"If a sense of humour were simply the ability to laugh, everybody would have a sense of humour."

"When I first came to England, I was struck by the English," wrote Gyorge "George" Mikes (pronounced Mee-KESH) in his shrewdly humorous classic How To Be a Brit. "Their outlook on life, their humour, their phlegm, their affected and real superiority, their insularity and aloofness from the rest of the human race."

John Cleese in the "Ministry of Silly Walks" sketch for Monty Python.

John Cleese in the "Ministry of Silly Walks" sketch for Monty Python."Their impact on me was overwhelming," wrote this Hungarian-born journalist who travelled to London in 1937 to cover pre-war events and decided to stay. From 1946 until 1980, Mikes published a wildly successful series of books, including English Humour for Beginners, which functioned as both a loving interpretation of the cultural character and a critical assessment of culture's insularity and hypocrisy.

National character, like individual character, is partly inherited, partly formed by the environment. Whether one or the other plays a greater part in character formation, and what the exact ratio is, need not concern us here. As the circumstances - the environment - of the British have changed since the war, the national character has also changed. The three events of the last forty years in the history of Britain were: the winning of the war, the loss of the Empire and the shift in the power structure in British society.

As humans use language as a means of self-expression and self-understanding, many of our psychological upheavals will affect language. Mikes argues that the result of these events on the national psyche was to construct a form of self-understanding through humour.

What we commonly (lovingly?) call 'British Humour' has three major components:

Laughing at Yourself

If a sense of humour were simply the ability to laugh, everybody would have a sense of humour... But a sense of humour, I believe, really begins when one is able to laugh at oneself. That's where a sense of proportion - something useful and positive - comes in. The person who can laugh at himself sees himself (more or less) as others see him. He can smile at his own misfortune, folly and weakness. He may even be able to accept the idea that in a disagreement the other person, too, may have a point.

Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry from "A Bit of Fry and Laurie" sketch comedy series, which ran from 1987-95.

Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry from "A Bit of Fry and Laurie" sketch comedy series, which ran from 1987-95. The concept of laughing at oneself in a more mild sense could be known as humility and is a key component of social connections and self-comfort. It was even named a pillar of joy by the inimitable Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu:

When we learn to take ourselves slightly less seriously,” the Archbishop continued, “then it is a very great help. We can see the ridiculous in us. I was helped by the fact that I came out of a family who did like to take the mickey out of others, and who were quite fond of pointing out the ridiculous, especially when someone was being a bit hoity-toity. And they had a way of puncturing your sense of self-importance."

From Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama’s The Book of Joy

A second aspect of humour is understatement - a means of communicating by miscommunicating. It is a concept that undermines our interpretation of things as they are to make possibly horrid things more innocuous.

Understatement

Understatement is not a trick, not a literary device: it is a way of life. It is a weltanschauung, i.e. a way of looking at the world. You have to breathe the air of England, and live with these understanding, tolerant - some say sheepish - people for a while before you get it into your blood. Unless you learn what understatement is you have not made even the first step towards understanding English humour. Life is one degree under in England and so is every manifestation of life.

[...]

The London Evening Standard reported one day that Concorde had resumed its London - Bahrain service on a twice-weekly basis but had left Heathrow without one single passenger. When a British Airways spokesman was asked about this somewhat curious state of affairs he replied: 'We never expected the service to be overcrowded.'

"Good afternoon!" Illustration by Nicholas Bentley, published in George Mikes's How to Be a Brit, 1946.

"Good afternoon!" Illustration by Nicholas Bentley, published in George Mikes's How to Be a Brit, 1946.English, self-professed 'entertainer' Stephen Fry begins his second autobiography with a form of understatement to align himself with the reader.

I really must stop saying sorry; it doesn't make things any better or worse. If only I had it in me to be all fierce, fearless and forthright instead of forever sprinkling my discourse with pitiful retractions, apologies and prevarications.

From Stephen Fry's The Fry Chronicles

And finally, Mikes calls out the British sense of humour for its noted streak of cynical darkness:

Cruelty

British humour has a strong streak of cruelty. It is amazing that these seemingly gentle people deem certain things funny which horrify others. What is the explanation? That these gentle people are not so gentle after all? That the rest of the world is too squeamish? Or perhaps something more subtle and complicated? The first objection to this statement - that British humour is cruel - is the simple reply that all humour is cruel. The idea that humour is gentle and sweet and that the humorist, or even the man with a good sense of humour, is a nice and likeable chap is nonsense. Humour is always aggressive. On the lowest level we laugh, or at least giggle nervously, at the man who has slipped on one of those famous banana skins. Our 'sudden glory' is always connected with someone else's sudden discomfort or ignominy.

"I had to get up in the morning at ten o'clock at night, half an hour before I went to bed, drink a cup of sulphuric acid, work twenty-nine hours a day down mill, and pay mill owner for permission to come to work, and when we got home, our Dad and our mother would kill us, and dance about on our graves singing 'Hallelujah.'" Michael Palin in the Four Yorkshiremen sketch, satirizes our romance of memory.

"I had to get up in the morning at ten o'clock at night, half an hour before I went to bed, drink a cup of sulphuric acid, work twenty-nine hours a day down mill, and pay mill owner for permission to come to work, and when we got home, our Dad and our mother would kill us, and dance about on our graves singing 'Hallelujah.'" Michael Palin in the Four Yorkshiremen sketch, satirizes our romance of memory. Mikes published British Humour for Beginners in 1980; hence aspects of the book feel dated. It lacks the multicultural complexity of today's British society. But overall, the enduring nature of Mikes's writing captures what it means to view culture from the periphery.

Gyorgy "George" Mikes in 1960.

Gyorgy "George" Mikes in 1960. Mikes also captures a truth that echoes today: we use culture and its subsets, like humor, as a means to express, understand, and normalise changes in our society and ourselves.

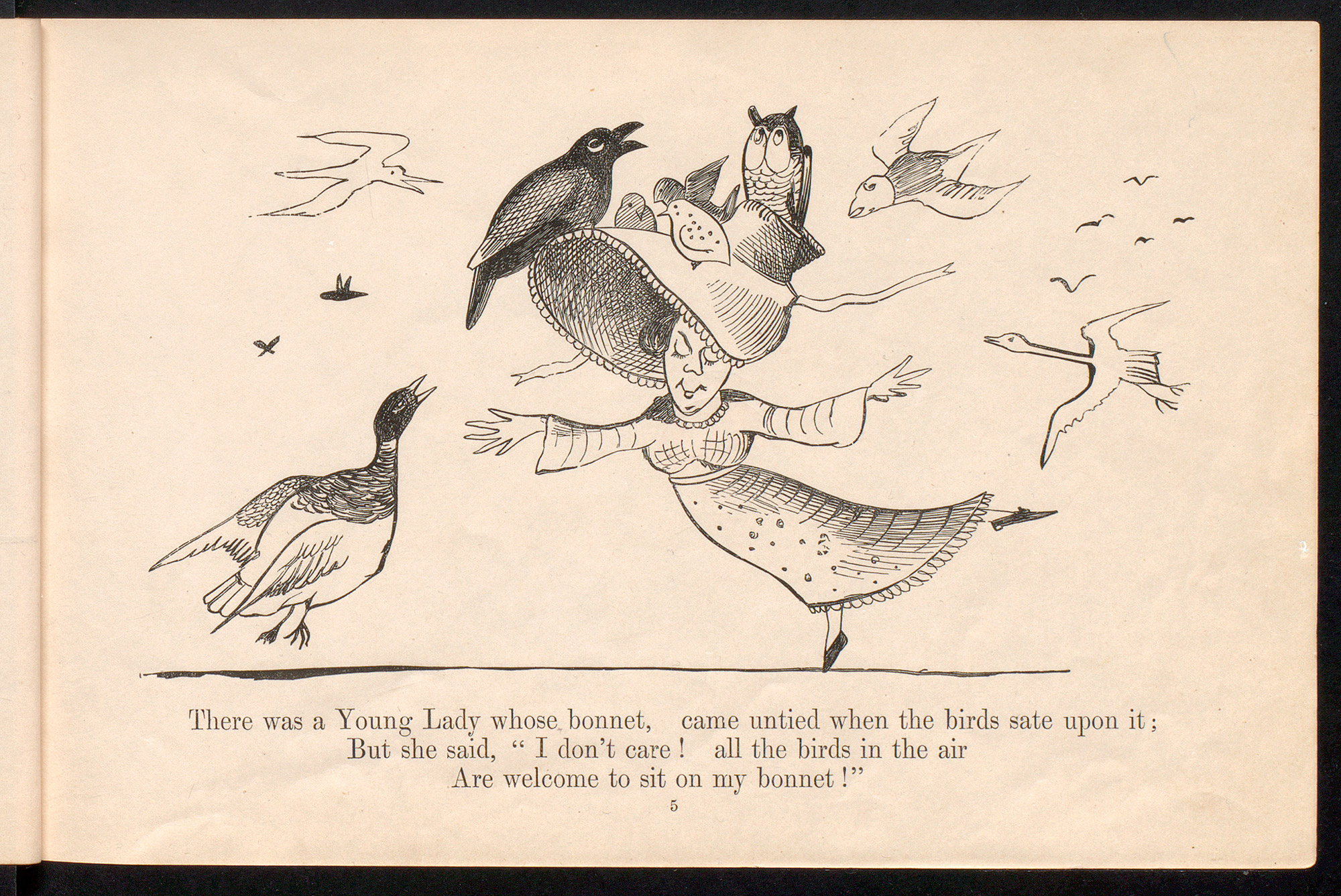

Recognise how recent this concept of 'British Humour' really is, with a look back to the 1900s when Edward Lear revolutionised humour through his nonsense poetry, a byproduct of the limerick poem that exists today in elements of absurdity (think Terry Gilliam's contributions to Monty Python). Lear was also a gifted illustrator and always paired drawn lines with imagined verse.

Edward Lear's illustration for his wonderfully original A Book of Nonsense, was published in 1861.

Edward Lear's illustration for his wonderfully original A Book of Nonsense, was published in 1861.“Lear’s nonsense poetry is not nonsensical poetry,” argues Mikes, “But poetical nonsense. It catches the imagination and often the heart; it amuses, it charms, and sometimes saddens the reader.”