"The world is better, finer, because he lived in it."

What do we owe the past? What do we give to those who kneeled on these shores and now tower on plinths? Gratitude? Honor? Do we owe them our judgment? Humility?

First and foremost, we must remember them as humans, which can be pretty unnerving.

"If you were to have a conversation with my father," Martin Luther King, III once asked Toni Morrison (February 18, 1931 – August 5, 2019), "What would you like to ask him?" Allowing an option of possibilities, the "shared investigation of dialogue" as Borges once called it, Morrison admitted her primary response would be all-encompassing self-doubt.

"Oh, I hope he is not disappointed. Do you think he's disappointed?" Morrison replied to the Reverend's eldest son, "I hope he is not disappointed in me." Her concern is so interesting since Morrison never met King nor had any personal relationship with him.

My memory of him is print-bound, electronic, through the narratives of other people. Yet I felt this personal responsibility to him. He did that to people. I realized later that I was responding to something other and more durable, than the complex personhood of King.

And yet what she said rings true: I hope he's not disappointed in me.

There is something indelibly human about King and his legacy. He died so young; his words were tender, and his resolute invincible. Although he exists in reverie to many of us, holding this day - the third Monday of the first month of the year - still in time begs us year after year to ask why. Who was King, and why does this day exist? We cannot escape that he lived and died; ultimately, we all must stand before him on this day and ask: Have I done enough?

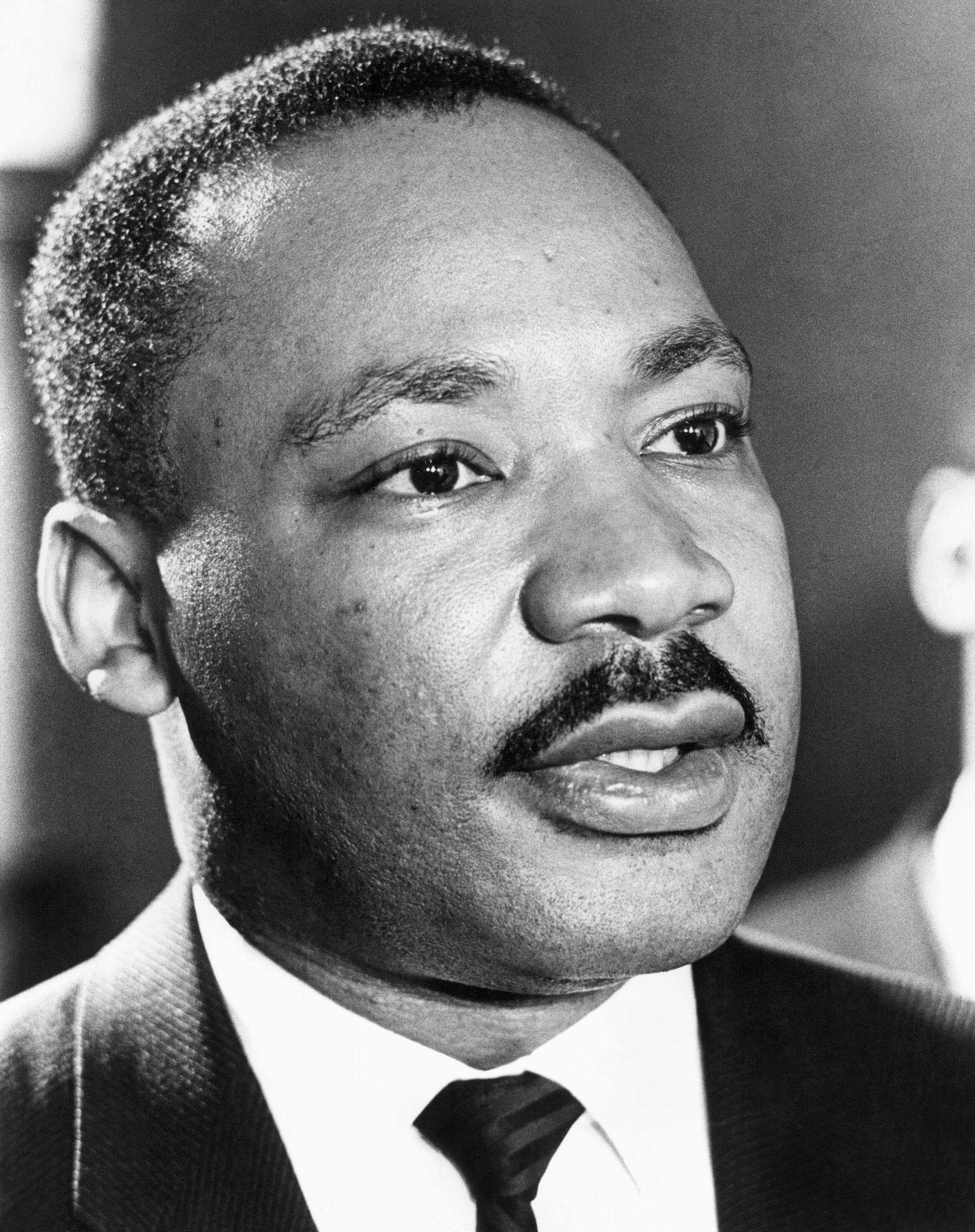

Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1965.

Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1965.Morrison, who was two years and a month younger than King, responded to the question asked by his kin in a poignant essay, "Tribute to Martin Luther Ling." She thrusts aside anxiety and focuses on the eternal question of all civil rights movements: when will there ever be an arrival? An end?

I have never lived, nor have any of you, in a world in which race did not matter. Such a world, a world free of racial hierarchy, is frequently imagined or described as a dreamscape, Edenesque, utopian so removed are the possibilities of its achievement. [...] The race-free world has been positioned as ideal, millennial, a condition possible only if accompanied by a Messiah or situated in a protected preserve, rather like a wilderness park.

Toni Morrison was a generous and righteous genius who reminded us of our innate capacity to create otherness and how to react to chaos with stillness. But on her shoulders was this tremendous weight to carry the past into the future, this unbearable burden of witness. A weight bigger and grander than any of us realize. Or carry.

Faces might be etched in stone, but rights are not.

American poet Maya Angelou - a writer who memorably emphasized the writer's responsibility to improve humanity and craft - said she met King when she was the New York coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She recalled his kindness when he stepped aside to comfort her and noticed a deep, resonating sadness. Morrison never met King, yet she, much like Angelou, "felt this personal responsibility to him."

A responsibility to Dr. King personally and all he dreamt and achieved.

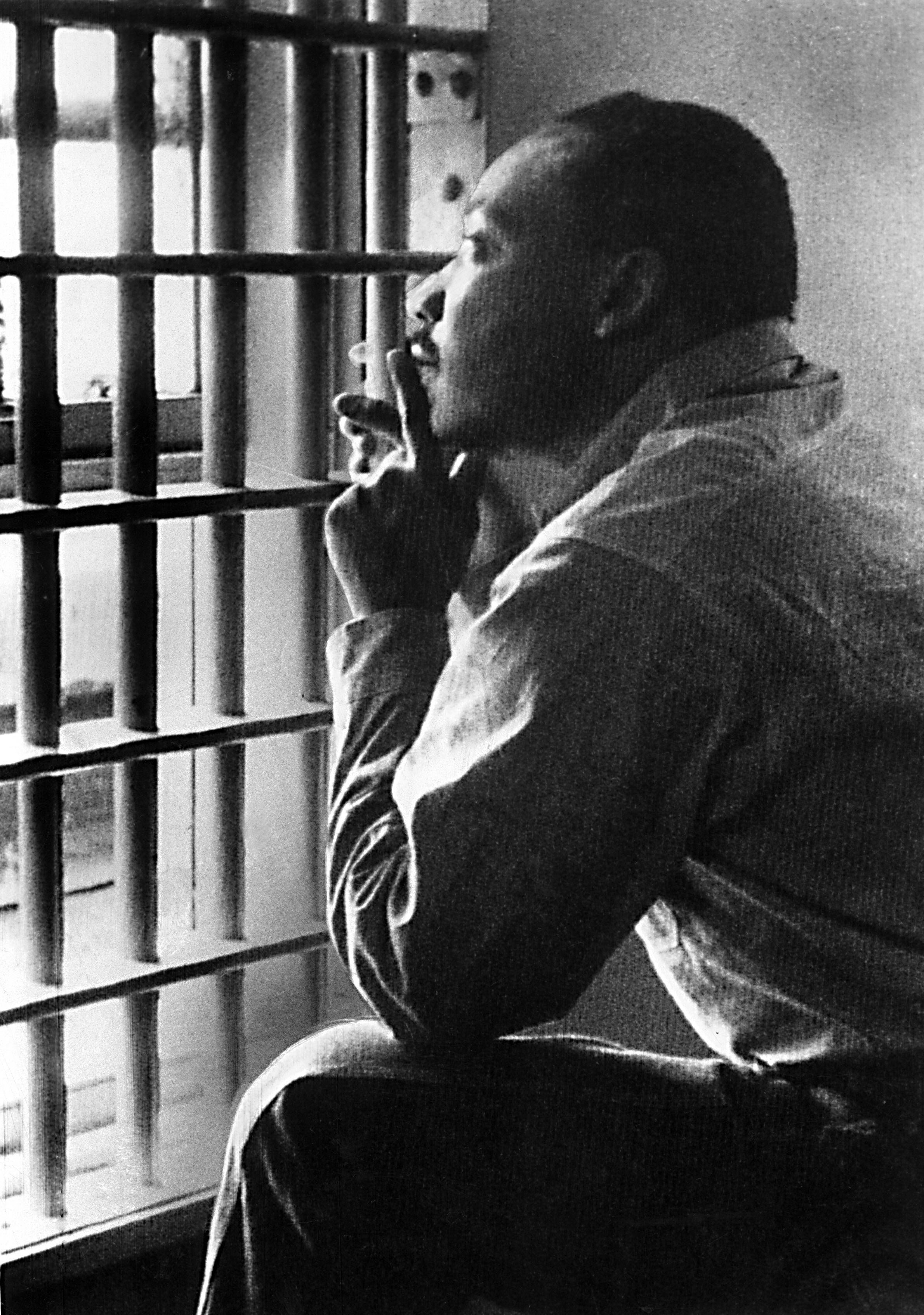

Martin Luther King, Jr. in the Jefferson County Jail, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963. Source: Everett/CSU Archives.

Martin Luther King, Jr. in the Jefferson County Jail, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963. Source: Everett/CSU Archives.During Dr. King's incarceration for a disruptive but peaceful Birmingham protest (he was arrested for failure to comply with a court-ordered injunction against “boycotting, trespassing, parading, picketing, sit-ins, kneel-ins, wade-ins, and inciting or encouraging such acts”), he penned one of the most significant statements on civil rights and the nature of change ever written.

"You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham," wrote King to clerical leaders who had called on him to pursue legal means rather than civil disobedience. "But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations."

I wish you had commended the Negro sit-inners and demonstrators of Birmingham for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer, and their amazing discipline in the midst of great provocation. One day the South will recognize its real heroes. They will be the James Merediths, with the noble sense of purpose that enables them to face jeering and hostile mobs, and with the agonizing loneliness that characterizes the life of the pioneer. They will be old, oppressed, battered Negro women, symbolized in a seventy-two-year-old woman in Montgomery, Alabama, who rose up with a sense of dignity and with her people decided not to ride segregated buses, and who responded with ungrammatical profundity to one who inquired about her weariness: My feet are tired, but my soul is at rest... One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters, they were in reality, standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great swells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

From Martin Luther King's Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Morrison died in 2019, and it makes me think of something short-story writer Lydia Davis once wrote: "105 years old: she wouldn't be alive today even if she hadn't died." King, had he lived, would have turned 94 in 2023. Had he not died, he might have still been alive today. Could you stand in front of him?

His confidence that we were finer than we thought, that there were moral grounds we would not abandon, lines of civil behavior we simply would not cross. That there were things we would gladly give up for the public good, that a comfortable life, resting on the shoulders of other people's misery, was an abomination this country, especially among all nations, found offensive.

When King died in 1965, he left that tremendous courage and personal moral ground to others to carry. Faces might be etched in stone, but rights are not.

Where does that leave us? Where did that leave Morrison?

Toni Morrison in 2008.

Toni Morrison in 2008.What burdens do we carry when we hold the memory of others? It is imperative to imagine a human who embodies such purpose under the skin, under the nails, and in the grime of the ear.

Morrison reflects on King's imagined presence:

I know the world is better, finer because he lived in it. My anxiety was personal. Was I any better? Finer? Because I have lived in a world that is imaginary. Would he be disappointed in me? The answer isn't important. But the question really is, and that is the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. He made the act of assuming personal responsibility for alleviating social harm ordinary, habitual, and irresistible. My tribute to him is the profound gratitude I feel for the gift that his life truly was.

Toni Morrison died in 2019, aged eighty-eight. In 2023, the U. S. Postal Service announced that Toni Morrison's likeness would appear on the postage stamp. It is a physical nudge to ask why she holds that space and whether we have done enough to stand in her shadow. Every time we send a note. She deserves that. And more.

If you could bow before Morrison or King or perhaps ask them anything, what would it be? Would she be proud of you? Would he?

Morrison's The Source of Self-Regard is a collection of warm, strong, effortless essays including the novelist's hopeful benediction to young graduates and stillness as art in times of chaos.