"To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul."

In 1933 English journalist and author George Orwell published the diary he kept while living (by choice) among the poor in Paris and London. Orwell said living among the poor formed his literary need to address injustice.

While Orwell revolutionized his thinking, he ultimately returned to his status as a person without perpetual hunger. Orwell was unable to feel - and thus observe - the rootlessness inherent in poverty.

American Jazz singer Billie Holiday clarifies it perfectly in her memoirs;

"In the early thirties when Mom and I started trying to kick and scratch out a living in Harlem, the world we lived in was still one that white people made. But it had become a world they damn near never saw. These places weren't for real. the life we lived was. But it was all backstage, and damn few white folks ever got to see it. When they did, they might as well have dropped in from another planet. Everything about it seemed to be news to them."

And in another section Holiday comments that the brothel in which she cleaned was the only place white and black people met socially.

One of five wire sculptures by Portugues tri-dimensional artist David Oliveria which toured the UK as part of the #NowYouSeeMe campaign to end youth homelessness. Learn more.

One of five wire sculptures by Portugues tri-dimensional artist David Oliveria which toured the UK as part of the #NowYouSeeMe campaign to end youth homelessness. Learn more.By rootlessness, I mean a feeling of deep insecurity in the moral, intellectual, and spiritual space protected and administered by a nation-state. A rootlessness that reaches the very sinews and cells of the embodied soul.

For example, while Orwell witnessed individuals committing crimes, he did not see law-breaking as a means of resistance to alienation from that same law.

George Orwell's poem was written when he was eleven and published under his real name, Eric Blair. The poem was published on Oct 2, 1914, as a rallying cry for patriotism. © Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard.

George Orwell's poem was written when he was eleven and published under his real name, Eric Blair. The poem was published on Oct 2, 1914, as a rallying cry for patriotism. © Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard.About a decade after Orwell's romp, philosopher Simone Weil (April 3, 1909 - August 24, 1943) was asked by French patriots how France, as a nation embattled by occupation and psychological diminution, could move forward (triumphantly, one assumes). Weil tackled the issue of nationalism with a deeply felt argument that to feel connected to one's country, one must feel like he belongs in that country. She finished the paper in 1942, and it was published in 1949 as The Need for Roots.

To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul. It is one of the hardest to define. A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active, and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future. This participation is a natural one, in the sense that it is automatically brought about by place, conditions of birth, profession, and social surroundings. Every human being needs to have multiple roots. It is necessary for him to draw well-nigh the whole of his moral, intellectual, and spiritual life by way of the environment of which he forms a natural part.

Weil acknowledged that while we find ourselves organized by a nation-state apparatus, this structure is limited:

We find in the history of all countries the most surprising ups and downs, sometimes following quite swiftly upon one another. But if the country is subdued by foreign arms, there is nothing left to hope for, save the possibility of a rapid liberation. Hope alone, is worth dying to preserve when nothing else is left.

Thus, although one's country is a fact, and, as such, subject to external conditions, to hazards of every kind, in times of mortal danger there is nonetheless an unconditional obligation to go to its assistance. But it is obvious that the people will show all the greater ardour in its defence the more they will have been made to feel its reality.

National grandeur - a sentiment of patriotism or looking upon one's country as a means of self-bolstering - is equally feckless.

'We cannot let men die,' he seemed to say, "Without inheriting a deeply fractured self.'

This defiance was unique in a time when great British writers, Kipling and Wells to name a few, were called upon by the British government to write pro-War pamphlets.

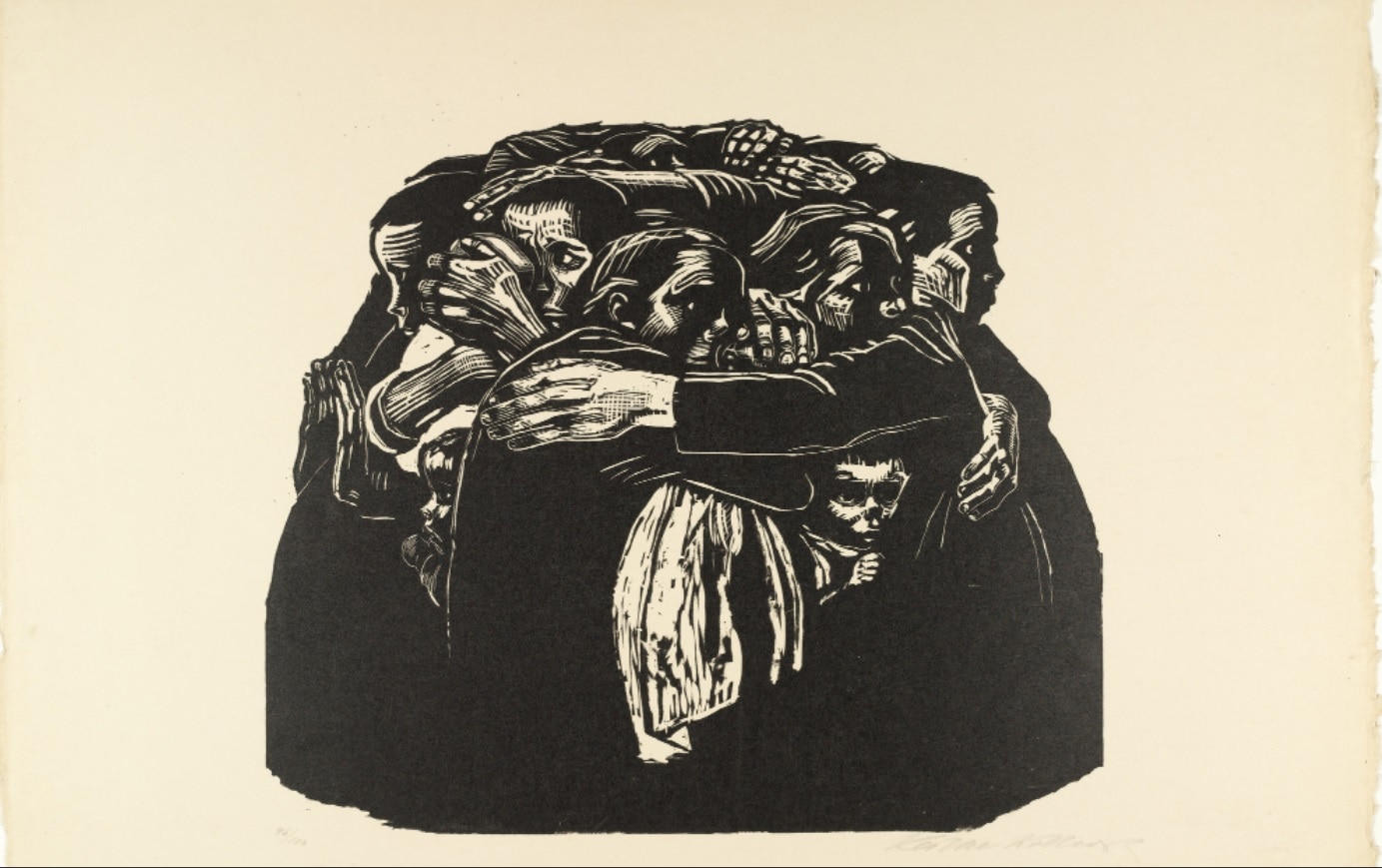

"The Mothers (Die Mutter) from War (Krieg) from 1921-22 woodcut, published in 1923. Käthe Kollwitz's War series focused on the vulnerable members of society, like widows, children, and even the working class, affected by social traumas like WWI. Learn more.

"The Mothers (Die Mutter) from War (Krieg) from 1921-22 woodcut, published in 1923. Käthe Kollwitz's War series focused on the vulnerable members of society, like widows, children, and even the working class, affected by social traumas like WWI. Learn more. Compassion- not pride- is needed to rebuild any nation and grow roots.

Yet, there is one, no less vital, absolutely pure, and corresponding exactly to present circumstances. It is compassion for our country. We have a glorious respondent. It was Joan of Arc who used to say she felt pity for the kingdom of France.

[...]

This poignantly tender feeling for some beautiful, precious, fragile, and perishable object has a warmth about it which the sentiment of national grandeur altogether lacks. The vital current which inspires it is a perfectly pure one and is charged with an extraordinary intensity. Isn't a man easily capable of acts of heroism to protect his children, or his aged parents?

If compassion is the metal of rootedness, how is that achieved? How do you make people care? Weil suggested moral, social, and political orientation towards a higher code of obligations.

The notion of obligations comes before that of rights, which is subordinate and relative to the former. A right is not effectual by itself, but only in relation to the obligation to which it corresponds, the effective exercise of a right springing not from the individual who possesses it, but from other men who consider themselves as being under a certain obligation towards him. Recognition of an obligation makes it effectual. An obligation that goes unrecognized by anybody loses none of the full force of its existence. A right that goes unrecognized by anybody is not worth very much.

[...]

Rights are always found to be related to certain conditions. Obligations alone remain independent of conditions. They belong to a realm situated above all conditions because it is situated above this world... The realm of what is eternal, universal, and unconditional is other than the one conditioned by facts, and different ideas hold sway there, ones which are related to the most secret recesses of the human soul.

Although Weil was deeply spiritual, a converted Catholic, her notion of realms is universally applied. Mary Oliver called it "the eternal"; Emerson referred to it as "Something," and in my opinion, W. B. Yeats referred to it as a "contemplation of what is difficult." It is a belief that something is outside the mortal scope (a being, a body, a language, a law...) and that something is more significant, grander, purer, and brighter than anything else.

To this something, Weil was convinced, we are obligated. But she admits that it could only grow roots when expressed through "the medium of Man's earthly needs."

On this point, the human conscious has never varied. Thousands of years ago, the Egyptians believed that no soul could justify itself after death unless it could say: I never let any one suffer from hunger.' All Christians know they are liable to hear Christ himself say to them one day: I was hungered, and ye gave me meat.'... To no matter whom the question may be put in general terms, nobody thinks that any man is innocent, if, possessing food himself in abundance and finding some one on his doorstep three parts dead from hunger, he brushes past without giving him anything.

So it is an eternal obligation towards the human being not to let him suffer from hunger when one has the chance of coming to his assistance.

Weil enumerates additional eternal obligations: protection against violence, housing, clothing, heating, hygiene, and medical attention in case of illness. And additionally, items related to the moral rather than the physical side of Man's needs.

Simone Weil

Simone WeilI mentioned, figuratively, that Orwell left poverty and went home and had supper. Weil did not. A year after she completed The Need for Roots, Weil died from malnutrition because she had confined herself to the rations of French citizens during the Nazi occupation.

It is easy (even appealing) to categorize Weil in today's - or even her own day's - political terms. However, Weil represented the complexity of mortal life put in alignment by the grace of eternal life. She advocates for private property and property access, for a state to administer our rights and the worker's foremost needs. She contradicts herself and has youthful folly.

Notwithstanding her complexity, the value of her work to our intellectual, spiritual, and undoubtedly moral soul and social body is undeniable.

The only kind of introduction that could merit permanent association with a book by Simone Weil would be... an introduction by someone who knew her. The reader of her work finds himself confronted by a difficult, violent, and complex personality... I lack these qualifications. My aims in writing this preface are, first, to affirm my belief in the importance of the author and of this particular book, second, to warn the reader against premature judgment and summary classification - to persuade him to hold in check his own prejudices and at the same time to be patient with those of Simone Weil. Once her work is known and accepted, such a preface as this should become superfluous.

From T. S. Eliot's Preface to The Need for Roots

I take those words "Once her work is known and accepted" to heart. I had never read Weil before beginning The Examined Life. Is she taught to the youth? Is she too difficult?

As you circle the piece, the human elements become more visible, and the effect of the sculpture's weightlessness is more meaningful. Artwork by David Oliveira

As you circle the piece, the human elements become more visible, and the effect of the sculpture's weightlessness is more meaningful. Artwork by David OliveiraRebecca Solnit wrote that being lost could signify the entry to expanded consciousness. We ought to enter Weil's work with a desire - in the words of Weil's countryman and enthusiastic admirer, Albert Camus - "to inaugurate the impulse of consciousness."

Read his full speech here.

The role of a nation-state is to protect and provide for its citizens. It must also give its citizens the means to feel rooted in both geophysical space and the body politic. It is the core of nationalism, patriotism, and maintaining a healthy society. Read more in Martin Luther King Jr.'s missive on the tension needed to address social injustice, James Baldwin's first-hand account of otherness echoed in Toni Morrison's precise words on "othering" and Ocean Vuong's verse on ancestry that flows across oceans and borders.

They are all prophetic souls who live and write rootlessness with acute truth.