"The stars awaken a certain reverence, because though always present, they are inaccessible."

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Stars. These constant companions we frequently contemplate. They place us firmly on earth and lift us in transcendental transmogrification.

Maybe because we see them at night when we are most thoughtful. Or because we are made of the same elements, the same dust. Whatever the reason, we understand stars more than ever, yet they deliver such imagined greatness.

Biologist Rachel Carson spent her life uncovering the grim reality present in impossibly small stretches of life, yet she stood in simple rapture at stars.

Carson’s dearest work, however, and one she never saw published, was The Sense of Wonder in which she wrote of the emotional connection awakened by our observation of nature.

We lay and looked up at the sky and the millions of stars that blazed in darkness. The night was so still that we could hear the buoy on the ledges out beyond the mouth of the bay. Once or twice a word spoken by someone on the far shore was carried across on the clear air. A light burned in cottages. Otherwise, there was no reminder of human life; my companion and I were alone with the stars.

From Rachel Carson’s The Sense of Wonder

Or consider this simple, poignant observation from neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks, who looked to the stars as he was dying to anchor his existence and provide a measure of time.

A few weeks ago, in the country, far from the lights of the city, I saw the entire sky “powdered with stars” (in Milton’s words); such a sky, I imagined, could be seen only on high, dry plateaus like that of Atacama in Chile. […] It was this celestial splendor that suddenly made me realize how little time, how little life, I had left. My sense of the heavens’ beauty, of eternity, was inseparably mixed for me with a sense of transience – and death.

From Oliver Sacks’ Gratitude

Stars keep time preposterous to our own. Maybe that is why they speak eternity to us. And yet, they have materiality; they are made of elements (elements that came out of the stars and also formed us).

Elements fascinated Sacks; elements were things he collected and held dear. In his last months alive, however, he didn’t see the materiality of stars but rather their metaphor of light and life.

We now know stars to be turbulent and fraught with change. But only centuries ago – a blip in human time – we believed stars to be sentinels of heaven, part of a perfect celestial sphere occupied by gods.

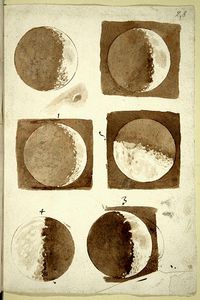

In 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus formulated a heliocentric model of the universe. But it was only a theory. It wasn’t until 1610, when Galileo Galilei, aided by his hand-fashioned telescope, conjectured that “stars” around Jupiter were not stars but moons, that astronomers began to change their view of the heavens. He also noticed mountains and valleys on our moon.

Galileo Galilei's Phases of the Moon shows earth-like scapes demonstrating the imperfection of these heavenly bodies. First published in 1610 in Sidereus Nuncius or The Starry Messenger.

Galileo Galilei's Phases of the Moon shows earth-like scapes demonstrating the imperfection of these heavenly bodies. First published in 1610 in Sidereus Nuncius or The Starry Messenger.Galileo’s findings meant Earth was not the only body around which things orbited and that our moon, situated in the perfect sky, wasn’t perfect.

The arrow of time and discovery tracks from Galileo’s brilliant use of instrumentation, which changed our conceptual notions of space, to the recent photographs of a black hole, which again changed our notions of space.

And yet, despite all of this knowledge, data, science, and understanding of what stars are, both themselves and about us, we persist in giving stars human and even divine meaning.

We return them to their perfect spheres.

In 1836, American writer and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (who would have known stars were material, not aspects of the gods) wrote:

If a man would be alone, let him look at the stars. The rays that come from those heavenly worlds will separate between him and what he touches. The stars awaken a certain reverence because though always present, they are inaccessible.

From Ralph Waldo Emerson Nature

These “inaccessible stars” formed the essence of Transcendentalism. Something that lifts us and scatters us into an expanded feeling of wisdom and knowledge of ourselves and the universe.

Standing on the ground in Massachusetts, Emerson saw the same stars as physicist and humanist Alan Lightman 150 years later. Lightman, a writer and academic forever searching for anchorage in an uncertain universe, stood on the Maine shore (just like Rachel Carson) and found infinite power in the scope of stars.

He is a wonderful seeker of certainty.

I felt an overwhelming connection to the stars as if I were part of them. And the vast expanse of time – extending from the far distant past long before I was born and then into the long distant future long after I will die – seemed compressed to a dot.

From Alan Lightman Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine

Lightman’s calm rapture triggered a contemplative journey of life, death, and, much like Sacks, meaning. The stars lit the way.

Can a ball of gas do all this? Stars do possess virtuous qualities: they are bright (light has always meant knowledge, sometimes goodness), predictable, unaffected, and relatively constant. They give us direction and security.

One of my favorite features of humanity is we allow meaning to exist apart from knowledge. Stars are a metaphor. “Metaphor is a way of thinking before it is a way of seeing,” writes James Geary in his curious and methodical study of metaphor.

Metaphor systematically disorganizes the common sense of things – jumbling together the abstract with the concrete, the physical with the psychological, the like with the unlike – and reorganizes it into uncommon combinations.

From James Geary’s I is An Other

We seek metaphor – and use metaphor – more than we realize, and have done so for thousands of years. We know what stars are and yet they both remain “inaccessible”. We cannot truly know a star – cannot see it close, touch it, taste it, or feel it – thus, we turn it into a metaphor.

My siblings and I have a star named after us. A gift from an imaginative relative. We have a certificate, our three names, and the ampersands between them. One-third of a massive ball of gas is named after me. Delightful.

And yet… Will I consider it when I am dying?

“I would like to see such a sky again when I’m dying,” wrote Oliver Sacks. I wonder if he did. No doubt he imagined them in his mind.

No doubt he imagined them to be greater than he ever knew them to be.