"Call off the search for 'wondrous' things and notice beauty hiding in plain sight. Wonder, it turns out, is not an inherent quality of things in the world but an attitude of mind."

It's a spider and web problem. The spiderweb is beautiful, the spider is scary. We learned this somewhere, somewhen. As we scampered out into the world with a mind of a child, kissed on the forehead by curiousity, we bungled up to the spider on its web and met a philosophical conundrum relative to our beholding it: One thing is beautiful, one thing is scary. Why, how do we know which is what?

Author Sophie Howarth (born in 1975) explains our early education: "Well-meaning adults stepped in to teach us what was safe to touch..."

At some point in all our lives, well-meaning adults stepped in to teach us what was safe to touch and what was not, what was nice to smell and what was not, what was good to eat and what was not, what belonged to us and what did not. So it was that we came to see spiderwebs as beautiful but spiders as scary, water as life-giving but rain as irritating, people as kind but strangers as dangerous, bodies as marvellous though we should not admire our own too much. We were educated in the ways of the world, but we lost a good deal of our natural curiosity in the process.

That is the moment we learned unwonder. The moment we forsake curiousty for certainty. Where did wonder go? Did it go? Or, as Howarth suggests in her Everyday Wonder: How to Find Beauty in the Ordinary, is wonder an internal ability rather than an external compunction? An ability waiting to be found and flexed?

Horwarth writes: "Call off the search for 'wondrous' things and notice beauty hiding in plain sight. Wonder, it turns out, is not an inherent quality of things in the world but an attitude of mind."

Instead of adding to the chorus of despair or turning away when it all feels too much, let's keep quietly turning towards the world, in its glory and its devastation. Let's savour the wind on our faces, the sun on our floorboards, the dew hang-ing from a branch or the sweat building on our brow. And let's resist the darkness by shining more light on the many small flickers of goodness and flashes of beauty. They are always there, waiting patiently for our attention.

It's a personality, not a geography issue. It is who you are, not where you are. The spider owes us no wonder. The exercises to flex this ability are simple and Howarth walks us through a few, including sensory check-in, putting objects in our near vision (i.e. getting closer to them), and my favorite "the secret life of things" which empathizes the object's POV at the expense of our own.

What is it like to be fruit on the hot pavement, looking back up at your maternal tree, sensing distance from her, sensing her fluid leaving your body as you desiccate? Would it be freedom or loss?

"Fallen Berries" Hackney, 2013.

"Fallen Berries" Hackney, 2013. An important part of Howard's strategy to help us use our wonder muscle is seeing familiar places anew. Like streets: a catchall for those things fallen and dropped, an endpoint for gravity's vectors, the tophat to metres of topsoil.

"Broken Glass," 2013.

"Broken Glass," 2013. And homes. Does it get more ordinary than home? These spaces catch and collect all the things that have meaning, memory, and things that hold our story. And yet we ignore them daily, treat them as nuisances or efficiencies. Time to remember, time to wonder.

Back to the spider and web problem. We can get around the spider's appalling creepiness (for me it's the eyes) if we imagine their sensory intake: how do we appear to them? How does the world? What is the precise thought that goes through their head before they let go and fly on the breeze? How does it feel to release a web? How do they know how to make webs? How do they know wasps hurt? Some entomologist knows the answers to this, of course, but do you? How did they get to those answers? How does knowledge even originate?

Wonder (I imagine Howarth saying warmly) wonder.

"Shinjuku," Tokyo, 2016.

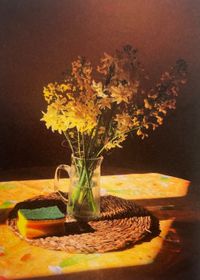

"Shinjuku," Tokyo, 2016. When Howarth writes about observing a bowl of fruit, I'm reminded of Cezanne, whose painting of light and shadow over a bowl of apples and peaches ushered in an entirely new way of seeing and thus, painting. If we abstract color and light from form and function, at some point color and light are all that remain. Abstract art owes its existence to Cezanne's wonderment.

"Coming To My Senses" 2024."

"Coming To My Senses" 2024." Why don't we wonder more? This beautiful, sumptuous feast of living? Because the habit of wonder costs time. Pausing to ingest the imperceptible syncopation of household objects makes us late for real-life demands.

"Howardian Hills, North Yorkshire" 2016.

"Howardian Hills, North Yorkshire" 2016. But there is a greater cost to being someone on whom nothing is lost. A huge cost, in fact. Taking time to notice and wonder at constellation-like potato patterns creates an emotional pull, a weight. A celebration of beauty and a knowledge that it's fleeting.

Like John Keats who sought his own beauty/death fusion, Horwarth calls this joy + sorrow, akin to having an open heart. She posits that an open heart, though vulnerable and affected, is more beneficial to the soul, the body, and the mind than the alternative numbness. It also helps the social fabric, the collective empathy of governing bodies, and the mandate we pass on to our kin, et cetera.

"Lesley" 2021.

"Lesley" 2021. We live in an era where truly great 'wonders' become a pixelated screen experience, visually nestled between celebrity news and cat videos. In short time a mountain, a canyon, and a black hole become irrelevant. It is no longer a spider and web problem, there are no spiders, and there are no webs.

Which is why Everyday Wonder is so critical. When we flex our wonder muscles, we can make everything significant. What an awesome power that is, to make things matter.

No one knew or at least

I didn’t know

they knew

what the thin disks

threaded here

on my shirt

might give me

in terms of joy

this is not something to be taken lightly

the gift

of buttoning one’s shirt

slowly

top to bottom

or bottom

to top or sometimes

the buttons

will be on the other

side and

I am a woman

that morning

slipping the glass

through its slot

I tread

differently that day

or some of it

anyway

my conversations

are different

and the car bomb slicing the air

and the people in it

for a quarter mile

and the honeybee’s

legs furred with pollen

mean another

thing to me

than on the other days

which too have

been drizzled in this

simplest of joys

in this world

of spaceships and subatomic

this and that

two maybe three

times a day

some days

I have the distinct pleasure

of slowly untethering

the one side

from the other

which is like unbuckling

a stack of vertebrae

with delicacy

for I must only use

the tips

of my fingers

with which I will

one day close

my mother’s eyes

this is as delicate

as we can be

in this life

practicing

like this

giving the raft of our hands

to the clumsy spider

and blowing soft until she

lifts her damp heft and

crawls off

we practice like this

pushing the seed into the earth

like this first

in the morning

then at night

we practice

sliding the bones home.

From Ross Gay's poem "Buttoning and Unbuttoning My Shirt" published in 2015.

Supplement this gorgeous guide with the memoirs of the invicted David Attenborough who just turned 99 and still adheres to a child-acquired characteristic: "It never occurred to me to be anything other than interested"; environmentalist Rachel Carson who originally described wonder as a sense to be tested and cherished and whose voice is echoed by anyone who wonders about wonder, and Pablo Neruda's sublime poetic love for the most trivial of things accompanied here by the everyday objects of ceramicist Honor Freeman.