"My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."

"We have to prevent it from being diluted so that it should be intolerable," Simone Weil wrote of suffering. Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön gently reminds us that fear can be a great undoing. Both writers make me think of Wilfred Owen.

One of the Great War poets, Wilfred Owen (March 18, 1893 – November 4, 1918), was instrumental in developing poetry as a truthful witness to atrocity and chronicle of horror rather than a means to buttress morale and feed patriotism. In response to Germany's slick propaganda efforts during the First World War, the British government began to amass a collection of writers and authors and nudge them to write material supporting the war effort. It was termed the British Propaganda Bureau or, more commonly, Wellington House. Members included G. K. Chesterton, Thomas Hardy, John Galsworthy, Arthur Conan Doyle, and H. G. Wells (although not all contributed.) It is against this Nationalistic fervor that Owen's poetry stands in brightest contrast.

George Orwell's poem was written when he was eleven and published under his real name, Eric Blair. The poem was posted on Oct 2, 1914, as a rallying cry for patriotism. © Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard.

George Orwell's poem was written when he was eleven and published under his real name, Eric Blair. The poem was posted on Oct 2, 1914, as a rallying cry for patriotism. © Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard.Owen's most famous line, "Poetry is in the pity," exemplified poetry's role in portraying war's horrors, inhumanity, and pathos. Owen's specific war poems contain his greatest verse, most written within a year when Owen was hospitalized in Edinburgh from shell shock - a PTSD common to soldiers fighting on the front line.

Like many British youths, Owen was called to serve in WWI, and, although terrified, he drew strength knowing he was perpetuating a grand fabric of English existence. He wrote to his mother:

Do you know what would hold me together on a battlefield? The sense that I was perpetuating the language in which Keats and the rest of them wrote!

Keats, who died almost exactly a century before Owen, would have found true, meaningful beauty in Owen's moral exactness. From his first-hand view, Owen observes and renders both intimate and landscape shots of the horrors of war, from the cramped and lonely trenches where wounds bleed off the page to attacking men who flock to glory at the cost of their own slaughter.

The Next War

Out there, we walked quite friendly up to Death,

Sat down and ate beside him, calm and bland,-

Pardoned his spilling mess-tins in our hand.

We've sniffed the green thick odour of his breath, -

Our eyes wept, but our courage didn't writhe.

He's spat at us with bullets, and he's coughed

Shrapnel. We chorused if he sang aloft,

We whistled while he shaved us with his scythe.

Oh, Death was never enemy of ours!

We laughed at him, we leagued with him, old chum.

No soldier's paid to kick against His powers.

We laughed, - knowing that better men would come,

And greater wars: when every fighter brags

He fights on Death, for lives; not men, for flags.

Wilfred Owen.

Wilfred Owen.Human consciousness on war is a significant theme of Wilfred's work, and he deals with it on many levels. Collective consciousness—do we know what it means to wage war? Individual consciousness—do we know what it means to march towards death and let him "shave us with his scythe"? And a form of hidden consciousness - What do we not yet see about war?

Owen's achingly beautiful and simple poem "Conscious" is a close-up of a dying soldier who slips from a hospital ward to a trench and, finally, to nothing.

Conscious

His eyes come open with a pull of will,

Helped by the yellow may-flowers by his head.

A blind cord drawls across the window sill. . .

How smooth the floor of the ward is! what a rug!

And who's that talking, somewhere out of sight?

Why are they laughing? What's inside that jug?

"Nurse! Doctor!" "Yes; all right, all right."

But sudden dusk bewilders all the air—

There seems no time to want a drink of water.

Nurse looks so far away. And everywhere

Music and roses burst through crimson slaughter.

He can’t remember where he saw blue sky.

Cold; cold; he's cold; and yet so hot:

And there's no light to see the voices by—

No time to dream, and ask—he knows not what.

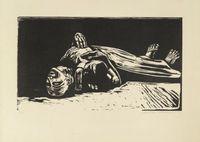

"The Widow II" (Die Witwe II) woodcut, 1922. Käthe Kollwitz was a German artist focused on the vulnerable members of society affected by traumas like WWI. Learn more. © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS)

"The Widow II" (Die Witwe II) woodcut, 1922. Käthe Kollwitz was a German artist focused on the vulnerable members of society affected by traumas like WWI. Learn more. © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS)Tragically—and it feels inevitable—Owens died on the battlefield in France at age twenty-five. He only saw five poems published. He was tremendously instrumental in changing the nature of poetry as a witness.

"I was indeed shocked with this sight; it almost overwhelmed me, and I went away with my heart most afflicted," wrote Daniel Defoe in his account of the great plague of 1665: he spoke explicitly of the mass graves which entombed plague victims. Defoe would have nodded silently at Owen's mournful verse.

Anthem for Doomed Youth

What passing-bells for those who die as cattle?

- Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, -

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Battle of the Somme, France. 1916.

Battle of the Somme, France. 1916.Apologia pro Poemate Meo

I, too, saw God through the mud, -

The mud that cracked on cheeks when wretches smiled.

War brought more glory to their eyes than blood,

And gave their laughs more glee than shakes a child,

[...]

I, too, have dropped off Fear -

Behind the barrage, dead as my platoon

And sailed my spirit surging light and clear

Past the entanglement where hopes lay strewn;

And witnessed exultation -

Faces that used to curse me, scowl for scowl,

Shine and lift up with passion of oblation,

Seraphic for an hour; though they were foul.

I have made fellowships -

Untold of happy lovers in old song.

For love is not the binding of fair lips

With the soft silk of eyes that look and long

Owen represents an entire generation of men sacrificed on the high altar to the whims of nations. His witnessing and compassionate poetry reflect the actual costs of war, lest we forget.

Many have played the role of witness over time, carrying this unrelenting burden. Some more intentionally than others. Elie Wiesel believed that witnesses must carry the past into the future, while George Orwell immersed himself in poverty to explore the injustices that he saw. When Toni Morrison wrote of bearing witness to Martin Luther King, Jr., she focused on shouldering his legacy (and falling woefully short.)