"Life is constantly experimenting, innovating and adapting."

What is life? What is not life? What is a meaningful life?

In his recently published What is Life? Five Great Ideas in Biology, Sir Paul Nurse (born on January 25, 1949), a Nobel Prize-winning geneticist, neatly answers a fundamental yet baffling question: what does it mean to be alive?

It begins with cells.

I saw my first cell when I was at school... My class had germinated onion seedlings and squashed their roots under a microscope slide to see what they were made from. My inspirational biology teacher, Keith Neal, explained that we would see cells, the basic unit of life.

And there they were: neat arrays of box-like cells, all stacked up in orderly columns. How impressive it seemed that the growth and division of those tiny cells were enough to push the roots of an onion down through the soil, to provide the growing plant with water, nutrients, and anchorage.

As I learned more about cells, my sense of wonder only grew. Cells come in an incredible variety of shapes and sizes...If you had an egg for breakfast, consider the fact that the whole of its yolk is just one single cell.

The cell, Nurse instructs us, is the basic unit of life, just as the atom is the basic unit of matter. Life is unexpectedly modular: everything alive on the plant is either a cell or made from a collection of cells.

"So it is that only when we bring our focus to bear, first on the individual cells of the body, then on the minute structures within the cells, and finally on the ultimate reactions of molecules within these structures—only when we do this can we comprehend the most serious and far-reaching effects of the haphazard introduction of foreign chemicals into our internal environment."

In 2001 Nurse won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for determining the molecules responsible for cell regulation and reproduction. Learn more.

In 2001 Nurse won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for determining the molecules responsible for cell regulation and reproduction. Learn more.If a cell is, among many other things, the engine of life, its most unique property is its form.

A critically important part of a cell... is its outer membrane. Although just two molecules thick, this outer membrane forms a flexible 'wall' or barrier that separates each cell from its environment, defining what is 'in' and what is 'out.'

Both philosophically and practically, this barrier is crucial. Ultimately, it explains why life forms can successfully resist the overall drive of the universe toward disorder and chaos. Within their insulating membranes, cells can establish and cultivate the order they need to operate while creating disorder in their local surroundings outside the cell.

When I contemplated What is a Wall? I considered both the psychophysical embracing more maternal aspects of a wall as well as the unforgiving, even quietly aggressive aspects. The same structure that humans have built throughout time means so many different things depending on our experience or vantage point. But I never imagined a wall would have properties of life itself or be responsible for life's boundaries.

Another philosophical player in the distinction of life is equally simple: genes. A series of traits passed on, occasionally adjusted, are responsible for every iota of life on earth. In a universe that tends towards flux ("Life is constantly experimenting, innovating and adapting," writes Nurse), the genes create continuity of being.

"Darwin amassed huge amounts of observational data from the fossil record and his studies of plants and animals, both at home and abroad. He organized it all to provide strong evidence for the view, shared by Lamarck, his grandfather and others, that living organisms do evolve. But Darwin did more than that when he proposed natural selection as a mechanism for evolution. He joined up all the dots and showed the world how evolution could actually work."

Read more of Darwin's singular role in our understanding of life in The Voyage of the Beagle.

Over aeons of time, different species have risen to prominence, their forms changing beyond recognition as they have explored new possibilities and interacted with different environments and other living creatures. All species - including our own - are in a state of perpetual change, eventually becoming extinct or developing new species.Nurse continues: "For me this story of life is just as full of wonder as any of the creationist myths. Whereas most of the religious stories present us with creative acts that are familiar, even somewhat mundane, and durations of time that we can readily understand, evolution by natural selection pushes us to imagine something much more at the edge of our comfort zone, but also more magnificent."

I will make more space for such discussions in the future, The Examined Life is politically - and therefore theologically neutral - but there is excellent humanity on both sides: from atheists such as Christopher Hitchens and Albert Camus or theists Marilynne Robinson, Francis Collins and the Dalai Lama.

Pigeon nest and eggs found outside our apartment. The yolk of an egg is a single cell. One of the membranes had broken after the nest was abandoned and I had to be extremely careful handling what had become a rotten egg.

Pigeon nest and eggs found outside our apartment. The yolk of an egg is a single cell. One of the membranes had broken after the nest was abandoned and I had to be extremely careful handling what had become a rotten egg.Our little cell, charged as the building block of life and its blueprint messenger, also leads to the expression of life. The cell is actively communicating with everything around it. Think of the cell as a highly extroverted person who speaks, connects, receives, speaks more, and connects even more and thrives in this environment.

The cell is a social hub. Nurse explains:

Information is at the centre of all life. For living organisms to work effectively as complex, organized systems, they need to constantly collect and use information about the outer world they live in and their internal states. When these worlds - either outer or inner - change, organisms need ways to detect those changes and respond. If they do not, their futures might turn out to be rather brief.

This vast communication system delivers some predictability to life's existence, propagation, and extinction. It also means that geographically, vertically up and down the food chain, and throughout eras - all life is interconnected at the cellular and genetic levels.

This interconnectedness and communicative intelligence is the focus of Wislawa Syzmborska's glorious and perfect poem "Microcosmos:"

The glass doesn't even touch them;

They double and triple unobstructed,

with room to spare, willy-nilly,

To say they're many isn't saying much.

The stronger the microscope

The more exactly, avidly they're multiplied.

They don't even have decent innards.

They don't know gender, childhood, age.

They may not even know they are - or aren't.

Still, they decide our life and death.

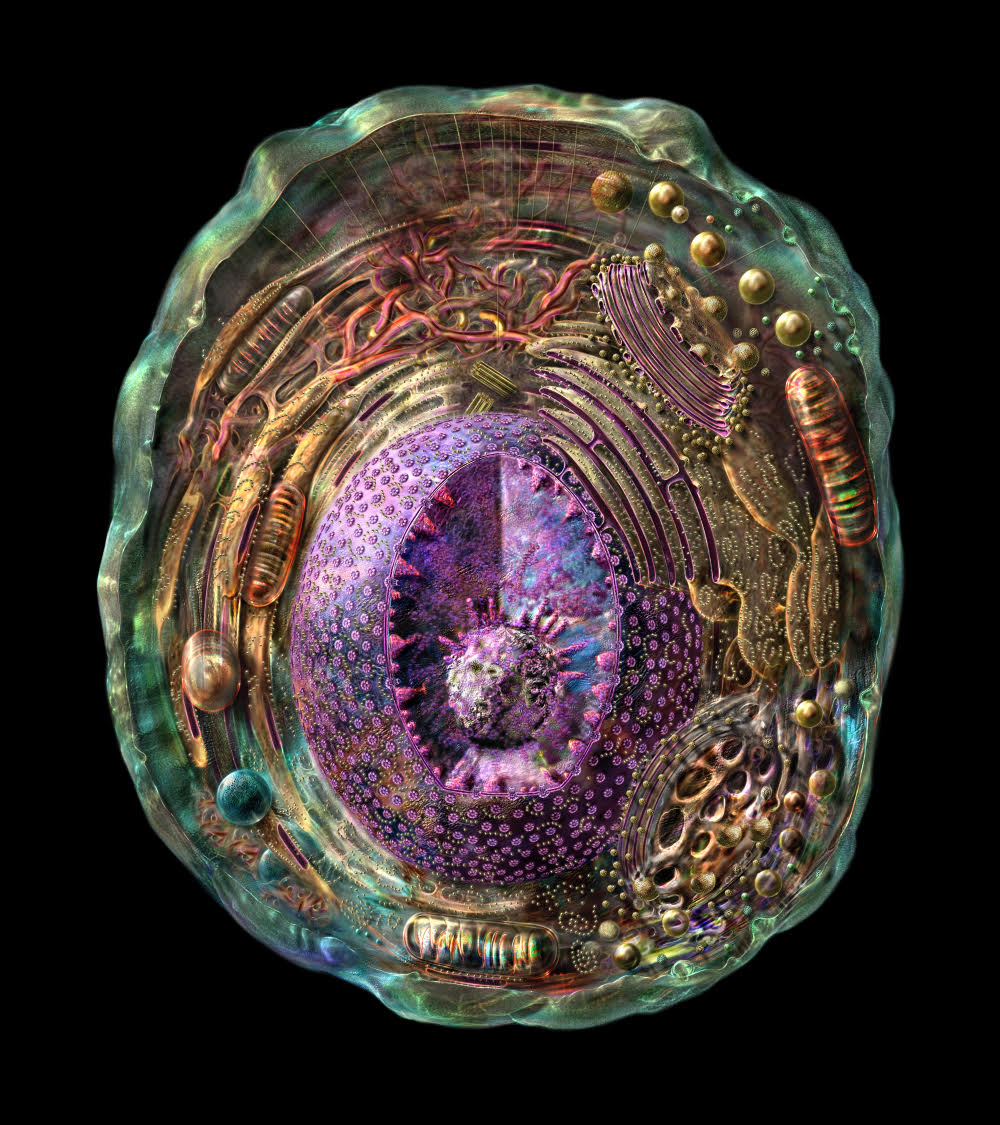

This gorgeous little cell has made the rounds on social media as the most detailed image of a cell ever taken. It's not. It's actually an exquisite and accurate digital illustration of a generic animal cell by Russell Kightley. See more of Kightley's stunning work or purchase a print here. © Russell Kightley

This gorgeous little cell has made the rounds on social media as the most detailed image of a cell ever taken. It's not. It's actually an exquisite and accurate digital illustration of a generic animal cell by Russell Kightley. See more of Kightley's stunning work or purchase a print here. © Russell KightleyThe power in these little cells moves about mountains, breaks apart forests, and constructs cities. It types these words for me. Humanist and physicist Alan Lightman surmised we are made of stardust and wondered how that stardust amounted to life. Biologist and brilliant writer Rachel Carson warned that our biological interconnectivity is the key to understanding our environment and ourselves, a theme echoed in Frans de Waal's argument for our naturally formed empathy. And let us not forget the emotionally generous Walt Whitman, whose anthem of self, "Song of Myself," assured humankind that "every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you."

So, what is life? Well, the next time you hear a report of "Evidence of life on Planet X," ask:

Are there bound cells?

Do the cells reproduce through a variable hereditary system?

Do the cells have a metabolism to survive, grow, and reproduce?

Are these systems coordinated and regulated by information flow?

Or hold this magnificence in the palm of your mind and conceive your complexity (but do not omit to thank your little cells for making that contemplation possible).