"Illness is not a metaphor, and the most truthful way of regarding illness - and the healthiest way of being ill - is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphorical thinking."

Figurative language breaches the unsayable. "Metaphor is a way of thought long before a way of language," notes James Geary in his study of metaphor. "Metaphor systematically disorganizes the common sense of things...and it reorganizes it into uncommon combinations."

"I am now face to face with dying," wrote Oliver Sacks when he had terminal cancer, likening his illness to a mirror or a person.

Christopher Hitchens forms an even stronger metaphor: "When I described the tumor in my esophagus as a ‘blind, emotionless alien,’ I suppose that even I couldn’t help awarding it some of the qualities of a living thing."

"The Sick Child" by Edvard Munch, 1885. The first of six canvasses Munch painted over forty years. Each depicts his sister, who died from tuberculosis when she was fourteen. Munch also fell ill but survived. From the Børre Høstland - Nasjonalmuseet.

"The Sick Child" by Edvard Munch, 1885. The first of six canvasses Munch painted over forty years. Each depicts his sister, who died from tuberculosis when she was fourteen. Munch also fell ill but survived. From the Børre Høstland - Nasjonalmuseet.Although it extends our communicative abilities (of tricky subjects we usually want to avoid), metaphor is a fantasy, and, argues Susan Sontag (January 16, 1933 - December 28, 2004) in Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and its Metaphors invites understanding based on fantasy.

As long as a particular disease is treated as an evil, invincible predator, not just a disease, most people with cancer will indeed be demoralized by learning what disease they have. The solution is hardly to stop telling cancer patients the truth, but to rectify the conception of the disease, to de-mythicize it.

In her 1978 essay, Sontag studies the history of expression for two diseases: tuberculosis (of which her father died young) and cancer (of which Sontag died). She argues that far from aiding our communication, our figurative language obscures the reality of experience.

Metaphors appear when we lack proper words to describe what something is. "Death reigned in corners," wrote Daniel Defoe in 1722 about the devastating black plague. The likeness of the plague to a monarch (someone who reigns) is a powerful metaphor, but does it tell us what the victims suffered?

John Dunstall's 1666 broadsheet etching depicts nine scenes of the plague.

John Dunstall's 1666 broadsheet etching depicts nine scenes of the plague. Not only do metaphors fall short of communicating, argued Sontag, but they also miscommunicate.

Illnesses have always been used as metaphors to enliven charges that a society was corrupt or unjust. Traditional disease metaphors are principally a way of being vehement; they are, compared with modern metaphors, relatively contentless. ... Particular diseases figure as examples of conditions in general; no disease has its distinctive logic. Disease imagery is used to express concern for social order, and health is something everyone is presumed to know about. Such metaphors do not project the modern idea of a specific master illness, in which what is at issue is health itself.

Tying illness to social orders or worse, morality creates feelings of guilt and worthlessness in patients already suffering. Sontag gives us examples of this linguistic toxicity:

While TB takes on qualities assigned to the lungs, which are part of the upper, spiritualized body, cancer is notorious for attacking parts of the body (colon, bladder, rectum, breast, cervix, prostate, testicles) that are embarrassing to acknowledge. Having a tumor generally arouses feelings of shame, but in the hierarchy of the body's organs, lung cancer is felt to be less shameful than rectal cancer. And one non-tumor form of cancer now turns up in commercial fiction in the role once monopolized by TB, the romantic disease that cuts off a young life.

Sontag herself struggled with multiple occurrences of breast cancer. (For more on Sontag's death and reluctance to release her body to cancer, read Katie Riophe's excellent Violet Hour.)

Design for a memorial to poet John Keats, "Fates Seizing Keats," by Joseph Severn, 1822. © Harvard University

Design for a memorial to poet John Keats, "Fates Seizing Keats," by Joseph Severn, 1822. © Harvard UniversityWhen I think about the metaphors we used for COVID-19,

It is a study in volume. Why is that?

Loneliness significantly increases the anguish of dying. Too often, our culture creates a curtain of silence and isolation around the dying. In the presence of the dying, friends and family members often grow more distant because they don't know what to say. They fear upsetting the dying person. And they also avoid getting too close for fear of personally confronting their death.

This everyday isolation works two ways: not only do the well tend to avoid the dying, but the dying often collude in their isolation...Such isolation compounds the terror.

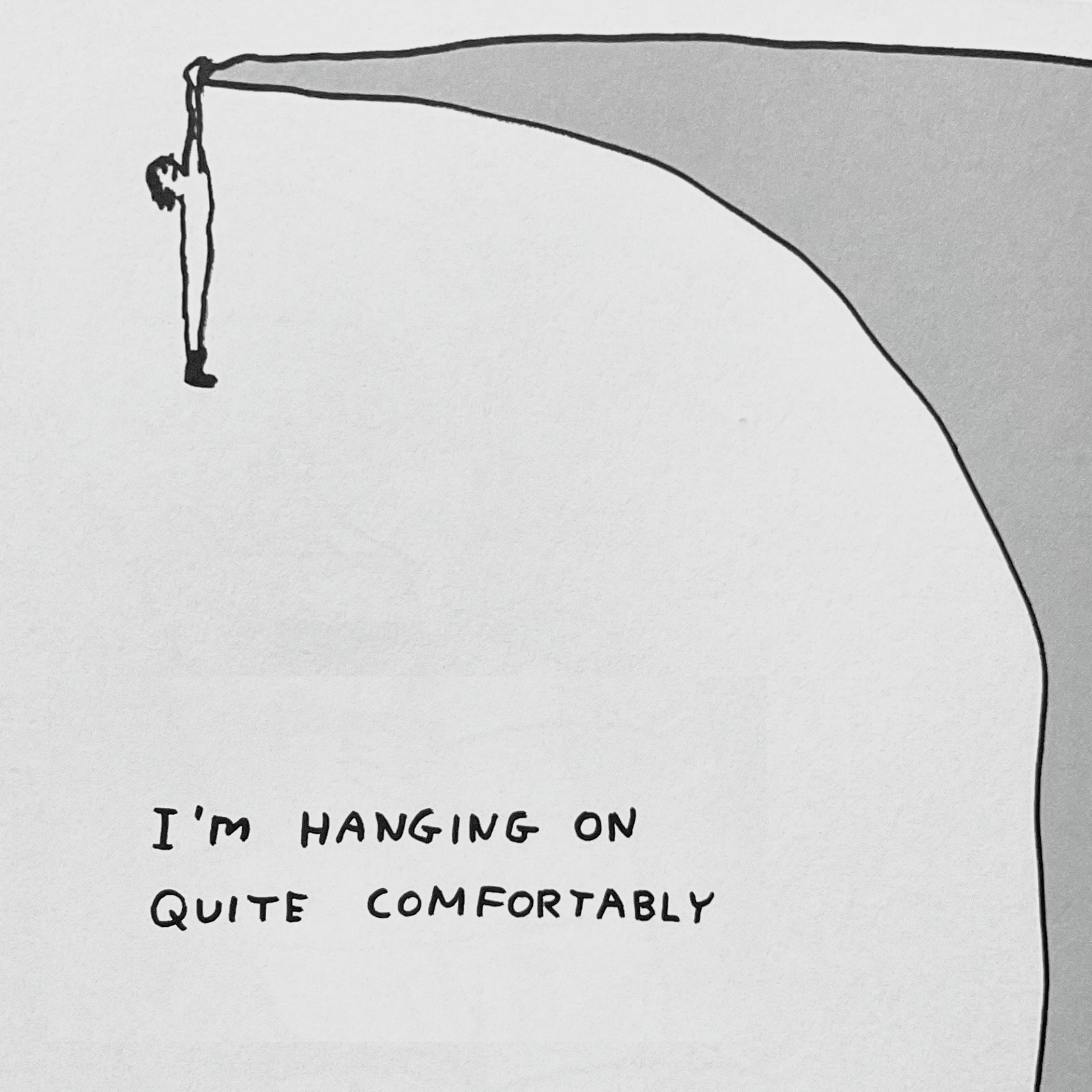

"I'm hanging on quite comfortably" from David Shrigley's perfectly absurd and completely accurate visual metaphor of humankind.

"I'm hanging on quite comfortably" from David Shrigley's perfectly absurd and completely accurate visual metaphor of humankind.Language precision is fundamental to our connection and communion with one another. Novelist Doris Lessing wrote something rather brilliant (about cats, but still) and how she sits down to be with them, to cross the divide that separates them.

Ultimately, language - imprecision or otherwise -is not what separates us; it is the conversation or lack thereof. The "sitting down to be with one another." We would not need metaphors if we spoke about death more directly.