"As many as a dozen species may burst their buds on a single day. No man can heed all of these anniversaries; no man can ignore all of them."

Prairie and field flowers have the distinction of being rather immemorable individually and extraordinary collectively. There is no noun for their collective bloom (besides 'bloom' itself), but there should be. Prairies, fields, and meadows are the gestalt agents of the flower world.

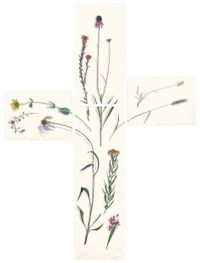

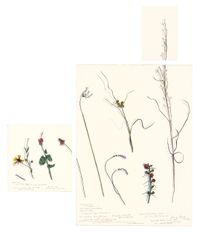

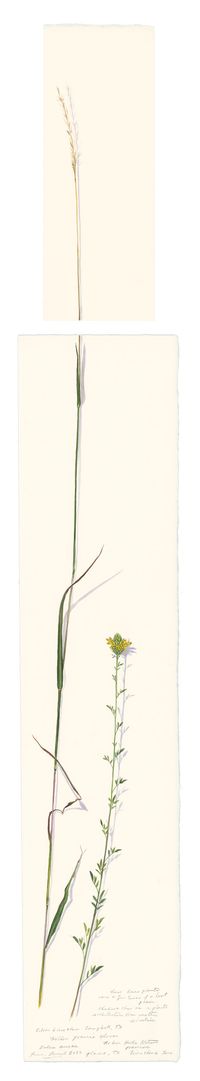

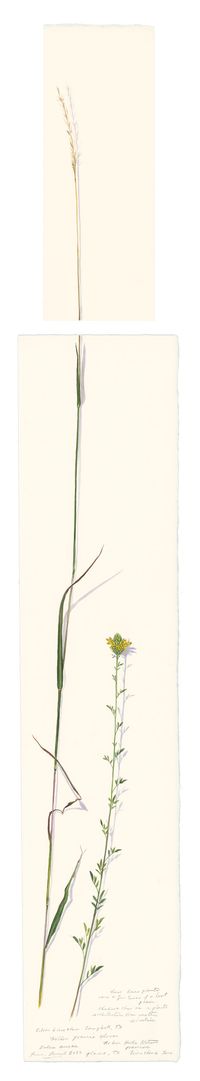

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.:

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.:They also testify to nature's resilience and resistance to human spoiling. Prairie and meadow flowers are the ones we overlook and neglect, the ones that come without us, unpropagated, unplanted, and even unexpected. The opposite of gardens (although gardens offer their own soul-soothing work).

Prairie flowers (and their cousins in the meadows and fields) are the ones that come in spite of us. American writer and naturalist Leopold Aldo (January 11, 1887 – April 21, 1948) noted this human-independent feat in his 1940s journals: "As many as a dozen species may burst their buds on a single day. No man can heed all of these anniversaries; no man can ignore all of them."

During every week from April to September there are, on the average, ten wild plants coming into first bloom. In June as many as a dozen species may burst their buds on a single day. No man can heed all of these anniversaries; no man can ignore all of them. He be hauled up short by who steps unseeing on May dandelions may August ragweed pollen; he who ignores the ruddy haze of April elms may skid his car on the fallen corollas of June catalpas. Tell me of what plant-birthday a man takes notice, and I shall tell you a good deal about his vocation, his hobbies, his hay fever, and the general level of his ecological education.

Leopold's A Sand Country Almanac, published in 1949 while the author was physically adjacent, if not surrounded, by such a bloom, is a gentle reminder that we are made from the earth and will return to it.

Aldo Leopold.

Aldo Leopold.Leopold's record is also a foundational text to the existence of wildlife in his space and time. He wrote as a witness: waking to the birds (and counting them), closing with the sun (and timing its fall), spying wild-flowers (and planting them) and expanding his eyes to the changing daily beauty of his rural Midwest American landscape.

Every July I watch eagerly a certain country graveyard that I pass in driving to and from my farm. It is time for a prairie birthday, and in one corner of this graveyard lives a surviving celebrant of that once-important event. It is an ordinary graveyard, bordered by the usual spruces and stuffed with the usual pink granite or white marble headstones... Heretofore unreachable by scythe or mower, this yard-square relic of original Wisconsin gives birth, each July, to a man-high stalk of Silphium.

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie."No man can heed all of these anniversaries; no man can ignore all of them," Leopold noted. And yet humans were doing exactly that during Leopold's time and certainly since then.

This year I found the Silphium in first bloom on 24 July, a week later than usual: during the last six years the average date was 15 July. When I passed the graveyard again on 3 August, the fence had been removed by a road crew, and the Silphium cut. It is easy now to predict the future; for a few years my Silphium will try in vain to rise above the mowing machine, and then it will die. With it will die the prairie epoch. The Highway Department says that 100,000 car pass yearly over this route during the three summer months when the Silphium is in bloom. In them must ride at least 100,000 people who have 'taken' what is called history and perhaps 25,000 who have 'taken' what is called botany.

This nature-metered measure of specimens, even in 1949, would become a reference point to the human and seasonal changes to come. Most notable are the environmental changes from the industrialisation of farming, the need for roads and transformational highway systems.

The shrinkage in the flora is due to a combination of clean farming, woodlot grazing, and good roads. Each of these necessary changes of course requires a larger reduction in the acreage available for wild plants, but none of them requires, or benefits from the erasure of species from whole farms, townships, or counties. There are idle spots on every farm, and every highway is bordered by an idle strip as long as it is; keep cow, plow, and mower out of these idle spots, and the full native flora, plus dozens of interesting stowaways from foreign parts, could be of the normal environment of every citizen.

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.In her radical 1962 book Silent Spring, biologist Rachel Carson publicized the harm of such chemicals on the cellular level of life. However, federal changes to fertilizers and insecticides would not happen in America until the 1970s. The over-mowed and overburdened plants that grow adjacent to the newly cleared acreage of American farmland and the wide shoulders of the interstate highway system were and are still affected.

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.The natural devastation Leopold saw on a distant horizon surrounds us today. Even the word 'nature' cannot be brought over our tongues and lips without giving equal time to its devastating decline, 'what once was.' The steady drop, the vanishing, the absence. Leopold's subtle fears are manifest. To illustrate some of the dainty beauties that collectively form the prairie flowering, I asked artist and naturalist James Prosek for images from his 2024 Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie. Prosek's meticulous drawings, all done outside in Texas Hill Country prairie (for non-Americans, Texas is about 1,200 miles southwest of Leopold's Wisconsin but the prairies are ecologically similar) are a witness statement to the status of life in the prairie, the places that form without us and yet respond to us. (He's also illustrated unexpected creature migrations).

Both Prosek and Leopold worked from the field, although for slightly different purposes. Leopold wrote Sand Country Almanac to support his efforts as a farmer. That was, after all, the original intention behind all almanacs — environmental observation and crop predictability. Yet today, this kind of record keeping - visually like Prosek or textually like Leopold - is not only for farmers but ecologists, environmentalists, and lay people like myself. Because let's face it, we are all involved in the annual prairie flowering. "No man can ignore all of them", Leopold wrote, and surely he meant for its beauty. Sadly now, we must notice it for life itself, a harbinger of a grim future.

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.

Texas Prairie Flowering, 2024. Painting by James Prosek from his book Grasslands: Painting the American Prairie.In today's context, is Leopold's work a celebration or elegy? Sadly both, as is everything written or drawn of nature. But there is sustenance in the fact that individuals like Leopold and Prosek and likely you, dear Reader, who notice what is around them and shout: "Look at this subtle brilliance; it matters!" We might not all live by prairies, but can you find a meadow or a field in your environment? A space in which nature, against all we do to it, is trying to matter? What million different things are happening there?

Here are a few more who live with the land, I mean with it in the everyday: facing it, touching it, hearing it, and working it. People like Kentucky farmer and poet Wendell Berry, life-long forager John Wright, printmaker Angela Harding, and poet J. Drew Lanham are a celebrated group on The Examined Life. They represent some idealism (utopia presumes nature, doesn't it?) that taps into an ancient covenant we've forgotten: we must work with nature, not against it (to borrow from Carson).