative force whose joyful making is a byproduct of expansive chaos and tasteful discrimination, has such a book. Through ink and gouache, linocuts, lithographs, and raucous collages, Hearld's Workbook thrusts us into a world of meaningful objects, reimagined known spaces and birds, birds, birds that sing, sing, sing.

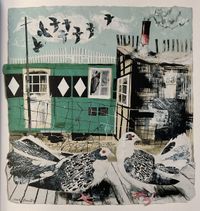

"Whitby Pigeon Loft," 2001, collage. Photograph by Doug Atfield.

"Whitby Pigeon Loft," 2001, collage. Photograph by Doug Atfield.The visual delight of this book includes many of Hearld's well-developed art forms, including linocutting, which is cutting into a linoleum block and then rolling layers of paint on the cut piece. The result is smooth, layered, and graphic.

In its simplest form, linocutting is about black and white. The image is created by removing areas of surface that you do not wish to print. The composition is determined by tonal counterpoint, that is, black against white, white against black. Success with the medium is achieved through a subtle application of contrasts; intricate patterned marks provide a foil for bold expanses of ink. White paper comes to life with the residual, inked-up marks left by the cutting tool. Picasso and Bawden demonstrated a masterly grasp of the medium, the former for the animation in each image, the latter with his command of decorative patterns.

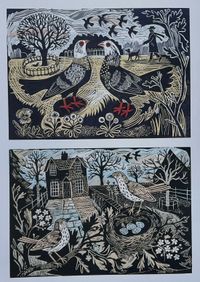

"Ballingdalloch Blackbird," a linocut print made by Hearld in Scotland. This image was published by St. Judes Press.

"Ballingdalloch Blackbird," a linocut print made by Hearld in Scotland. This image was published by St. Judes Press. "Pigeons in the Park" (top) and "Thrushes' Nest (below) are both multi-block linocuts made in 2007 for an exhibition on artists Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious.

"Pigeons in the Park" (top) and "Thrushes' Nest (below) are both multi-block linocuts made in 2007 for an exhibition on artists Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious.

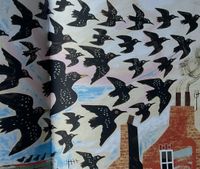

Hearld writes: "'Birds from 'Flight X', originating as gifts to friends, culminated in a series of birds reworked in color and pattern until they met the imaginative ideal."

Hearld writes: "'Birds from 'Flight X', originating as gifts to friends, culminated in a series of birds reworked in color and pattern until they met the imaginative ideal." "The Quince Tree" is my favorite for the utter wildness of the allotted space and the birds' happiness therein.

"The Quince Tree" is my favorite for the utter wildness of the allotted space and the birds' happiness therein.The vernacular of location, as Hearld names it, is the detail of space immediately outside his door and studio. The farms, fields, lanes, small holdings, and York city walls. The inherent color in the landscape, air, and the atmosphere.

The seaside brings back memories of childhood holidays: beady-eyed herring gulls up close or taking chips from your hand in flight; the saltiness of Edward Ardizzone's Little Tim books; found treasures picked up on the beach, a feather, a broken shell, a piece of glass dulled by the tide. The otherness of the seashore is rich in inspiration. The natural palette of sand and sea contrasts beautifully with the high color of the plastic flotsam and jetsam washed up on the shore. Fishermen's huts and grounded boats, shingle, and rock pools all offer endless creative opportunities to explore.

"On the Harbour Pottery Roof." Hearld explains: "The Chinese Chippendale-style roof lantern on top of the harbourside poetry in Whitby... A flag billows and raucous gulls cavort."

"On the Harbour Pottery Roof." Hearld explains: "The Chinese Chippendale-style roof lantern on top of the harbourside poetry in Whitby... A flag billows and raucous gulls cavort."

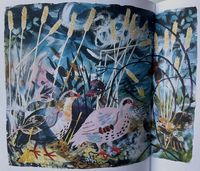

"Autumn Partridges" captures the "defined point" of early September.

"Autumn Partridges" captures the "defined point" of early September. "Black Swan" collage. "For this collage made outside the banks of mill race at Buttercrambe, North Yorkshire, I used a piece of Curwen Press endpaper designed by Sarah Nechamkin in the 1940s."

"Black Swan" collage. "For this collage made outside the banks of mill race at Buttercrambe, North Yorkshire, I used a piece of Curwen Press endpaper designed by Sarah Nechamkin in the 1940s." "St. Paul's Pigeons" is a small collage commissioned by St. Judes for an exhibition in 2009.

"St. Paul's Pigeons" is a small collage commissioned by St. Judes for an exhibition in 2009. "Starlings". This somewhat treacherous bird, Hearld admits, "Is one of my favorites. Its spotted, iridescent plumage and cheeky antics are a delight to observe in the heart of the city."

"Starlings". This somewhat treacherous bird, Hearld admits, "Is one of my favorites. Its spotted, iridescent plumage and cheeky antics are a delight to observe in the heart of the city." Collage work based on the landscape transformation of snow.

Collage work based on the landscape transformation of snow.Other than collages that seem to form themselves from scrapes of paper and barely dry paints, Hearld's most beloved art form is the lithograph. It is a centuries-old art form (although it has modernized) that involves multiple materials and the close interaction between layers of color.

I have long admired the quality of lithography; its capacity for nuanced, tonal washes is unique in printmaking. Before I'd ever made a lithograph, people said to me that my work seemed akin to the School Prints of the 1940s. I became a fan of images by John Nash and Julian Trevelyan and Barbara Jones's Fairground (1946), a copy of which hangs on my stairs; I also own two John Piper lithographs. My interest in mid-twentieth-century artist-designers gave me a familiarity with the auto-lithographic process used by the Curwen Press and the printer W.S. Cowell. I was invited to try out lithography at the Curwen Studio, and the sight of my image on press for the first time still has a certain magic.

"Minster and Magpies" lithograph inspired by a long walk in late May along the York City wall. Photograph by Doug Atfield.

"Minster and Magpies" lithograph inspired by a long walk in late May along the York City wall. Photograph by Doug Atfield. "Barred Cockerel" collage.

"Barred Cockerel" collage. "Twilight" collage, inspired by Hearld's desire to "capture the half-light."

"Twilight" collage, inspired by Hearld's desire to "capture the half-light."I have spared you the full flutter of plumage scattered on these sumptuous pages, but do seek out Mark Hearld's Work Book should you want a visual, sensual assumption of material, beauty, and place. Hearld is an abundant talent, a constantly working artist who shapes the things we see daily - and often miss - into art. Read more from Ursula Le Guin on the well-spring of creativity, Toni Morrison on stillness as art, the ways we form things piece by piece, and poet Mary Ruefle on the invisible everything that is human imagination.