"The bread, the soup - those were my entire life. I was nothing but a body. Perhaps even less: a famished stomach. The stomach alone was measuring time."

Hunger reduces a soul to a body and a body to an immobile necessity-seeking thing. It is one of the most ruinous desires we can have as humans.

Or is it?

Surely appetite, or longing as hunger, is a motivator of human invention and adaptation. “One of the major pleasures in life is appetite,” wrote Laurie Lee, a literary master of memory and longing, “It is one of our major duties to preserve it.”

Appetite is the keenness of living; it is one of the senses that tells you that you are still curious to exist, that you still have an edge on your longings and want to bite into the world and taste its multitudinous flavours and juices. By appetite, of course, I don’t mean just the lust for food, but any condition of unsatisfied desire, any burning in the blood that proves you want more than you’ve got, and that you haven’t yet used up your life.From Laurie Lee’s I Can’t Stay Long

Even poet Mary Oliver argued, "I am devoted to Nature too, and to consider Nature without this appetite – this other-creature-consuming appetite – is to look with shut eyes upon the miraculous interchange that makes things work, that causes one thing to nurture another.”

Oliver’s and Lee’s take on appetite as a means of motivation and “keeping one’s expectations alive” is echoed in Ernest Hemingway’s journals of being a young writer in Paris. Although Hemingway called it “hunger.”

You got very hungry when you did not eat enough in Paris because all the bakery shops had such good things in the windows, and people ate outside at tables on the sidewalk so that you could see and smell the food. When you had given up journalism and were writing nothing that anyone in America would buy, explaining at home that you were lunching out with someone, the best place to go was Luxembourg from the Place de L’Observatoire to the rue de Vaugirard. There you could always go into the Luxembourg museum, and all the paintings were sharpened and clearer and more beautiful if you were bell-empty, hollow-hungry. I learned to understand Cézanne much better and see truly how he made landscapes when I was hungry. I used to wonder if he were hungry too when he painted; but I thought possibly it was only that he had forgotten to eat. It was one of those unsound but illuminating thoughts you have when you have been sleepless or hungry. Later I thought Cezanne was probably hungry in a different way.

From Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast

For both writers, appetite/hunger is a generator of human striving and learning, most efficient when the desired object is in plain view (but denied). What is extraordinary, then, is that while appetite and object-based hunger might enlighten and expand our knowledge, extreme hunger does the exact opposite.

In the late 1920s, George Orwell slipped off the comfort of society and lived “down and out” in Paris and London. With a desire to live amongst the poor and write what he saw, Orwell provides an authentic experience without sacrificing the observant mind of a journalist/writer.

You discover what it is like to be hungry. With bread and margarine in your belly, you go out and look into the shop windows. Everywhere there is food insulting you in huge, wasteful piles; whole dead pigs, baskets of hot loaves, great yellow blocks of butter, strings of sausages, mountains of potatoes, vast Gruyere cheese like grindstones. A snivelling self-pity comes over you at the sight of so much food. You plan to grab a loaf and run, swallowing it before they catch you; and you refrain, from pure funk.

From George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London

Orwell’s lines are reminiscent of Hemingway’s but lack a positive uplift. Perhaps because while Hemingway returned nightly to an apartment, a warming stove, and the abundant aegis of friends like Gertrude Stein, Orwell lived the life of a genuinely impoverished: homeless, anonymous, and hopeless.

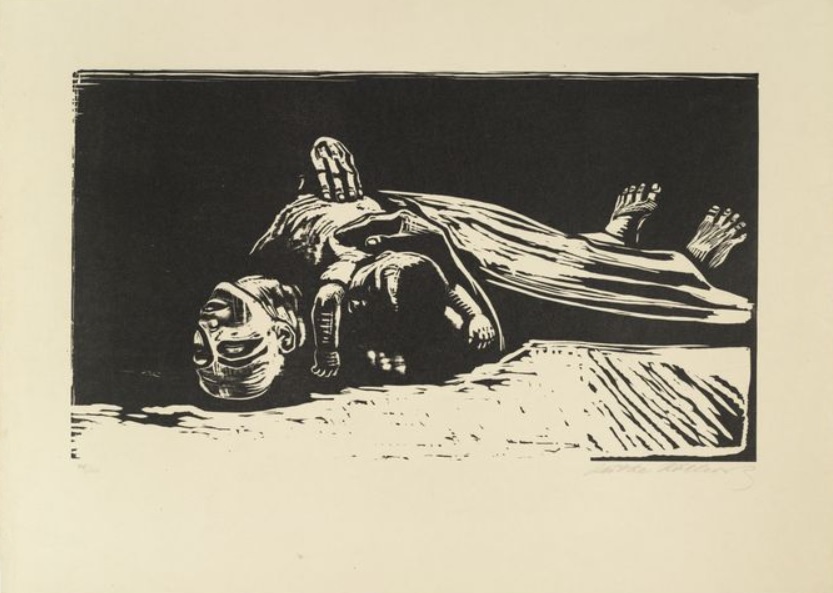

"The Widow II" (Die Witwe II) woodcut, 1922. Kollwitz's work focused on the vulnerable members of society, like widows, children, and even the working class, affected by social traumas, particularly WWI. Learn more. © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

"The Widow II" (Die Witwe II) woodcut, 1922. Kollwitz's work focused on the vulnerable members of society, like widows, children, and even the working class, affected by social traumas, particularly WWI. Learn more. © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, BonnOrwell’s point on the limiting nature of hunger is well-taken.

“When you are approaching poverty,” Orwell continues, “you make one discovery which outweighs some of the others… you discover the great redeeming feature of poverty: the fact that it annihilates the future.”

Imagine being trapped not only in a body, a hungry body at that but in the hideous, eternal present. An annihilated future means no agents of the future, like dreams, hope, or even imagination — the comfort that comes from slices of abstract thought that brighten our mind’s daily log — do not exist.

What must it be like to exist without hope, dreams, or imagination?

“The stomach alone is measuring time,” writes Elie Wiesel in his horrifyingly true story of imprisonment in Auschwitz. Wiesel witnessed the limits of human suffering and humanity and, years later, instructed the world on the nature of hunger and deprivation.

A few days after my visit, the dentist’s office was shut down. He had been thrown into prison and was about to be hanged. It appeared that he had been dealing in the prisoners’ gold teeth for his own benefit. I felt no pity for him. In fact, I was pleased with what was happening to him: my gold crown was safe. I could be useful to me one day to buy something, some bread, or even time to live. At that moment, all that mattered to me was my daily bowl of soup, my crust of stale bread. The bread, the soup – those were my entire life. I was nothing but a body. Perhaps even less: a famished stomach. The stomach alone was measuring time.

From Elie Wiesel’s Night

The all-encompassing nature of extreme hunger is even more evident when Wiesel discusses Auschwitz’s liberation: “Our first act as free men was to throw ourselves onto the provisions. That’s all we thought about. No thought of revenge or parents. Only of bread.”

“You’ve got to have something to eat…,” echoed singer Billie Holiday beautifully, who was scratching a barely sustainable living in Manhattan around the same time that Wiesel was forced into the form of a walking corpse.

I’ve been told that nobody sings the word ‘hunger’ as I do. Or the word ‘love.’ Maybe I remember what those words are all about. Maybe I’m proud enough to want to remember Baltimore and Welfare Island, the Catholic institution and the Jefferson Market Court, the sheriff in front of our place in Harlem and the towns from coast to coast where I got my lumps and my scars, Philly and Alderson, Hollywood and San Francisco – every damn bit of it.

All the Cadillacs and minks in the world – and I’ve had a few – can’t make it up or make me forget it. All I’ve learned in all those places from all those people is wrapped in those two words. You’ve got to have something to eat and a little love in your life before you can hold still for any damn body’s sermon on how to behave. Everything I am and everything I want out of life goes smack back to that.

From Billie Holiday’s Lady Sings the Blues

Holiday’s extraordinary life only stretched forty-four years, which suggests a literal meaning of Orwell’s “future annihilation.”

What about the heart-crushing lines in David Wojnarowicz’s tender, sharp memoir where he suggests that in poverty, he was at least able to sell his body as a means to sustain himself? In contrast, individuals in extreme poverty couldn’t even do that.

There were times in my teens when I was living on the streets and selling my body to anyone interested. I hung around a neighborhood so crowded with homeless people that I can’t even remember what the architecture of the blocks looked like. Whereas I could at least spread my legs and gain a roof over my head, all those people down in those streets had reached the point where the commodity of their bodies and souls meant nothing more to anyone but themselves.

From David Wojnarowicz’s “In the Shadow of the American Dream” in Close to the Knives

What remains if hunger subverts our intellect, renders our body a worthless commodity, and destroys any temporary flight from our corporal self?

Indeed not time; Wiesel showed us that.

Love, empathy, compassion? A person is not a person when he’s hungry, noted Orwell: “You discover that a man who has gone even a week on bread and margarine is not a man any longer, only a belly with a few accessory organs.”

Remember Holiday: “Everything I am goes back to that….”

So, what does he become in this vertiginous existence? He is more than impoverished; he is human-deprived. How do we not simply protect and care for him, but understand him?