"Death reigned in every corner."

The circular nature of humanity is quickly mentioned but rarely explored until moments of confounding circuity strike us in the solar plexus, and we are forced to admit: "We've been here before." In the past few post-Covid years, we've grabbed the word "plague" from history and applied it to today, and yet, is it appropriate? What is a plague?

Let's consider: "Death reigned in every corner." wrote Daniel Defoe (born in 1660 - April 24, 1731) in his 18th-century account of the black plague in Britain, Journal of the Plague Year. A part literature-part journalistic piece of writing that captures one of human history's most devasting periods of death and fear.

It is eerily familiar not simply in death but in how humans react to the fear of death.

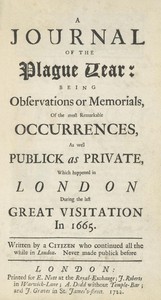

Cover page for Defoe's original publication.

Cover page for Defoe's original publication.Although the black plague hit Europe many times from 1347 to 1666, the final episode was the worst. Over a quarter of London's population died in less than two years.

Defoe's poetic language, "Death reigned in every corner," tells us much: death - not the monarch - reigned; those infected died shut up their homes, only corners to hold them; and the word death rather than illness, sickness or even plague - reminds us what was at stake.

In September 1664, news began circulating in England that the plague had returned to Holland. Information was scarce and unreliable in those days. Defoe wrote the dramatics of the event:r

It was about the beginning of September 1664, that I, among the rest of my neighbours, heard in ordinary discourse that the plague was returned again in Holland, for it had been very violent there. ... We had no such thing as printed newspapers in those days to spread rumours and reports of things, and to improve them by the invention of men ... but such things as these were gathered from the letters of merchants and others who corresponded abroad, and from them was handed the word of mouth only so that things do not spread instantly over the whole nation, as they do now. But it seems that the Government had a true account of it, and several councils were held about ways to prevent its coming over; but it was all kept very private.

Society's suspicion and fear multiplied as the scourge reached Britain and the number of dead began to toll. The parish councils' weekly Bill of Mortality showed the grave situation.

The whole bill also was very low, for the week before the bill was but 347, and the week above mentioned was 343. We continued in these hopes for a few days, but it was but for a few, for the people were no more to be deceived thus; they searched the houses and found that the plague was spread every way and that many died of it every day...the infection had spread beyond all hopes of abatement

With the plague spreading "beyond all hope of abatement", those with the most money and means relocated to the countryside where it was considered safer.

Defoe notes:

The richer sort of people, especially the nobility and gentry from the west part of the city, thronged out of town with their families and servants in an unusual manner. [...] Coaches filled with people of the better sort, and horseman attending them, and all hurrying away; the empty waggons and carts appeared, and spare horses with servants, who, it was apparent, were returning or sent from the countries to fetch more people; besides innumerable numbers of men on horseback, some alone, others with servants and, generally speaking, all loaded with baggage and fitted for travelling...

This was a very terrible and melancholy thing to see, as it was a sight which I could not but look on from morning to night, it filled me with very serious thoughts of the misery that was coming upon the city and the unhappy condition of those that would be left in it.

The "misery that was coming" was real, and after a few more weeks, Defoe noted: "the presence of London was greatly altered."

"Charles II Rules and Orders for Prevention for the Spreading of Infection of the Plague." Learn more.

"Charles II Rules and Orders for Prevention for the Spreading of Infection of the Plague." Learn more.Government officials who remained to execute affairs enforced a lockdown and marked houses with a red cross to denote infection. Wardens and nurses tended to the sick, ensuring infected individuals did not leave home. (It was not until two centuries later that the government employed "Public Disinfectors.")

That if any House be Infected, the sick person or persons be forthwith removed to the said pest-house, sheds, or huts, for the preservation of the rest of the Family: And that such house (though none be dead therein) be shut up for fourty days, and have a Red Cross, and Lord have mercy upon us, in Capital Letters affixed on the door, and Warders appointed, as well to find them necessaries, as to keep them from conversing with the sound.

From "Charles II Rules and Orders for prevention for the Spreading of Infection of the Plague"

Engraving of Daniel Defoe.

Engraving of Daniel Defoe. Defoe began his professional life as a merchant and trader and wrote novels late in life as a by-product of journalism and religious dissension. However, A Journal of the Plague Year is not about science, morality, or institutions. It is about people, in aggregate and sometimes specific. Defoe appointed himself the guardian of the human story.

One mischief always introduces another. These terrors and apprehensions of the people led them into a thousand weak, foolish and wicked things, which they wanted not a sort of people wicked to encourage them to: and this was running about to fortune-tellers, cunning-men, and astrologers to know their fortune, as it is vulgarly expressed, to have their fortunes told them, their nativities calculated, and the like; and this folly presently made the town swarm with a wicked generation of pretenders to magic, to the black art.

Defoe was as much one of the first social journalists as he was a novelist. I keep saying "novelist", and you probably wonder if this is a Journal of the Plague Year; surely literature plays no part?

Ah well, Defoe was born in 1660, which means he was five in 1665. Defoe wrote and published Journal in 1722.

Nowhere is this intimacy more present than in John Steinbeck's writing journals which actually function as a diary and were published without edited content.(Why it is not just called "Diary" owes to the rather gendered idea that a diary is something kept by day-dreaming young women, not professional men.)

On the other hand, we have George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London which Orwell edited into story before it was published.

Regardless, we owe so much to Defoe being born in 1660 (and surviving the plague). Had he written from the field, as we now say, I wonder if he would have had such distanced compassion.

John Dunstall's 1666 broadsheet etching depicts nine scenes of the plague.

John Dunstall's 1666 broadsheet etching depicts nine scenes of the plague. As dead bodies piled up, dead carts were used to pick up the deceased. Bodies tumbled into mass graves like cataracts.

I was indeed shocked with this sight; it almost overwhelmed me, and I went away with my heart most afflicted, and full of the afflicting thoughts such as I cannot describe. Just as my going out of the church, and turning up the street towards my own house, I saw another cart with links, and a bellman going before coming out of Harrow Alley .. very full of dead bodies, it went directly over the street also toward the church, it stood a while, but I had no stomach to go back again and see the same dismal scene over again.

Dafoe ends the Journal with a week of a significant drop in the weekly Bill of Mortality death numbers. It is a cautiously joyous moment.

But we move on. Perhaps to Wilfred Owen's poetic admonitions to feel something about death; Susan Sontag's study of the limits of empathy for others, my studies of the social isolation and annihilation of hunger; and - rather powerfully - the Jan Enkelmann's photographic account of London during the 2020 Lockdown which show a city abandoned, shut-down, and beautiful.