"If the word integration means anything, this is what it means: that we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it."

Less than a decade after the publication of Notes of a Native Son - a rich, vital collaboration between the mind of James Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) and the editing skills of Baldwin's childhood friend, Sol Stein - Baldwin once again shook America by its lapels to awake to its racial nightmare.

One of the earliest known photos of James Baldwin. Taken by his friend and editor Sol Stein in 1945.

One of the earliest known photos of James Baldwin. Taken by his friend and editor Sol Stein in 1945. Baldwin's The Fire Next Time (from the Biblical verse: "God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!") contains two epistles, one to his nephew and one to the world. Baldwin imagines a caring, knowledgeable recipient, Black and white alike, at whose feet this task of first racial consciousness and then salvation.

And here we are at the centre of the arc, trapped in the gaudiest, most valuable and most improbable water wheel the world has ever seen. We must assume everything is in our own hands; we have no right to assume otherwise. If we - and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfilment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign. Not more water, the first next time!

Despite their howl of urgency and anger, Baldwin's efforts to embrace pain and enable sight are resoundingly rooted in brotherly love.

A seasoned speaker, Baldwin's writing resembles a sermon to an imagined congregation. In this case, the "handful of us" are set against one another. There is so much beautiful power in his energy. It feels warm when Baldwin reminds us we are lovers and bound together.

From my favorite lines of Notes of a Native Son:

It must be remembered that the oppressed and the oppressor are bound together within the same society; they accept the same criteria, they share the same beliefs, and they both alike depend on the same reality. Within this cage it is romantic, more, meaningless, to speak of a “new” society as the desire of the oppressed, for that shivering dependence on the props of reality which he shares with the Herrenvolk makes a truly “new” society impossible to conceive.

From James Baldwin's Notes of a Native Son.

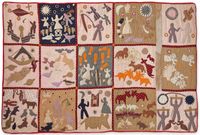

"Biblical Quilt" by Harriet Powers in 1885. Although she was born into slavery, Powers eventually became a landowner after emancipation. She sewed many bold, metaphorical, and technically brilliant quilts. Learn more.

"Biblical Quilt" by Harriet Powers in 1885. Although she was born into slavery, Powers eventually became a landowner after emancipation. She sewed many bold, metaphorical, and technically brilliant quilts. Learn more.We are together unmaking what we have wrought, and our consciousness prohibits deferral of action.

That does not mean, however, that we are equally knowledgeable. Baldwin points this out in the letter to his nephew:

Now, my dear namesake, these innocent and well-meaning people, your countrymen, have caused you to be born under conditions not very far removed from those described for us by Charles Dickens in the London of more than a hundred years ago. (I hear the chorus of innocents screaming. 'No! This is not true! How bitter you are!' - but I am writing this letter to you to try to tell you how to handle them, for most of them do not yet know that you exist. I know the conditions under which you were born, for I was there. Your countrymen were not there, and haven't made it yet.)

These lines remind me of something Billie Holiday wrote in her astounding memoirs about white folks who both loved her singing and yet looked at her like she had dropped in from another planet.

James Baldwin. "The years/ And cold defeat live deep in/ Lines along my face/ They dull my eyes, yet/ I keep on dying,/ Because I love to live." Maya Angelou's poem "The Lesson."

James Baldwin. "The years/ And cold defeat live deep in/ Lines along my face/ They dull my eyes, yet/ I keep on dying,/ Because I love to live." Maya Angelou's poem "The Lesson."As German psychoanalyst Erich Fromm noted, we never truly know one another. But we can, as Elie Wiesel advised in his memoirs of the Holocaust, understand one another. Or aim to.

Baldwin's goal is the same.

Lines like "you must accept them..." will coil around your gut when you realize Baldwin is telling his people, born into the place of Dickens, to overcome their oppression with love. And that you, my fellow white reader, are the recipient of such devotion.

The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them. And I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love. For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released. They have had to believe for many years, and for innumerable reason, that black men are inferior to white men. Many of them know better, but as you will discover, people find it very difficult to act on what they know. To act is to be committed, and to be committed is to be in danger. In this case, the danger of most white Americans is the loss of their identity. Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shining and all the stars aflame. You would be frightened because it is out of the order of nature. Any upheaval in the universe is terrifying because it so profoundly attacks one's sense of one's own reality.

But these men are your brothers - your lost, young brothers. And if the word integration means anything, this is what it means: that we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it.

To read James Baldwin as a white American is to be shaken into the highest possible consciousness and the highest possible guilt. But that guilt is soon pressed into responsiveness by gratitude. Gratitude that Baldwin never once calls us ignorants, but rather innocents. And calls on us to be loved.

Harriet Powers' pictorial quilt, 1895, featuring Biblical scenes like the Baptism of Jesus, and Adam and Eve in the Garden, as well as non-religious images like the Leonid Meteor Storm that happened over North America in 1833. Learn more.

Harriet Powers' pictorial quilt, 1895, featuring Biblical scenes like the Baptism of Jesus, and Adam and Eve in the Garden, as well as non-religious images like the Leonid Meteor Storm that happened over North America in 1833. Learn more.Baldwin's line "Your countrymen were not there..." isolates the mindset of this young adolescent from white society while Baldwin's coda "I was there" builds in unity with his Black kin. We might be bound together but are not the same in knowledge.

Baldwin teaches, lectures, cajoles, and sometimes hits us with unfathomable truths, but he also loves his fellow men profoundly and purely.

Walk away from this book in deep, resounding love. Love and commitment to do better.

Awaken your soul a bit more with Pema Chödrön's lessons on rebuilding spirits and our connections, Simone Weil's treatise on the elevating nature of grace, Maya Angelou's love letter to women everywhere, and my study of feelings beyond language.