“A child's world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood."

Rachel Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964), one of the most essential environmentalists of the 20th century, spent her life reminding us we are part of—not apart from—the natural world, in all its minutiae and marvels.

From Carson's The Sense of Wonder:

[I have] always loved the lichens because they have a quality of fairyland - silver rings on a stone, odd little forms like bones or horns or the shell of a sea creature... the woods path was carpeted with the so-called reindeer moss, in reality a lichen. Like an old-fashioned hall runner, it made a narrow strip of silvery gray through the green of the woods, here and there spreading out to cover a larger area.

Lichen on stone. Lichens cover as much as eight percent of the world's surface. They are both an alga and a fungus working together to survive. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.

Lichen on stone. Lichens cover as much as eight percent of the world's surface. They are both an alga and a fungus working together to survive. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.The Sense of Wonder is Carson's most personal project. In her intimate space, like the coastline of Maine in eastern United States, Carson takes our hand and teaches us how to see things that have become invisible from abundance. Or, said alternatively she reminds us how we saw when we were young.

There is a world of little things, seen all too seldom. Many children, perhaps because they themselves are small and closer to the ground than we, notice and delight in the small and inconspicuous.

With her environmental summons to care, Silent Spring, Carson reinforced our connection to nature by demonstrating the harm of pesticides and insecticides. The Sense of Wonder is something more intimate, more personal. Carson invites us along as she ventures out with her young nephew Roger, finding harmony in the night silence.

Our adventure on this particular night had to do with life. We were searching for ghost crabs, those sand-colored, fleet-legged beings which Roger had sometimes glimpsed briefly on the beaches in daytime. But the crabs are chiefly nocturnal, and when not roaming the night beaches they dig up little pits near the surf line where they hide.

“I awoke in the center of night. ‘In movement is blessing’ […] I felt about for my journal and laid there holding it, waiting for the moon to reappear.” - Patti Smith, Woolgathering. Illustration by Jackie Morris for The Lost Spells.

“I awoke in the center of night. ‘In movement is blessing’ […] I felt about for my journal and laid there holding it, waiting for the moon to reappear.” - Patti Smith, Woolgathering. Illustration by Jackie Morris for The Lost Spells.Senses other than sight," Carson reminds us, "can prove avenues of delight and discovery." The smell of leaf mold in autumn, the sound of snow, the words we speak to name flowers. Carson believed a full-sensory perception enabled a more robust emotional response.

Seat yourself comfortable and focus your glass on the moon. You must learn patience, for unless you are on a well-travelled high-way of migration you may have to wait many minutes before you are rewarded. In the waiting periods you can study the topography of the moon, for even a glass of moderate power reveals enough detail to fascinate a space-conscious child. But sooner or later you should begin to see the birds, lonely travellers in space glimpsed as they pass from darkness into darkness.

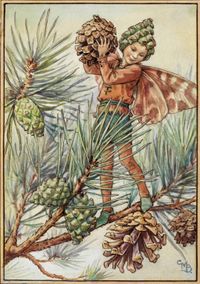

"The Pine Tree Fairy" by Cecily Mary Barker in her 1923 poetry collection Flower Fairies of Winter.

"The Pine Tree Fairy" by Cecily Mary Barker in her 1923 poetry collection Flower Fairies of Winter.Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote he felt joy to the point of sadness while gazing at the sky, and poet Pablo Neruda wrote of an instant uplift while smelling violets. Charles Darwin, meanwhile, owed it to a divine unknown the power he felt when standing among flora and fauna.

Our senses are indeed conduits through which a universal pulse echoes. Carson coaches us to a state where that pulse is most clearly felt.

You can listen to the wind, whether it blows with majestic voice through a forest or sings a many-voiced chorus around the eaves of your house or the corners of your building, and in the listening, you can gain magical release for your thoughts.

"Science isn't the only way to arrive at knowledge," wrote physicist Alan Lightman, who, like Carson, contemplated our magical existence while staring up at the Maine sky. Our intelligence percolates from emotions, sensory intake, or through opening our spiritual palm to the world.

As Annie Dillard remarked in her pilgrimage of wonder, “Beauty and grace are performed whether we see them or not; the least we can do is be there.”

Fibonacci sequence in begonia leaves.

Fibonacci sequence in begonia leaves. What is the value of preserving and strengthening this sense of awe and wonder, this recognition of something beyond the boundaries of human existence? Is the exploration of the natural world just a pleasant way to pass the golden hours of childhood or is there something deeper?

I am sure there is something much deeper, something lasting and significant. Those who dwell, as scientists or laymen, among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life.

The Sense of Wonder was Carson's most treasured project, but she never saw it published, inundated as she was by the response to the 1964 publication of Silent Spring. We are so lucky that she wrote it; our children more so. Hold it dear, think of her, and wonder what isn't known but is deeply felt.