"Everybody struggles with asking."

—Amanda Palmer

If December is the season for giving, what is the season for asking? Let’s outstretch our hands and make space for our needs.

Please help. Please notice. Please pick up my shattered pieces and carry me for a step…

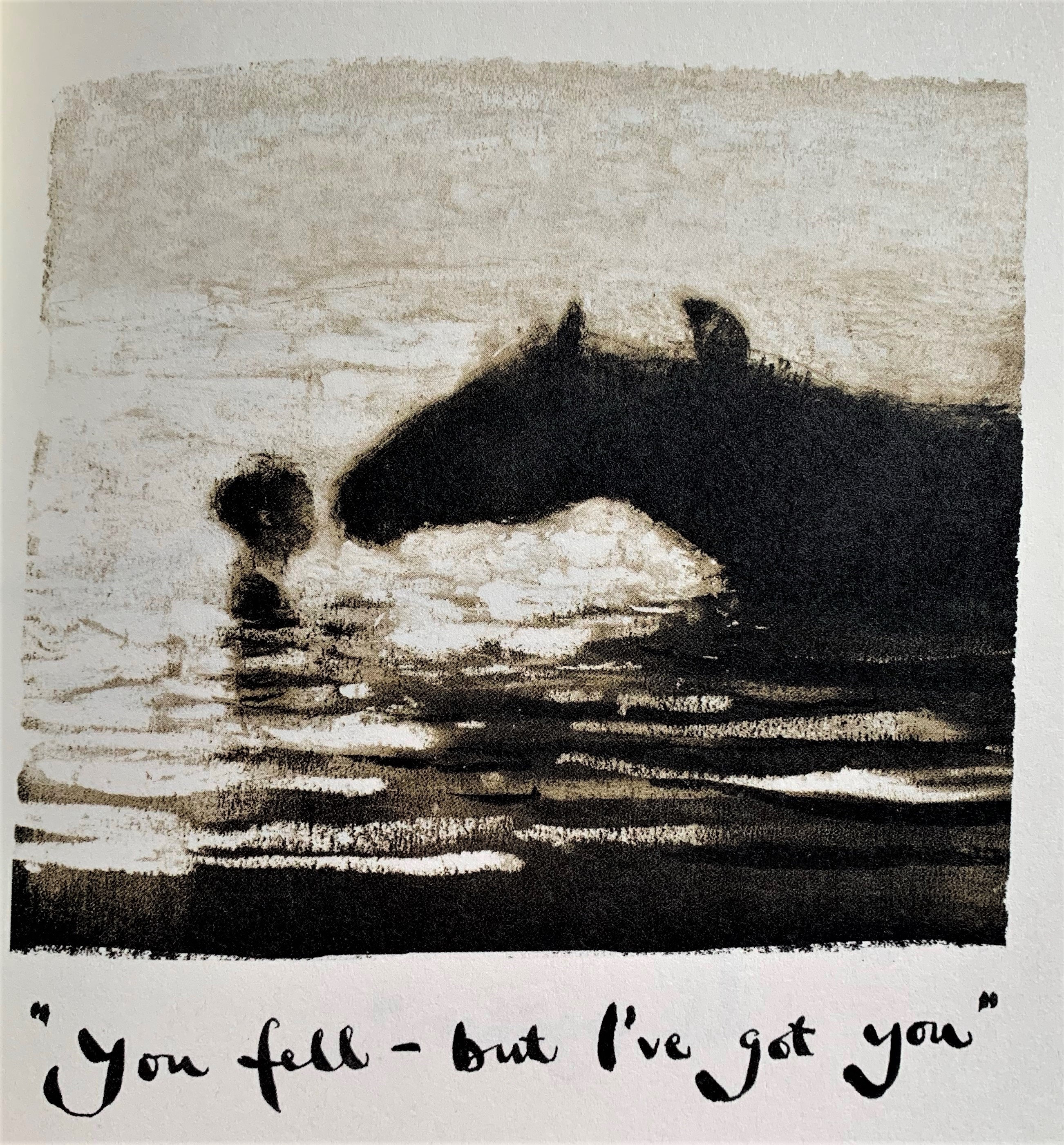

“You fell – but I’ve got you.” from Charlie Mackesy’s The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse.

“You fell – but I’ve got you.” from Charlie Mackesy’s The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse.For years, musician Amanda Palmer dressed as a statue bride near Harvard University campus to supplement her artistic income. Completely still. She came to a brief life when a passerby gave her a buck.

Almost every important human encounter boils down to the act, and the art, of asking. Asking is, in itself, the fundamental building block of any relationship. Constantly and usually indirectly, often wordlessly, we ask each other—our bosses, our spouses, our friends, our employees—to build and maintain our relationships with one another.

Will you help me?

Can I trust you?

Are you going to screw me over?

Are you suuuure I can trust you?

And so often, underneath it all, these questions originate in our basic human longing to know: Do you love me?

From Amanda Palmer’s The Art of Asking

Palmer perforates the thick space between herself and strangers, if only briefly.

I imagine young Ernest Hemingway when he stepped into Gertrude Stein’s Paris apartment and asked the established writer to review his stories.

She said that she liked them except one called ‘Up in Michigan.’ ‘It’s good,’ she said. ‘That’s not the question at all. But it is inaccrochable. That means it is like a picture that a painter paints and then he cannot hang it when he has a show and nobody will buy it because they cannot hang it either.

From Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast

As an editor, T.S. Eliot gave succor to a young, extremely talented Marianne Moore, persuading Moore to publish a collection of poems, though she doubted her ability.

Years later, Eliot also met the outstretched hands of Denise Levertov — the British-American poet who, at the age of twelve, sent poems to the American-British poet, Eliot, who replied with a two-page type-written letter of encouragement.

I imagine his largess owed to his own need; Eliot had two open palms early in his career. Fellow poet Ezra Pound cobbled together a “Bel Esprit” fund to support Eliot as a full-time poet. Hemingway donated.

I think of President Ulysses S. Grant at the end of his life. Former President and General, yes, but of late, a failed businessman with failing health. He happened to throw some memoir notes by his acquaintance Mark Twain, who immediately became involved when he realized Grant was floundering. Not only did they form a deep friendship, but Twain edited and published Grant’s superb memoirs and earned both men a reasonable sum of money.

Palmer reminds us: “Everybody struggles with asking.”

Or consider the righteous James Baldwin, who had left America’s feckless social laws and ingrained bigotry to settle in Paris but who was persuaded (Baldwin’s words) by his childhood friend editor Sol Stein to return to America and pen ten critical essays that became Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son.

I don’t remember Baldwin’s resistance to doing the book but I do remember the editorial process, helped by recently finding my line-by-line editorial notes and Baldwin’s responses, which are included in the correspondence section of the book. Writers can be wary of editors they don’t know well. By the time Baldwin and I had to deal with Notes of the Native Son, the overlay of a friendship of a dozen years made the process easier.

From Sol Stein’s Native Sons

And then there is my beloved Henry David Thoreau, who went to “live simply” but could only do so on his friend Emerson’s land (I learned that fact from Amanda Palmer).

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a letter of encouragement to Walt Whitman after Whitman’s epic poem "Leaves of Grass” was poorly received. And all three of these cosmic marvels, in some way, influenced poet Mary Oliver two centuries later in poetry, in mind, and in her endless quest to sit in eternity.

We all have a deep, unspoken desire to be seen, to connect. At various points in our lives, we want someone to tell us, “I see you. You embodied spirit. You matter.”

We want to say those words to others.

Palmer reminds us: “All humans… want to be seen; it’s a basic need.”

Of course, this brings me to Rilke. Although his poetry can satiate any appetite for profoundness, Rainer Maria Rilke is well-known today for a series of letters he wrote to an aspiring poet, Franz Xavier Kappus, who reached out to Rilke in hopes of guidance.

Your letter only reached me a few days ago. Let me thank you for the great and endearing trust it shows. There is little more I can do, I cannot go in the nature of your verses, for any critical intention is too remote from me. There is nothing less apt to touch a work of art than critical words: all we end up with there is more or less felicitous misunderstandings. Things are not all as graspable and sayable as we are led to believe on the whole.

Excerpt from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to Franz Xavier Kappus

In response to this great, endearing trust handed to him, Rilke corresponded with Kappus for a decade, providing gentle thoughts and subtle illumination.

You ask whether your verses are good. You ask me that. You have asked others, before. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other poems, and you worry when certain editors turn your efforts down. Now (since you have allowed me to offer you advice) let me ask you to give up all that. You are looking to the outside, and that above all you should not be doing now. Nobody can advise you and help you, nobody. There is only one way. Go into yourself.

“Virginia Woolf is my teacher,” admits American memoirist and narrator of our deepest notions of self, Dani Shapiro.

I keep her near me in the form of her A Writer’s Diary. I flip open the book to a random page and encounter a kindred spirit who walked this road before me, and who—though her circumstances were vastly different from my own—makes me feel less isolated in the world.

From Dani Shapiro’s Still Writing

I feel less isolated when I read John Steinbeck’s journals. I open them often, asking for something. I sigh at his sorrow and self-doubt.

Ultimately, that is what we seek with outstretched hands. Not answers, resources, or avenues to greatness, but rather to announce ourselves and be seen. To connect and commune.

What if we did this more? What if we met each other through this essential human need? Rather than affiliations based on geography, opinions, or accomplishments?

What might happen?

I want to close with a quick note on a beautiful relationship.

In his considered book about our death anxiety, psychologist Irvin D. Yalom expresses gratitude towards his mentor, Rollo May: “Rollo May mattered to me as an author, as a therapist, and finally, as a friend.”

May was one of the foremost psychologists and authors of the 20th century, known for augmenting the discipline with a philosophical concept of “being.” Yalom was inspired by May’s words and aligned his career with May’s thinking.

Their relationship, initiated by Yalom’s request for professional guidance, was always characterized by May assisting the younger Yalom. As May aged and deteriorated in body and self, Yalom stepped into a more supportive role, eulogizing the great man and speaking his memory to the world.

Go on. Stretch your fingers and lift your palm. Extend your arm in a long, raised line. Breathe deeply and exhale. Now for the tricky bit: stand there. With your hand open.

For as long as it takes.