"This book is about our desire to talk, to understand and be understood."

Psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz's generous and insightful memoir The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves is a primary inspiration for my eponymous site. Not only for name—which I humbly copied—but for purpose: to bring narrative, personhood, and meaning to the wonderfully human process of striving and settling, hating and loving, struggling and finding peace.

At one time or another, most of us have felt trapped by things we find ourselves thinking of doing, caught by our impulses or foolish choices; ensnared in some unhappiness or fear; imprisoned by our own history. We feel unable to go forward, yet we believe there must be a way. 'I want to change, but not if it means changing,' a patient once said to me in complete innocence. Because my work is about helping people change, this book is about change.

"All his attempts for love are bound to fail unless he tries to actively develop his total personality,” wrote psychoanalyst Erich Fromm in his rich study of love.

"All his attempts for love are bound to fail unless he tries to actively develop his total personality,” wrote psychoanalyst Erich Fromm in his rich study of love. Grosz believes, as do I, that self-knowledge leads us through difficult roads, silent forests, and avenues without end and that we must face wayward darkness to reconcile pain with peace.

I gather human commonalities—feelings towards our kin, the path to self-knowledge, things that bring us comfort, or things that bring us inspiration. From our thoughts on mortality and loss to the ways we love.

I add a smattering of posts about nature because I believe nature eases the path to everything good and grand.

Grosz has been a practicing psychoanalyst for almost three decades. He is based in London. The Examined Life collects and connects some of his most memorable cases.

"How we can be possessed by a story that cannot be told" is a story of a patient who acted out—even going so far as to fake his death—from an inability to articulate his pain and fear. Grosz concludes:

Experience has taught me that our childhoods leave in us stories like this—stories we never found a way to voice, because no one helped us find the words. When we cannot find a way of telling our story, our story tells us—we dream these stories, we develop symptoms, or we find ourselves acting in ways we don't understand.

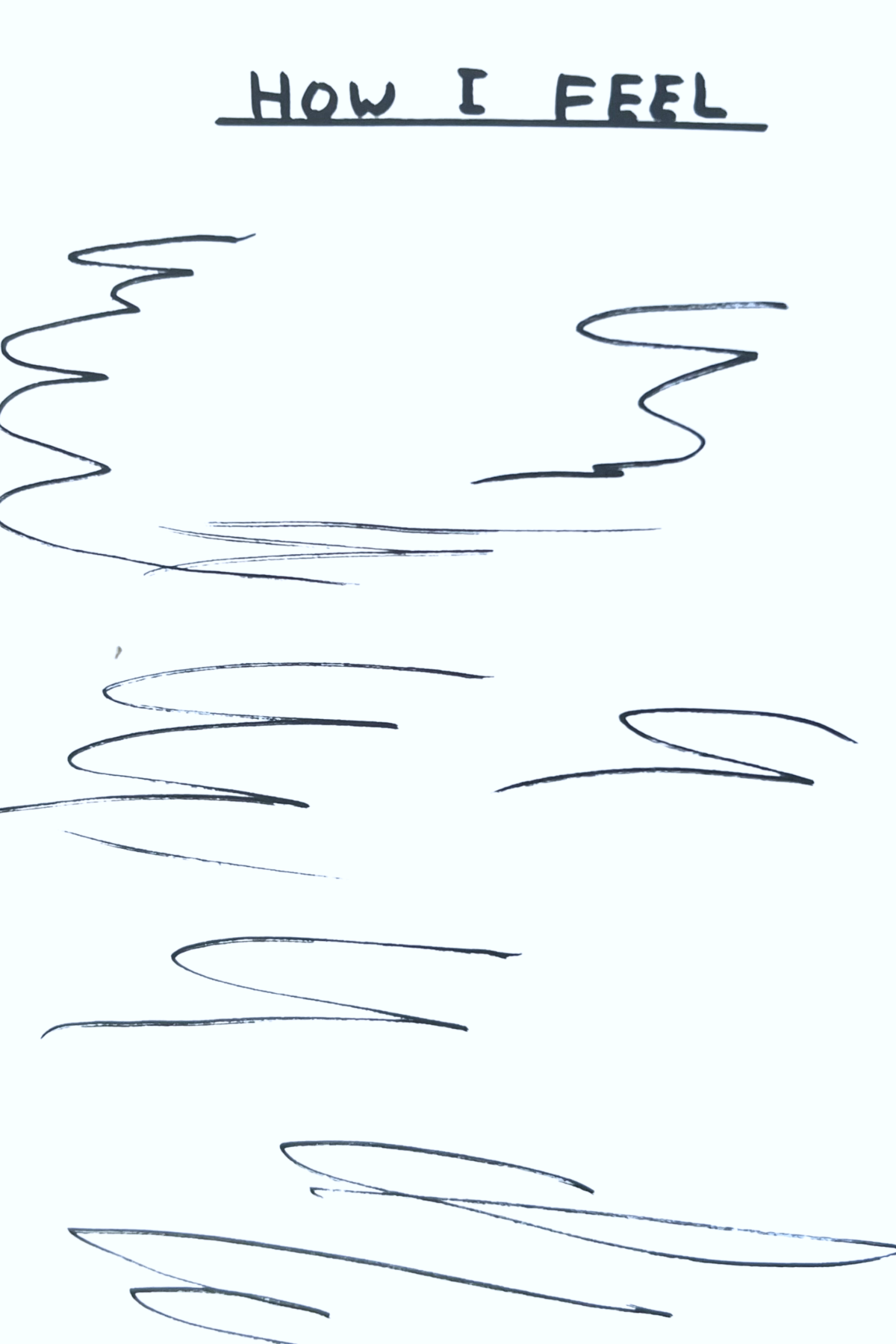

"How I Feel" by David Shrigley from his messy, perfectly absurd, utterly accurate portrait of unhappy humankind. How Are You Feeling?

"How I Feel" by David Shrigley from his messy, perfectly absurd, utterly accurate portrait of unhappy humankind. How Are You Feeling?In a story of a compulsive liar who lied profusely to keep himself safe, Grosz again helps us see beyond the behavior to the motivation:

"I used to wet my bed as a child, Philip told me. He described crumpling up his damp pyjamas and pushing them deep into the covers, only to find them at bedtime under the pillow, washed and neatly folded. He never discussed this with his mother and, to the best of his knowledge, she never told anyone, including his father, about his bedwetting. 'He'd have been furious with me,' Philip said. 'I guess she thought I'd outgrow it. And I did, when she died.'

Philip's lying was not an attack upon intimacy—though it sometimes had that effect. It was his way of keeping the closeness he had known, his way of holding on to his mother.

When a father cuts off his daughter for marrying outside her faith, Grosz works with his patient to understand that her father's guilt at an extra-marital affair likely drove his torrential judgment.

Psychoanalysts call this 'splitting'—an unconscious strategy that aims to keep us ignorant of feelings in ourselves that we're unable to tolerate. Typically, we want to see ourselves as good and put those aspects of ourselves that we find shameful in another person or group. Splitting is one way of getting rid of self-knowledge.This concept of splitting is common with those closest and most connected to us. Read more in my look at how we often fail to see our mothers distinct from ourselves.

Interestingly enough, the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges was afraid of mirrors his entire life, I wonder if it was something about the reflection, this concept of a "double" that unnerved him. In Do Mirrors Tell Us Who We Are I look at how reflections (both literal and psychological) complete or challenge our self-images.

In "How lovesickness keeps us from love," Grosz works with a patient to understand how being intensely sentimental can keep us from feeling genuine emotions.

Many psychoanalysts think that lovesickness is a form of regression, that in longing for intense closeness, we are like infants craving our mother's embrace. This is why we are most at risk when we are struggling with loss or despair or when we are lonely or isolated—it is not uncommon to fall in love during the first term of university, for example. But are these feelings really love?

Among many stories that feel achingly familiar, my particular favorite is a tender story on how the fear of loss can make us lose everything.

We are vehemently faithful to our own view of the world, our story. We want to know what new story we're stepping into before we exit the old one. We don't want an exit if we don't know exactly where it is going to take us, even—or perhaps especially—in an emergency. This is so, I hasten to add, whether we are patients or psychoanalysts.

Alive and thriving.

Alive and thriving.I want to type up the entirety of Grosz's The Examined Life and share it with you. It is one of the most comforting, inspirational, and enlightening books ever.

And yet, The Examined Life is a difficult book.

Each time I read it, I wish for a Stephen Grosz in my life—that person who would see and understand me. Write my story. I read somewhere that is why we marry, to engage a witness to our lives.

Stephen Grosz.

Stephen Grosz. We all long to be seen and loved for who we truly are. That is what Stephen Grosz's The Examined Life is about. It is what my site is about.

Find someone who can understand you, seek them out, and hold on. Or, even better, be that person to others. Can humans aspire to anything greater?