"At some point in their lives, nearly all creatures on earth make a journey from one place to another."

"A pigeon's sense of home is local and distinct," writes pigeon owner Jon Day in a rare book on pets, family, and the complex nature of home. "It is a place rather than an environment. In this, they are very much like us." A pigeon's homing instinct means that pigeons can be taken hundreds of miles away from their home and will return without any directional assistance.

Such a dominant and necessary instinct that overcomes all sense might be difficult for humans to imagine, even if we have a concept of "home" and its gravity (and sometimes alienation) but let's expand that further. What about animals that return - routinely and instinctively - to a place that not only is not home but is a place they have never even been?

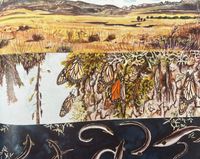

"One of the most remarkable things about the migration of the monarch butterfly is that the butterflies that fly to Mexico have never been there before," writes James Prosek (Born in 1975) in one of his first books Bird, Butterfly, Eel. Prosek is one of America's leading wildlife, illustrators and conservationists, an artist whose work I greatly admire. Prosek's illustrations are precise without being caught in a realism trap that makes them inaccessible. The inspiration for Bird, Butterfly, Eel, came from Prosek's close observations of the animals in his native New England.

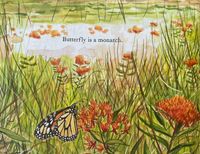

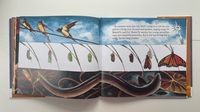

The idea for this book grew out of my passion for the host plant of the monarch butterfly, the milkweed - in particular, Asclepias tuberosa, commonly known as butterfly weed. Adult monarchs will lay their eggs on any of the hundred or so species of milkweed, where caterpillars hatch, eat the plant, grow, and spin themselves into a jeweled green case called a chrysalis. Several years ago I transplanted some butterfly weed plants to a sunny part of the front yard. Soon after, the butterflies started to lay their single white eggs on the leaves and flower buds of the plants. I found that dozens of caterpillars had hatched and were feeding on the milkweed. Monarch butterflies continued to emerge.

Prosek's butterflies and millions more, born in the late summer of the Northern United States, would, come November, begin to fly more than three thousand miles south to their Mexican breeding ground. This is not a homing instinct, but migratory. "One of the most remarkable things about the migration of the monarch butterfly is that the butterflies that fly to Mexico have never been there before."

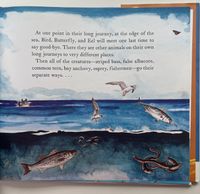

The animals Prosek chose to illustrate - bird, butterfly, and eel - are all native to a small pond in New England. Their migratory areas, two by air and one by sea: are Patagonia, Mexico, and the wide Sargasso Sea. These three exceptional animals, each migratory, each possessing some instinctive ability, perhaps connected to the earth's magnetism, to follow in the path of genetic demand.

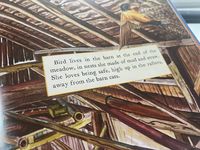

While the monarch butterflies travel to Mexico, barn swallows fly south more than ten thousand miles to South and Central America and then return to North America to the same nest they built the previous season.

Bird lives in the barn at the end of the meadow, in nests she made of mud and straw. She loves being safe, high up in the rafters, away from the barn cats.

The mystery of migration seems so visible now, but consider: one hundred years ago, how would anyone know where these birds went and what they were doing? How amazing to know only that an entire species would merely leave and then return in patterns as old as the species itself.

People guessed that the swallows transformed into other creatures, or buried themselves in the mud at the bottom of freshwater ponds. Eventually, these myths were dispelled, in part by banding, or tagging, which taught us that some birds return in spring to the same nest. Later, improved tagging technology allowed us to track the swallows' path to their winter ground.

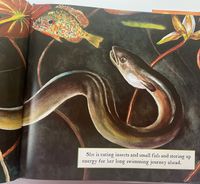

The third animal Prosek includes is the American eel. Uniquely in this group, the eel has rich, complex needs that we do not fully understand. Not only does the eel live and survive in both salt and fresh water, but it also travels more than fifteen thousand miles to a point in the ocean known as the Sargasso Sea, a warm, watery gyre in the Atlantic Ocean. Despite all that knowledge we have on the American eel, Prosek reminds us no human has ever seen an eel spawning in the wild.

After the eel spawns in saltwater, the egg-hatched larva called leptocephali drift until they latch on to sargassum weed and are carried from the Sargasso sanctuary to the coast, turning into recognizable eels along the way. After about a year of drifting and swimming, the adult eels return to freshwater ponds and rivers until they too heed a call to migrate and spawn their little eels.

The connection between the animals Prosek features in this book is really about a beautiful relationship between movement and home. Movement and migration - especially on the human level - ultimately become an issue of survival and home.

Prozek illustrates this lucidly:

At some point in their lives, nearly all creatures on Earth make a journey from one place to another. Sometimes they travel to find food, and sometimes to meet up with other creatures like themselves. This kind of movement, through the air, under water, over land, is called migration. Some birds and fish make short migrations of a few hundred feet, such as from a lake to an inlet stream, and some migrate as far as thousands of miles, from one hemisphere to the other.

When one's living patterns span continents, does one's concept of home span as well? Or does it mean that there is no home? What does it feel like to not have a geographical home? During World War II, France's oppositional government asked philosopher Simone Weil to advise them on how to support soldiers returning from war. Weil wrote a deeply humane treatise on rootedness as "one of the deepest needs of the soul." To be connected to a place, and then removed from that place, are issues facing so many people - and will continue to - across the globe. The movement of people and animals leaves tracks and trails for subsequent generations to follow.

Read more from Robert MacFarlane on the paths we make and what they make of us, Una Marson's poetic reconciliation of homeland and adopted land, Ocean Vuong's search for personhood without homeland, and my look at what we mean when we talk about "home." And then imagine what month it is, and what the bird, butterfly, and eel are doing at this exact moment.