"The geometry of this city's architectural perspective is perfect for losing things forever."

"I'd never possess this city," Russian poet Joseph Brodsky (May 24, 1940 - January 28, 1996) wrote of his beloved Venice, "But then I'd never had any such aspiration." Brodsky writes about Venice as a space that welcomes him with familiarity yet gives him longed-for anonymity. He visited Venice often, and there is a plaque in his name.

The place of childhood forms consciousness. "I believe that one carries the shadows, the dreams, the fears and dragons of home under one’s skin," wrote Maya Angelou in her first memoir of childhood. A city is part of our "home," and it imprints on us. Do we make an impact on it?

When Brodsky writes about St. Petersburg, the city of his birth and near death, he uses a demonstrably different tone: intellectually detached, cynical, and even depressive. Yet there is that same undercurrent of longing.

Joseph Brodsky in Leningrad.

Joseph Brodsky in Leningrad.Brodsky was born in 1940 in what was then Leningrad. He remembered pictures of Comrade Lenin everywhere. He and his family suffered ill health and chronic hunger during Germany's four-year siege of Leningrad. They were ostracized from traditional work and community because of their Judaism. In 1972 Brodsky, already punished for his "parasitism" and anti-Soviet poetry, was exiled from the city and country entirely. He never saw his family or the mother of his child again. He wrote freely and independently in the United States but never returned to his home country.

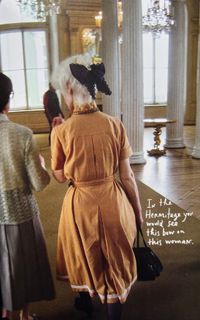

"I went to the Hermitage and saw this bow on this woman," observed illustrator Maira Kalman of St. Petersburg in 2007.

"I went to the Hermitage and saw this bow on this woman," observed illustrator Maira Kalman of St. Petersburg in 2007.In his essay A Guide to a Renamed City, Joseph Brodsky casts an intellectual gaze on the three-hundred-and-twenty-year-old city in the context of its two remarkable leaders, Lenin and Peter the Great, who tried everything to 'possess' the city.

In front of the Finland Station, one of five railroad terminals through which a traveler may enter or leave this city, on the bank of the Neva River, there stands a monument to a man whose name this city presently bears. In fact, every station in Leningrad has a monument to this man, either a full-scale statue in front of or a massive bust inside the building. But the monument before the Finland Station is unique. It's not the statue itself that matters here, because Comrade Lenin is depicted in the usual quasi-romantic fashion, with his hand poking into the air, supposedly addressing the masses; what matters is the pedestal. For Comrade Lenin delivers his oration standing on the top of an armored car. It's done in the style of early Constructivism, so popular nowadays in the West, and in general the idea of carving an armored car out of stone smacks of a certain psychological acceleration, of the sculptor being ahead of his time. As far as I know, this is the only monument to a man on an armored car that exists in the world. In this respect alone, it is a symbol of a new society.

Lenin was - and is - a complicated, even mythical figure for early 20th-century Russians. He freed society from the monarchy yet ushered in an authoritarian system that systematically delivered death or exile to its opponents.

[A]ppropriately enough, a couple of miles downstream, on the opposite bank of the river, there stands a monument to a man whose name this city bore from the day of its foundation: Peter the Great. This monument is known universally as the "Bronze Horseman," and its immobility matches only the frequency with which it has been photographed. It's an impressive monument, some twenty feet tall, the best work of Etienne-Maurice Falconet, who was recommended by both Diderot and Voltaire to Catherine the Great, its sponsor. Atop the huge granite rock dragged here from the Karelian Isthmus, Peter the Great looms on high, restraining with his left hand the rearing horse that symbolizes Russia, and stretching his right hand to the north.

These two individuals stamped their existence on St. Petersburg, but their legacy, Brodsky supposes, can be summarized in statues. Statues that stand in the shadows of people who never existed, like Dostoevsky's characters (when I visited St. Petersburg, it was to pace the streets like Raskolnikov).

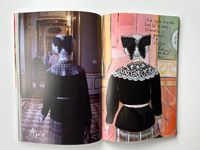

"Again," Kalman notes, she saw the same bow on the same woman in a different place, giving us a sense of her journey around the city.

"Again," Kalman notes, she saw the same bow on the same woman in a different place, giving us a sense of her journey around the city.Brodsky continues to reduce the glamorized past to a harsh truth, these men were less than their laudatory statues suggest:

When a visionary happens also to be an emperor, he acts ruthlessly. The methods to which Peter I resorted, to carry out his project, could be at best defined as conscription. He taxed everything and everyone to force his subjects to fight the land. During Peter's reign, a subject of the Russian crown had a somewhat limited choice of being either drafted into the army or sent to build St. Petersburg, and it's hard to say which was deadlier. Tens of thousands found their anonymous end in the swamps of the Neva delta, whose islands enjoyed a reputation similar to that of today's Gulag.

We all have memories of place. Brodsky asks: do places have a memory of us? In St. Petersburg, Brodsky was born, almost died, certainly suffered, found love, and had a child. He wielded this milieu to write poetry of such intense, intellectual honesty that the same city banished him entirely. Critics note the deeply depressive note in Brodsky's writing; it is found here.

This city really rests on the bones of its builders as much as on the wooden piles that they drove into the ground. So does, to a degree, nearly any other place in the Old World; but then history takes good care of unpleasant memories. St. Petersburg happens to be too young for soothing mythology; and every time a natural or premeditated disaster takes place, you can spot in a crowd a pale, somewhat starved, ageless face with its deep-set, white, fixed eyes, and hear the whisper: "I tell you, this place is cursed!" You'll shudder, but a moment later, the face is gone when you try to take another look at the speaker. In vain, your eyes will search the slowly milling crowds, the traffic creeping along: you will see nothing except the indifferent passersby and, through the slanted veil of rain, the magnificent features of the buildings. The geometry of this city's architectural perspective is perfect for losing things forever.

The main thing we lose forever, as individuals and as a collective, is memory. When we lose memory, we lose the truth.

When I was in St. Petersburg two decades ago, there were anti-Putin protests. Initially, they were squared away behind fencing, but then the crowd shifted and started to move, shout, and run. When it engulfed commuter trams, the passengers banged windows to get out. I ducked into an alcove, overwhelmed with empathy with the protestors, the people stuck on the trains, and even the preposterously juvenile soldiers conscripted to keep order, their shoulders not yet widened to fit the overcoat.

How brave and bold everyone was, independent and invincible in the manner of Brodsky.

A white night is a night when the sun leaves the sky for barely a couple of hours-a phenomenon quite familiar in the northern latitudes. It's the most magic time in the city when you can write or read without a lamp at two o'clock in the morning, and when the buildings, deprived of shadows and their roofs rimmed with gold, look like a set of fragile china. It's so quiet around that you can almost hear the clink of a spoon falling in Finland. The g transparent pink tint of the sky is so light that the pale-blue watercolor of the river almost fails to reflect it. And the bridges are drawn up as though the islands of the delta have unclasped their hands and slow begun to drift, turning in the mainstream, toward the Baltic. On such nights, it's hard to fall asleep, because it is too light and because any dream will be inferior to reality. Where a man doesn't cast a shadow, like water.

Like Lenin or Peter the Great, one might shape a city in one's likeness, name streets, and erect statues. Even Joseph Brodsky is commemorated by a plaque in Venice. But we cannot immortalize ourselves in physical space. As more and more of us dwell not in cities but in the ever-perfecting, ever-automating world online - what will be remembered of us?

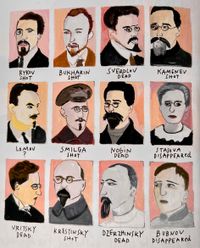

Russian Intellectuals and politicians, as illustrated by Maira Kalman.

Russian Intellectuals and politicians, as illustrated by Maira Kalman.Writing, art, and literature cast a shadow. Art speaks truth of human existence that exists outside memory. I pulled illustrations from Maira Kalman's sublime meander through the streets of her homelands (Russia and New York City) to accompany Brodsky's observations. Kalman has ancestral ties to Russia; her mother was born in Belarus. Her wondrous work expands our understanding and capacity for compassion. I'd like to return to St. Petersburg and read Brodsky and Kalman on the street.

Read more on connection and anonymity in Olivia Liang's compilation of artists forgotten and found on the streets of New York, poet Grace Paley on the human connectedness that gives a city its soul, and one of my earliest articles on our metaphysical location post-death.