"All really inhabited space bears the essence of the notion of home."

What is the feeling of home? Rainer Maria Rilke once excused himself for not writing in a while by saying, “I haven’t had that feeling of home in which to write.” What a curious thing to say.

I aim for discipline and routine but sometimes I go days, weeks without writing here, blocked by what I would call fear, but perhaps it is simply homesickness? Lacking the feeling of home? The things we say and write are little vessels of self flung into the world, in that way we inhabit our words. A need to feel at home in one's self-expression certainly makes sense. But what does home feel like?

Do Rilke and I mean the same thing?

A deep human need to “feel at home” exists across languages and epochs.

“You rush hither and thither with the idea of dislodged a firmly seated weight when the very dashing about just adds to the trouble it causes you. […] Once you have rid yourself of the affliction there, though, every change of scene will become a pleasure. You may have banished to the ends of the earth, and yet in whatever outlandish corner of the world you may find yourself stationed, you will find that place, whatever it may be ink, a hospital home.”

From Seneca’s Letters From a Stoic

It is the same sense of home in which Peter Mayle writes about his beloved, adopted Provence in both A Year in Provence and Encore Provence.

A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community, which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future. This participation is a natural one, in the sense that it is automatically brought about by place, conditions of birth, profession and social surroundings. Every human being needs to have multiple roots. It is necessary for him to draw well-nigh the whole of his moral, intellectual and spiritual life by way of the environment of which he forms a natural part.

From Simone Weil’s The Need for Roots

Three decades later, fellow French philosopher Gaston Bachelard amended the concept with a notion that our need for “home” is for inhabited space, including space we realize through imagination.

[A]ll inhabited space bears the essence of the notion of home. […] the imagination functions in this direction whenever the human being has found the slightest shelter: we shall see the imagination build ‘walls’ of impalpable shadows, comfort itself with the illusion of protection — or, just the contrary, tremble behind thick walls, mistrust the staunchest ramparts. In short, in the most interminable of dialectics, the sheltered being gives perceptible limits to his shelter. He experiences the house in its reality and in its virtuality, by means of thought and dreams.

From Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space

Home is not always what we envision in our heads - walls and a ceiling perhaps - but maybe those are the most basic components because they give warmth, shelter and rest. In 1845, American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau walked out of urban society to a distant wood where he constructed a four-walled building with a bed, chair, and fireplace. Thoreau’s physical and imaginative attachment to the space turned it from shelter to home.

I lingered most about the fireplace, as the most vital part of the house. Indeed, I worked so deliberately that though I commenced at the ground in the morning, a course of bricks […] served as my pillow at night; […] When I began to have a fire at evening, before I plastered my house, the chimney carried smoke particularly well, because of the numerous chinks between the boards. Yet I passed some cheerful evenings in that cool and airy apartment, surrounded by rough brown boards full of knots, and rafters with the bark on high overhead.

My house never pleased my eye so much after it was plastered, though I was obligated to confess that it was more comfortable. […] I now first began to inhabit my house, I may say, when I began to use it for warmth as well as shelter.

From Henry David Thoreau’s Walden

That Thoreau focused on the fireplace not simply for heat but for hearth is indicative of the very basics of what "home" means. The hearth symbolizes calm, consistency, a knowable order, and a nurturing warmth. “My preferred working state is thermal,” notices legendary dance choreographer Twyla Tharp, “I need heat… it calls up the warmth of the hearth and home… which is all about feeling safe and secure.”

“In our less communal age of central heating and separate rooms for each family member,” muses Stephen Fry in his witty and rascally retelling of Greek myths, “we did not lend the hearth quite the importance that our ancestors did.”

Of all the gods, Hestia […] is probably the least well known to us, perhaps because the realm that Zeus, in his wisdom appropriated to her was the hearth. In our less communal age of central heating and separate rooms for each family member, we did not lend the hearth quite the importance that our ancestors did […]. Yet, even for us, the word stands for something more than just a fireplace.

We speak of ‘hearth and home’. The word ‘hearth’ shares its ancestry with ‘heart,’ just as the modern Greek for ‘hearth’ is kardia, which also means ‘heart.’ In ancient Greece the wider concept of hearth and home was expressed by oikos, which lives on for us today in words like ‘economics’ and ‘ecology’. The Latin for hearth is focus — which speaks for itself. It is a strange and wonderful thing that out of the words for fireplace we have spun ‘cardiologist’, ‘deep focus’ and ‘eco-warrior.’ The essential meaning of centrality that connects them also reveals the significance of the hearth to the Greeks and the Romans, and consequently the importance of Hestia, its presiding deity.

From Stephen Fry’s Mythos

The necessity of a hearth as an aspect of the “feeling of home” becomes clear when we ask: What happens to a home without a hearth? A home without warmth?

Unease and unrest, according to Robert Lowell’s mid-century writing.

Lowell also suffered, like I do, from manic-depressive disorder and was hospitalized several times at McLean outside Boston. So was I. He remembered blue. I remembered orange.

During the weekends I was at home much of the time. All day I used to look forward to the nights when my bedroom walls would once again vibrate, when I would awake with rapture to the rhythm of my parents arguing, arguing one another to exhaustion. Sometimes, without bathrobe or slippers, I would wriggle out into the cold hall on my belly and ambuscade myself behind the banister. I could often hear actual words. ‘Yes, yes, yes,’ Father would mumble. He was ‘back-sliding’ and ‘living in a fool’s paradise of habitual retarding and retarded do-nothing inertia.’ […] She was hysterical even in her calm. One night she said with murderous coolness, ‘Bobby and I are leaving for Papa’s.’ This was an ultimatum to force Father to sign a deed placing the Revere Street house in Mother’s name.

From Robert Lowell’s Life Studies

Lowell suffered complete alienation from the hearth of his childhood home; he is cold, dark, and surrounded by violence and chaos. That watchful child was toppled by depression, even psychosis as an adult — both acute mental and emotional rootlessness.

Or consider the rootlessness of jazz singer Billie Holiday. Born when her mom was thirteen, Holiday lived with her mother at her mother’s job, then in a strict Catholic girls’ school, then a brothel, and in hotels while touring with the band (hotels that barred her entering through the front, although she was the star singer), and, repeatedly, she “lived” in jail.

In each of these “homes,” Holiday is slapped with prejudice, trauma, and a complete lack of love and security. She is constantly reminded of her undesirable, unwanted, and misunderstood status as a poor, Black female.

You’re always under pressure. You can fight it but you can’t kick it. The only time I was free from this kind of pressure was when I was a call girl as a kid and I had white men as my customers. Nobody gave us any trouble. People can forgive people any damn thing if they did it for money.

From Billie Holiday’s Lady Sings the Blues

Comedian John Cleese called home “the place you do not have to strive.” Holiday and the many millions who are rootless, disenfranchised, and alienated never had a place to stop striving.

“You can be up to your boobies in white satin, with gardenias in your hair and no sugar cane for miles,” warned Holiday, “but you can still be working on a plantation.”

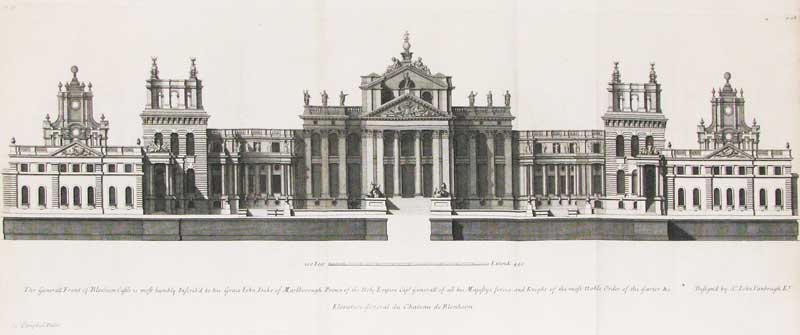

Colen Campbell’s engraving of Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire. Blenheim is the seat of the Duke of Marlborough and the birth and burial place of Winston Churchill. The Palace and its gardens, designed by Capability Jones, are still inhabited by the Spencer-Churchills. Print from Isaac & Ede Collection.

Colen Campbell’s engraving of Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire. Blenheim is the seat of the Duke of Marlborough and the birth and burial place of Winston Churchill. The Palace and its gardens, designed by Capability Jones, are still inhabited by the Spencer-Churchills. Print from Isaac & Ede Collection.Holiday’s writings remind us that home is not and cannot be a physical space for many people.

We see this with singers Patti Smith and artist Robert Mapplethorpe. When they were both young, poor, and mercurial, they created a home in the company of each other. In a nurturing embrace, their loneliness met. Smith writes: “In this space between us, home.”

Is there anyone in whose company you feel a feeling of home?

During the war and throughout life, Roald Dahl put himself in a “feeling of home” by writing to his mother. His light lines (“There is nothing very wrong with me. I’ve merely had a severe concussion”) and dancing prose (“All these things and many more I shall derive the greatest pleasure from doing”) seemed to say, “The war might be raging out there, and there is a woefully inadequate plane waiting to take me skyward, but for this moment I’m with my mother. I’m next to the hearth.”

Dahl wrote to his mother each day he was on active duty.

When I rethink “I wasn’t in the feeling of home,” what I meant — and likely Rilke as well — was “I haven’t been myself.” I haven’t been home within myself. The first and last place of home.

I think of “home” as less of a space and more of a feeling. In that way, I inhabit myself. That is a lovely thought. Let’s sit next to it. Soothe yourself, hug yourself. You are, quite literally, home.

: ('/assets/1/6/bundles/sitetheorycore/images/shapeholder-square.png?v=1773139254') }})

}})

: ('/assets/1/6/bundles/sitetheorycore/images/shapeholder-square.png?v=1773139254') }})

? ('sitetheorycore/images/shapeholder-' + _.get(model.data, 'version.meta.ratio') + '.png' | assetPath) : ('sitetheorycore/images/shapeholder-' + _.get(model.data, 'version.imageRatio') + '.png' | assetPath) ) }})

: (model.data.version.imageRatio === 'natural' ? model.data.version.images[0]._thumbnailUrl : '/assets/1/6/bundles/sitetheorycore/images/shapeholder-square.png?v=1773139254') }})