"What do women hold? The home and the family. And the children and the food. The friendships. The work. The work of being human."

I find this article difficult to write because it hits home. I thought I’d begin by listing some of the things I think I hold as a woman, but I was interrupted by someone in the house asking me where we keep the tape dispenser. One of the things I hold: the current location of every single item in the house at all times.

Maira Kalman (born 1949) is one of my favorite visual authors. Her illustrated book Women Holding Things will immediately strike a chord with many of you, or it will open your mind - as Kalman does in her signature way - to the constant, cognitive burdens women hold. What do women hold? She asks, unprepared to let us assume anything,

The home and the family.

And the children and the food.

The friendships.

The work.

The work of the world.

And the work of being human.

The memories.

And the troubles and the sorrows

and the triumphs.

And the love.

Men do as well,

but not quite in the same way.

Kalman has a way of directing our gaze and the universal in the everyday. When she follows humans on the streets of New York, with a watchful eye and a spritely pen, she demonstrates how empathy is born from observation. Her search for meaning and cohesion in the bright light of America was formed by one interaction after another with Americans and the places they hold holy. Even her charming, illustrated version of the classic The Elements of Style parsed E. B. White's deft writing advice to a word-by-word level.

"Maira Kalman" by Natasha Rauf for The Examined Life.

"Maira Kalman" by Natasha Rauf for The Examined Life.Women Holding Things is not a tally of what women hold relative to men; it is a gentle, compassionate nod at the genderized roles of what is held and expected to be held, in hopes that we might improve upon it, or at the very least, acknowledge it.

Sometimes, when I am feeling

particularly happy or content,

I think I can provide sustenance

for legions of human beings.

I can hold the entire world in my arms.

Other times, I can barely cross the

room. And I drop my arms. Frozen.

Kalman uses the word frozen, and while I appreciate the water metaphor, I sometimes feel like I am drowning. To be frozen suggests immobility; to be immobile is no longer actively holding, which is impossible. Impossible because there is no one else to hold the memory of the tape dispenser's location. Never mind the morality of the children, or the kindness to strangers, or the memory of things.

Or is there?

I am brought back to

my grandmother,

my mother, my aunts,

my sister, my daughter,

my granddaughters,

my cousins.

The women who

are my friends.

It is tricky business, being a woman. Part of this exceptional line of other women who understand what you hold but simultaneously apply their standards and methods of survival to your own. How can I lean on others who are also drowning? No, it is not that simple; in this vast network of genetic and gender continuation comes support.

We have spoken to each other for thousands of hours.

About all that can be held.

And not held.

And how sometimes

the water runs through our fingers.

And how sometimes

the cakes are baked

and the beds are made.

And the books are written.

The bed

and the books

and the cakes.

In my case, it is good to hold all.

"My grandmother (in pearls) holding the weight of the world on her shoulders her legs as big as tree trunks."

"My grandmother (in pearls) holding the weight of the world on her shoulders her legs as big as tree trunks."Once again, Kalman directs us away from the immensity of the thing, the universal magnitude of weight, and returns us to one true thing: "Holding a specific thing is a very nice thing to do..." What if we were to hold that one thing, very close, very tight, or high and dry, and simply do that for a moment? Imagine.

"Woman holding a pink ukelele under a giant cherry tree."

"Woman holding a pink ukelele under a giant cherry tree."And it need not be a warm, comforting holding; as Kalman reminds us, there is pleasure in the holding, especially when holding is love (although, isn't all holding love?).

"Woman walking down the street holding her sick dog."

"Woman walking down the street holding her sick dog."There is a unique holding that comes to mothers, the holding of another being - from before they are born - until long, long after we exist in memory. We create a space for that child that is within us, always within, to which they can return their entire lives. Although they rarely do after a time. And then we must hold that sadness.

"Woman holding, consoling, and comforting her daughter."

"Woman holding, consoling, and comforting her daughter." "Girl holding doll and book."

"Girl holding doll and book." "Woman holding red balloons walking through the park."

"Woman holding red balloons walking through the park."I used a silly example of a tape dispenser, but many of the things we hold are domestic, "the home and the family" is the first line of this book. Domestic is not merely "of the home." It has come to mean comfort, utility, and even - as illustrated in my particular favorite "woman holding shears" - beauty.

"Woman holding shears."

"Woman holding shears."Who will hold up beauty if not I? On the most mundane, simple level - an organized shelf perhaps. A herbaceous border. Among all this, we must hold ourselves. In readiness, in strength, in emotional deprivation. There is time for moods, perhaps, but nothing greater than that.

"Woman holding on to terrible mood from bad dreams the night before."

"Woman holding on to terrible mood from bad dreams the night before."Holding strong, bodies that defy, is a thing to be marveled at and appreciated. Holding it all together at once.

"Woman holding her hip."

"Woman holding her hip."In 1929, long ago in terms of many things, Virginia Woolf argued a woman needed money and room of her own to reach her full, creative potential. Her thesis is relevant today, despite being long ago in terms of many things, because the heart of her speech was one's need for space away from the world's neediness, physically or cognitively. A cone of light where memory can meet consciousness in the dark, Annie Dillard, (of course, a woman) called it. Do men ever write about such things? Finding space and autonomy to write?

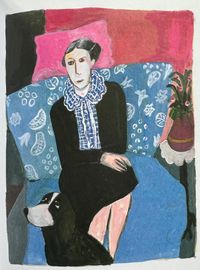

"Virginia Woolf barely holding it together."

"Virginia Woolf barely holding it together."A space to set down our wares - as lovely or nice as they might be - shake everything off and pick up something else, or nothing. Where we no longer fear being interrupted or letting anyone down. Where we can chase that illuminating spiral of thought and creation as far as it goes. I cannot do the best job I want to do right now because part of my brain has to register the locale of the tape dispenser, not to mention whether my husband put it back, does it need to be refilled, is on the grocery list...

Maybe later I can be great. Right now I am going under. I'll just the water hold me for a second.

My mother would ask us

"What is the most important thing?"

We knew that the correct answer was Time. [...]

Finding time is all we want to do.

Once you find time, you want more time.

And more time in between that time.

There can never be enough time.

And you can never hold on to it.

There can never be enough time. This knowledge of my death, the death of my children, the end of all of this that I love, is by far the heaviest, most unshakeable thing I hold. A task not unique to women, but collectively shouldered by all who are conscious.

Compliment Kalman's thought-provoking visual journey with a contemplation on how we view our mothers apart from ourselves, Zadie Smith on the necessity of creativity activity, author Joan Frank's self-authorization to be an author, Ursula Le Guin on the mad everywhereness of creative inspiration, and Hilary Mantel's tale of holding on - and letting go - of memory.