"Fairy tales, on the other hand, are an abstraction... in which fantasy beings or archetypal images of the unconscious deal with one another."

We use fantasy to make sense of reality and extend it outside the limits of knowledge. The long history of monsters, creatures, and illusions that bridge what we know and what we see (my favourite is a creature in Japanese folklore that exists as an invisible wall which emerges when we feel tired and powerless.) And then there is Jorge Luis Borges's excellent bestiary of mythical creatures (which the author spent his life collecting and amending).

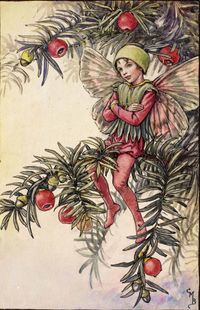

The Yew Fairy from Cicily Mary Barker's 1923 Flower Fairies, a poetic concoction of seasonal nature fairies.

The Yew Fairy from Cicily Mary Barker's 1923 Flower Fairies, a poetic concoction of seasonal nature fairies.Fairy tales and their inklings are a Western invention as a literary genre but have been passed on through voice around fires, tables, beds and in the domestic hearths of life across all peoples and eras. Each teller has cultivated fairy tales, each one a chef of the genre, a true example of craft (read more from Angela Carter on how fairy tales are like meatballs).

Fairy tales are accessible and relatable and beckon us to embellish and maintain them simultaneously—to retell a well-known story in our manner—an oral palimpsest. But could their continuity in human culture also be connected to their psychological immediacy? Could their narratives mirror our self-narratives in some abstract way?

A fairytale is "the dance of archetypes happening in the unconscious", writes Marie-Louise von Franz (January 4, 1915 – February 17, 1998), a pupil of Carl Jung and brilliant writer of Jungian psychology and the "shadow" in fairy tales. In one of her last books, The Cat: A Tale of Feminine Redemption, von Franz illustrated how these deceptively simple and even homely anecdotes function as the bearers of more profound expressions of self.

Fairy tales are an abstraction... That means you don't have a human ego encountering the world of the unconscious. You have fantasy stories in which fantasy beings or archetypal images of the unconscious deal with each other. That's one way to put it. In a saga, there is our world-light of consciousness and the hero, who goes somewhere and meets an archetype or several archetypes. In a saga there is always this going over the threshold and sometimes the fearful running back.

Jung's archetypes—models of how we exist and interpret our immediate world—were a significant component of his modern psychological theories. According to von Franz, these archetypes—the hero, the sage, the caregiver—are the foundations of fairy tales and are presented through the omniscient, agnostic narrator. That schematic figure allows us to connect to the tale.

Now in a fairy tale, you have a storyteller-that's an ego-who tells about the dance of archetypes happening in the unconscious. The hero in fairy tales is not a normal human being and has no human reaction. He is not frightened when he meets the dragon. He doesn't run away when a snake begins to talk to him. He doesn't get the jitters when the princess turns up at night by his bed and tortures him, or whatever happens. He is either intelligent or a Dummling- a stupid, dumb person. He's courageous, quick-witted or clever, or something of the kind in a very schematic way. And he just acts through the story-bang, bang, bang, according to his nature. If he is courageous, he fights everything. If he is witty, he always makes a trick out of everything. He has absolutely no psychology. He is a schematic figure. And if we look at him closely, we see a purely archetypal figure.

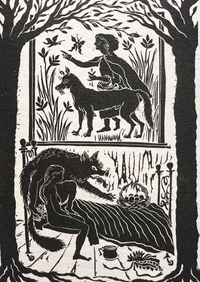

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood for Angela Harding's Book of Fairy Tales.

Woodcut print by Corinna Sargood for Angela Harding's Book of Fairy Tales.Given this empty space, we, the readers and the listeners of the tale enter the fairy tale and project ourselves onto the characters. Whether it is the princess, the witch, the hero, or the dragon (my own shorthand of characters does not do the genre justice), we find ourselves relating to the tale; it's deeply familiar. Von Franz continues:

Ultimately, of course, objectivity is only an approximation. We are bound to project our personality into a fairy tale; we see the things that appeal to us and overlook things that are not in our makeup. So even a so-called objective interpretation is far from completely objective, but at least one can fight those very primitive ways of projecting and make an attempt in that direction.

Terry Pratchett once argued for the necessary realness of fantasy. Von Franz would agree: this abstractness -—the utter unreality of the tale due to magic, creatures, or imagination—attracts us to the genre and invites us to participate. We see the same with ancient myths, such as Stephen Fry's reverent retelling of Greek myths with an eye towards modern hypocrisy or the demons of Japanese folklore imagined and drawn by Japan's first political caricaturist. Fairy tales are a unique, beautiful human invention.