"We loaf through life, fritter ourselves on form and farce. Online in days of torment and desolation we sense the timeless ground of life, That one ground sometimes illumined by dark dreams."

The exquisite The Seasons of the Soul is a carefully selected anthology of Hermann Hesse's (July 2, 1877 – August 9, 1962) poetry translated into English and illuminatingly introduced by Ludwig Max Fischer, professor of German and comparative mythology. Seasons tenderly expresses this need to be seen as a sort of social awareness, even consciousness.

From Fischer's Introduction:

The soul, love, inspiration, the mysteries of nature, the unknowable divine, time, and the stages of life are the major agents in Hesse's world and are as relevant today as when he distilled them from his life experience. As an active witness in turbulent times, Hesse retained individual integrity while acting with social consciousness toward the pressing issues of society.

Few authors resonate with me as greatly as Hesse has. I found Steppenwolf in our high school library. I carried it everywhere.

It felt achingly familiar: a rupture of self, restless anger, loathing, and a need for shameful solitude. One after another, his novels spoke to me deeply in low, urgent tones of things no one else mentioned.

Jungfrau mountain range, Swiss Alps.

Jungfrau mountain range, Swiss Alps. To read Hesse's poetry—his most clear expression of being—is to feel his hope, his desire for a peaceful surrender to words, time, and indeed nature.

This ice-clear conviction of truth and knowledge is echoed in Wendell Berry's argument that "there is more to use than anyone might suppose" as it relates to the limits of knowledge. Both writers remind me of Hesse's quest to push the boundaries of knowledge of self.

Bush and meadow, field and tree,

stand in their self-sufficient silence.

Each belonging wholly to itself.

Each deep in its own dream.

Clouds float by and stars stream light

as if appointed as higher sentinels

and the mountain with its steep ridges

towers above, dark, tall, and distant.

From "Walking at Night"

Starry night, Wales.

Starry night, Wales. Rainer Maria Rilke, born three years before Hesse, urged us to seek life's answers within. Hesse similarly tilts his gaze inward and shuffles his demons.

Hermann Hesse, 1905, by Ernst Würtenberger.

Hermann Hesse, 1905, by Ernst Würtenberger.Perhaps he is so present, almost as if he whispers to us, because he projects, expands, and extends himself generously through every word. "Only I am alone with anguish and grief," the poem continues. From this inquietude comes surprisingly extroverted communion; more than expressing his own sorrows, Hesse tries to reach ours. American novelist Marilynne Robinson once wrote that loneliness creates a communion, indeed, a "truer bond among people than any kind of proximity."

Hesse's writing certainly spoke to me from solitude.

Do you know this too?

You are in the middle of a cheerful party,

When a sudden stillness takes hold of you,

And you hastily have to leave the happy hall.

Back in your bed, you lay awake

like someone suffering from a sudden heartache.

The fun and laughter disappear like smoke

And you break into tears: do you know this too?

From "Do You Know This Too?"

Hesse is masculine but vulnerable, solitary but feminine. His idea of love is to be consumed. "I wish I were a flower," he writes of love, "And [you] picked me as your own and held me captive in your hand." There is much here for the soul, the mind, and the beautiful, hidden self.

When the days turn gray

and the world looks cold and unkind,

your tentative, tender, timid trust

is then thrust back on itself.

When there is no further way forward

and your old life has lost its luster

your faith will find new paths

to new heavens never dreamt of.

What was foreign and hostile to you,

you will find nested in your inmost center.

You give your destiny another name,

throw your arms around it.

Whatever seemed to beat you down,

now shows its friendship freely, provides inspiration,

serves as a guide, as a messenger,

to call you always toward greater heights.

From "Fateful Days"

The poetry of Marianne Moore (a contemporary of Hesse but continents apart) is a thoughtful collection to read in tandem. She projects a heroic effort to care, to pay attention, which could be a response to Hesse's outstretched need.

Man looking into the sea,

taking the view from those who have as much right to it as you have to yourself,

it is human nature to stand in the middle of a thing,

but you cannot stand in the middle of this;

the sea has nothing to give but a well-excavated grave.

The firs stand in a procession, each with an emerald turkey-foot at the top,

reserved as their contours, saying nothing;

repression, however, is not the most obvious characteristic of the sea;

the sea is a collector, quick to return a rapacious look.

There are others besides you who have worn that look—

whose expression is no longer a protest; the fish no longer investigate them

for their bones have not lasted [...]

From Marianne Moore's "A Grave"

Read the full poem here.

Companion Hesse's vital verse with 2,000-year-old essays on the interconnectedness of all things from Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius or with Emerson's Transcendental philosophy that nature unites and uplifts us.

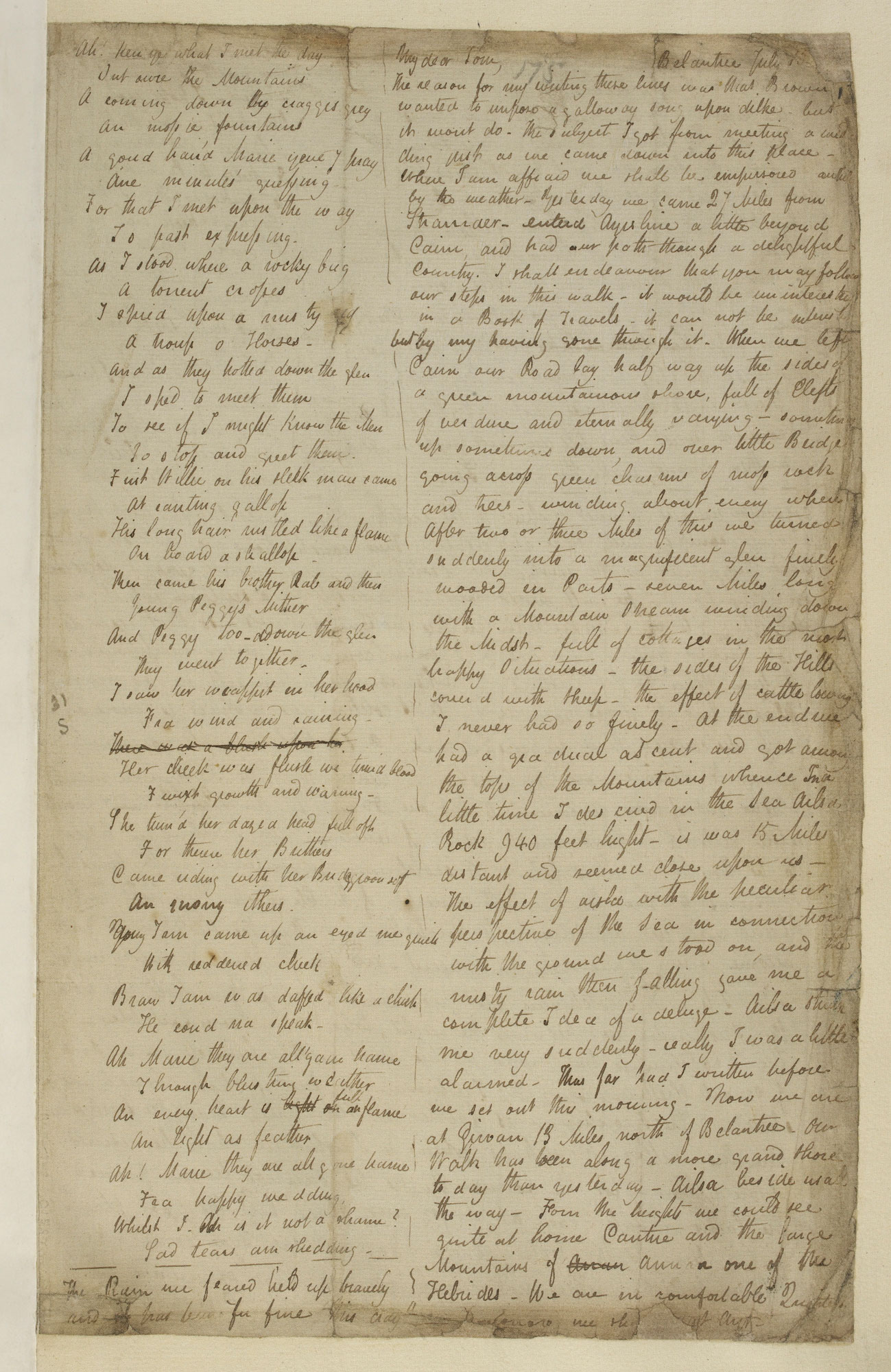

John Keats' letter to his brother Tom was written on July 10-18, 1818. Tom died from tuberculous in December of the same year; Keats had been with him but took a walking holiday in July to reacquaint himself with nature. Learn more.

John Keats' letter to his brother Tom was written on July 10-18, 1818. Tom died from tuberculous in December of the same year; Keats had been with him but took a walking holiday in July to reacquaint himself with nature. Learn more.Hesse's poetry also dances beautifully with the contemplative self-acceptance in Kakuzo Okakura's 1906 The Book of Tea. The Japanese scholar writes: "Those who cannot feel the littleness of great things in themselves are apt to overlook the greatness of little things in others."

Often, I think Hesse had no other purpose.